After a brief spell in the legal wilderness, it looks like the trusty old injunction is enjoying a moment in the sun again. A couple of big names have taken out gagging orders recently – but whatever happened to all those old ones from a few years back? Weren’t we supposed to tidy that all up?

Gagged And Rebound

Incredible though it may seem, it’s been nearly five years since superinjunction mania swept the nation.

Why, it seems like only yesterday that Ryan Giggs’ brother was chasing him around town with a claw-hammer in all the fall-out surrounding his prolific hushed-up shagging.

The memory of someone slipping a sex toy up the arse of your granny’s favourite actor is still green in our mind; and talk of Fred ‘The Shred’ Goodwin’s sexual shenanigans has only just stopped echoing around the House of Commons.

Can it really be half a decade since Giles Coren faced the threat of prison for joking about Gareth Barry? Or that Jemima Khan had to make a horrified public denial of a non-existent affair with Jeremy Clarkson?

Funny how time flies when your industry finds itself at the centre of multiple police investigations, criminal court proceedings and public inquiries, isn’t it?

History Repeating

Back in early 2011, it seemed that public opinion was really getting behind the idea that rich and famous men shouldn’t be able to take out a gagging order each and every time they get caught with their pants down.

Once the allegations of phone-hacking surfaced a little later in 2011 though, the national mood changed somewhat.

It was entirely right that the conversation surrounding the ethics of superinjunctions was put on hold while our focus switched to the investigations into alleged institutional criminality taking place on Fleet Street. But now that Lord Leveson has held his inquiry, News International has been up in the dock at the Old Bailey, and various guilty parties have served time inside, we have yet to pick up where we left off with the privacy injunction discussion.

If you think that Twitter had already blown that whole thing sky-high, then you’d better brace yourself. After social media went into overdrive trying to bust superinjunctions when the whole Giggs debacle kicked off, actually, not much has changed since then. Despite the internet’s best efforts, more than 50 of those old injunctions are still standing – and 2015 has seen the slow, steady return of more.

Now that the dust is starting to settle after a tumultuous few years in media land, the old wheels are beginning to turn once more. Red-tops are sniffing around footballers and unfaithful TV actors again. Kiss-n-tell girls are starting to see their way towards a Christmas bonus. And, as sure as night follows day, London’s top law firms are pressing their clients’ case under Article 8 of the Human Rights Act.

So where exactly do we stand now?

As the proud owners of an injunction that is still, stupidly, in force – we’ll tell you.

Terms And Conditions

The Human Rights Act of 1998 brought about the incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law, which lead to the development of modern privacy law here. Article 8 of that act sets out the right to a private home and family life, while Article 10 enshrines the right to free expression.

As you can probably work out, there’s a bit of a tension between those two principles. A tension that is frequently argued over by Britain’s robust and rambunctious tabloid press and London’s highly paid and ever-innovative legal brains every time somebody wants to take out an injunction.

Last time around the word ‘superinjunction’ got batted about without much thought or accuracy. It is a pretty sexy sounding name for what is otherwise a very tedious piece of paperwork, but ‘superinjunction’ actually refers to a something very specific – and the phrase is often misused.

So, to be absolutely clear what we’re talking about, briefly, these are the main types of injunction.

Standard Injunction: A court-issued legal order which permanently prevents private or otherwise sensitive information being made public. Usually they are taken out against a named individual or company – either the person threatening to leak the story (the spurned ex-lover; the disgruntled associate); or the publication which is planning to run it (Associated Newspapers; Mirror Group Newspapers etc).

There are occasions when you can take out an injunction against Persons Unknown – say, for example, when burglars steal a laptop with ‘sensitive information’ on it (a.k.a. sex pics) which may then get shopped around to publications.

Interim Injunction: Taking out an interim injunction is the first step in the injunction proceedings. It is, essentially, a sticky plaster – an immediate but (supposedly) temporary solution, applied for in an emergency and granted short-term to prevent publication of private information while the details of a case for a proper, permanent injunction are built.

These interim injunctions are circulated to newspapers and any other related publications to make sure that their editors and journalists are also aware that an injunction is in place so they don’t publish the story either. It can be reported that a person has taken out an injunction, but the content of that injunction is legally protected.

Anonymised Injunction: This is a type of interim injunction where the names of the individuals are switched out for a three-letter code (Zac Goldsmith had an anonymous injunction upon which the anonymity was abandoned, so we can tell you he used to go by the code ‘QRS’). As with a standard injunction you can still report that an injunction exists but, because there is no name to put to it, you have to resort to those classically vague “a man working in the entertainment industry” style of descriptors.

Superinjunction: This is where things start to get a little meta. A superinjunction is an injunction (usually anonymised, but not necessarily) which has an added bonus clause that prevents journalists and other publishers from reporting the existence of the injunction itself. It’s like a magician making a rabbit disappear, then making himself disappear.

Hyperinjunction: This one will have you gagged tighter than a Conservative MP in a motel bathroom on a bank holiday weekend. These sorts of injunctions are almost technically impossible to know about unless you apply for one yourself or are the judge granting it. The clauses of the injunction make it illegal to even mention it to a third party, journalists included. Sort of a superinjunction squared.

Though the superinjunction did become popular with the celebrity set, many of the most famous injunctions taken out in the Glory Years (2008-2011) were actually just toughly-worded anonymised injunctions.

Many of them weren’t even fully fledged injunctions either, just interim injunctions that were supposedly acting as placeholders while the applicants started official (read: expensive) proceedings, but never actually did.

And this is what sits at the heart of the problem. So few of these cases have been revisited by the applicants or defendants that they’re all just sort of sitting there.

We’re still bound by one – despite the story that the injunction concerns having been reported publicly a number of times across a number of different publications. Yet because of the deeply ramshackle nature of privacy law in this country, technically, we’ve been stopped from telling you this.

Even though you probably already know it.

WER v REW

In January 2009 we ran a story that clearly touched a nerve with someone as, the following day, we received a phone call from the infamous law firm Schillings telling us that their client had applied for an injunction, forbidding us from publishing anything further on the matter.

(As is traditional when lawyers want to throw their weight around a bit, Schillings decided to wait until late on Friday afternoon before placing that call; a favoured tactic of the more aggressive firms, so they can spoil as much of your weekend as possible.)

Consequently, on the following Monday afternoon we were pulled into court.

The full hearing is available to read and is a matter of public record. The case was WER v REW. We are REW and WER is the code that was given to Chris Hutcheson.

If the name doesn’t ring a bell, Chris Hutcheson was the CEO of Gordon Ramsay’s company Ramsay Holdings Ltd. He also just happened to be Gordon Ramsay’s father-in-law – the father of Gordon’s wife, Tana Ramsay.

The reason Chris Hutcheson was of interest was because he had a secret second family (he still does, of course – though they’re no longer secret). He had been keeping a mistress with whom he had two children, and his first family – Tana’s lot – had no idea.

Now, it might be worth pointing out that at this juncture that this is not a cost-free exercise. Injunctions are not cheap – not for the appellant, not for the defendant. Even though we hadn’t done anything illegal and even though we hadn’t said anything defamatory we had to go to court. And to turn up to court with proper legal representation costs money.

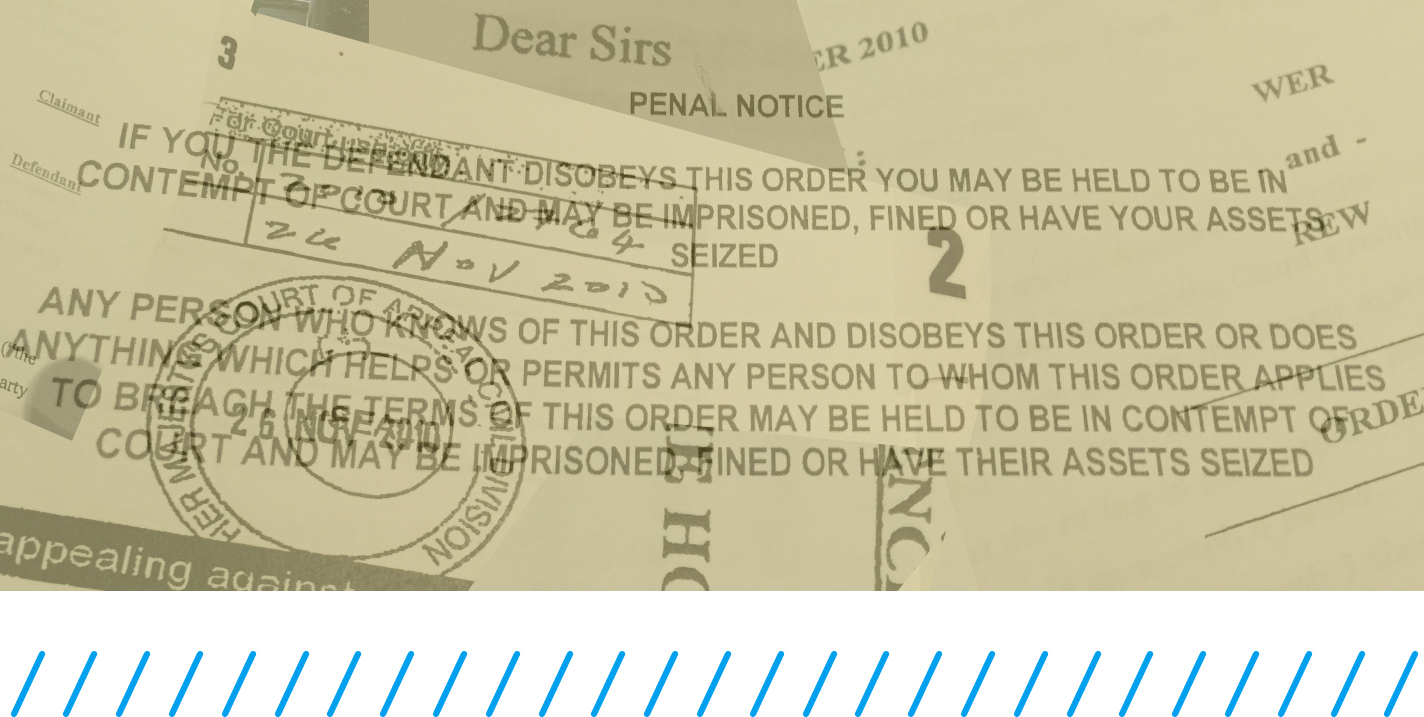

If you get the most junior of lawyers to represent you, already you are looking at a couple of grand minimum. But when you only get a few hours to set out your whole case, an interim injunction is not the easiest thing to successfully defend. The documents that land on your desk threaten imprisonment, fines and the seizing of assets, so you want to make absolutely certain you aren’t putting a foot wrong. Especially if you’re going up against muti-millionaires.

Responding sensibly and responsibly to the issuing of one of these injunctions can therefore push your costs up into the five-figure bracket. Costs like that can be fairly easily absorbed by a national newsgroup, but to an independent publisher it’s a fair bit of cash. Just to be told you can’t run a story you know for a fact to be true.

Hutcheson was granted his injunction, which prevented us (and everyone else that his legal team had requested it be sent out to – which was every national daily and Sunday paper, plus other selected media outlets) from reporting the story.

The only reason we can tell you about this now is that – thanks to Ramsay family and company politics – the full story ended up winging its way to the Sun newspaper in 2011 (a couple of years later) and they applied to the court to overturn the injunction.

When the Sun brought this to court, the judge first awarded Hutcheson another injunction and another set of initials (KGM v News Group Newspapers) but then quickly overturned it and awarded in favour of the newspaper, who were free to publish the story.

In 2011 it was agreed that Hutcheson had no legal right to an anonymised injunction, preventing the story from being discussed. The story came out and the fall-out was extremely far-reaching.

One of the many and varied legal tussles between Gordon Ramsay and Chris Hutcheson in the years that followed involved allegations that Hutcheson was also taking money from the company for his own personal use. There were claims that he had “systematically defrauded” Gordon Ramsay’s company to the tune of £1.5 million, money he had allegedly been using to fund his secret second lifestyle.

Suddenly it’s not just a case of one man’s private indiscretions. It’s a case of alleged serious financial misconduct.

The weird thing is, we are still technically bound by the injunction WER v REW. Even though it is known Chris Hutcheson has two different families – because it was reported in the Sun, the Daily Mail, the Telegraph and others – our original injunction still hasn’t been overturned.

The only thing that changed for us was that it could be reported that WER and REW were Hutcheson and Popbitch (Popdog Ltd).

And, in a nice little twist of the blade, after having had to pay a five-figure sum just for the privilege of being injuncted, if we ever do want it overturned, the onus is on us to arrange that with the courts. And pay for it.

Why bring any of this up now? Because injunctions have been making a bit of a comeback.

Truce And Lies

For some years virtually no-one was applying for injunctions, nor was anyone granting them. The Giggs case had had a bit of a scorched earth effect. That particular strain of business had dried up almost completely for most law firms and, as the poster boys for privacy, Schillings’ future looked pretty rocky until it pretty much got rid of everyone involved in the superinjunction business and fairly successfully turned itself into a wide-ranging reputation management firm.

But this year, we’ve noticed a few interesting injunctions being awarded again. Essentially there’s been about a three year truce in the world of celebrity-tabloid injunction interactions – but only a truce. Not lasting peace. Shots are being fired again from both sides to see where the public and the court’s opinion lies.

The tabloids opened up with a couple of PG rated exposés: Yaya Toure making late-night visits to a “mystery brunette”; Luke Shaw sexting someone – neither of which really merited much in the way of court action.

But then in August – wham! – the anonymised injunction was back: ”A prominent sports star wins injunction gagging revelations about him cheating on his wife-to-be with female celebrity.”

Unlike Giggs’ attempt, this time the injunction has held. But the press doesn’t appear to be taking the threats as seriously. It doesn’t take a sleuth to join the dots between the media stories and the internet chatter to figure out who the two people are.

Also casting a chill around the VIP bars of exclusive nightspots is the fact that famous men with a wandering cock haven’t had it all their own way in their courts this time out, even with their millions of pounds behind them.

Manchester United footballer Marcus Rojo had his attempt at a gagging order rebutted in the High Court in April. His legal team had accused the woman he’d been shagging of trying to blackmail him (a tried and trusted tactic from the Golden Years which seemed to work without fail back then, even though there was little or no evidence to support their case.)

This time though it was thrown out by the judge who said that, far from being a blackmail case, the footballer’s representatives had been the ones trying to buy his mistress’s silence.

But let’s not forget that the interim injunctions on file aren’t always just a case of salacious footballer kiss-n-tells, or actors getting pegged off prostitutes. Some of the injunctions still effectively in force cover up some pretty inglorious stuff that the courts have no real reason to keep quiet.

For example, the injunction ETK v News Group Newspapers Ltd. Their names have been published in the press elsewhere in the world, but still – by letter of the law – no-one is supposed to mention the names of the two people (one male, one female) who are wrapped up in this case.

The basic details are that the two stars had an off-screen affair which ended when the male actor’s wife found out about it. The male actor then used his not-insignificant influence with the producers to have his female co-star kicked off the show (or, as the documents put it, “the appellant told them that he would prefer in an ideal world not to have to see her at all and that one or other should leave” – which, given that he was the star of the show and she only joined in a much later series, was only ever going to end one way).

Sure enough, she was promptly let go. And no-one can report her side of this story because he took out an injunction to stop all of this from coming out.

The stupidest part of the whole thing is that the names have been reported elsewhere in the world. The injunction only holds for the British courts so the story is out there – not least in the female co-star’s home country. Anyone can find out the names with three clicks of a mouse and yet the press is still forbidden, by law, to mention them by name because he has used some of his multi-million net worth to take out an anonymised interim injunction. One that just keeps on rolling in perpetuity until a newspaper pays to tackle it, or the courts finally re-evaluate these cases.

Injunctions undoubtedly have a place. People get blackmailed. Personal property gets stolen. Paparazzi take intrusive photos of people where they have a reasonable expectation of privacy. There is information that could be seriously damaging to individuals were it to be published – and the British press doesn’t exactly have an entirely glowing track record when it comes to responsible reporting.

We are not saying that injunctions shouldn’t exist, but the privacy law that effectively came into force in the late noughties has never been properly appraised.

Until it is, those interim injunctions, which were granted to give both sides (and the courts) time to work out what should and should not be reported, are still just sitting there. A blanket ban on anything in those 50+ cases, including all the stuff that should be properly reportable.

Sure, a few committees have talked a good talk, and put out a paper that sounds good in theory. Everyone loves to voice the fact they believe in open justice, but there’s been very little appetite to re-fight these battles from either the press, the lawyers or the philanderers.

And, really, what reason do they have?

Well, here’s one.

Part of the Tory policy at the last election was to unshackle Britain from the European Human Rights Convention. If the hard right of the party gets their wish and the Human Rights Act 1998 is scrapped then it’s possible that could spell serious trouble for those wanting the protection of the courts.

Because no Human Rights Act means no Article 8.

And no Article 8 means no enshrined right to a private life.

So maybe they want to start thinking about getting their affairs in order, and get the finer details of these cases hammered out while the going’s still good. Because there’s no telling what might happen next.

It’s not as if the anti-Europe Murdoch and Associated Papers have anything to gain from getting rid of Article 8 now, have they…?