Injunctions! What are they good for? Absolutely nothing – and this latest David Beckham fiasco has gone and proved the point once again. Highlighting yet more problems with the legal system as it stands, this is what happened…

Contend It Like Beckham

The news that David Beckham had taken out an injunction in order to stop his cunt-laden emails from leaking out to the press surprised us a little.

Not because it would have been a surprise to discover that a footballer had taken out an injunction. Footballers are second only to TV presenters in their haste to rush for an injunction whenever news of their indiscretions is due to hit the papers. It’s a tactic as common as four-four-two.

No, it was a surprise to us because David Beckham didn’t actually take out an injunction.

The injunction in question was taken out by a company called Doyen Global. And while it’s true that Doyen Global do Beckham’s PR – and Beckham may well have directly applied some pressure to keep stories of his four-lettered rants out of the press (there is an unidentified individual, XY, mentioned in the order) – the crucial fact remains: this isn’t David Beckham’s injunction.

Once again, for the sake of an attention-grabbing headline, the finer details of this story have been muddled. But there is something critical in the nitty gritty here and it risks being overlooked. Specifically, that injunction law has found yet another way to undermine itself.

We have spoken loudly and at length about the stupidity of injunction law as it currently stands and why we feel it is unfit for purpose. This latest example has shown further reasons why the whole thing needs urgent reform.

These are the problems.

1/ Geography

One of the big failings of injunctions that is constantly aired is that they are only enforceable in England and Wales. The courts hold no power over Scotland, no power over Northern Ireland and certainly no power anywhere else around the world – so if you are a globally recognised star (like David Beckham) or a globally focused company (like Doyen Global) it is extremely difficult for you to stop reporting in any other jurisdiction.

That’s not to say that taking an injunction out in England and Wales can’t still have some effect. The PJS olive oil celebrity sex party injunction is only applicable here in England and Wales – a ruling which has been upheld by the Supreme Court – and that story hasn’t made the papers yet.

(At least not in any official capacity.)

The trouble with this Doyen Global injunction is that it pertains to a huge email hack of their parent company, Doyen Sports. Doyen Sports is owned by Portuguese and Kazakh businessmen and is based out of Malta. Already, this gives it a wide international scope – but it widens out yet further as the real story that the hackers are trying to get to the bottom of involves the shady practice of Third-Party Ownership deals in international football trades.

To put all the moral and ethical arguments of email hacking and TPO dealing aside for now (they’re far too unwieldy to unpick properly here), this is not a story that stops and starts with David Beckham and the Honours List. That was just a side dish. The wider story involves a huge cast of international characters, so the reporting on it is going to be of interest to many different countries.

As a result, the cache of hacked emails at the heart of it is in the hands of publications all over Europe.

Regardless of where you stand on this particular issue, it is plain to see that an injunction in England and Wales is wildly insufficient in the fight to stop international information from leaking out into the public domain.

Making matters worse, because of the wording of the injunction, it didn’t even manage to cover the entirety of the English and Welsh press. It only effectively managed to cover a single publication – the Sunday Times.

2/ Direction

For the most part, injunctions are taken out against one particular publisher (in this case, Doyen Global took theirs out against Times Newspapers Ltd).

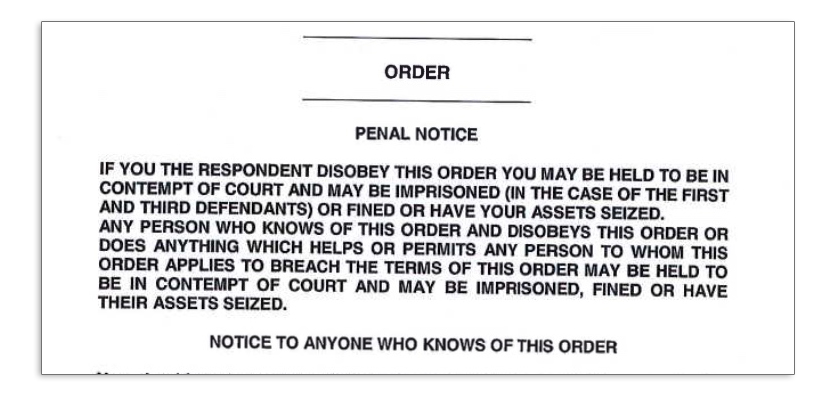

What usually happens is that notice of the injunction is then circulated to other publications, which automatically get caught up in the order too. This is the wording they use.

There’s a problem though. Further down the document there is a section of the order which, when taken in conjunction with the geographical limitations of the injunction, renders the entire process pointless.

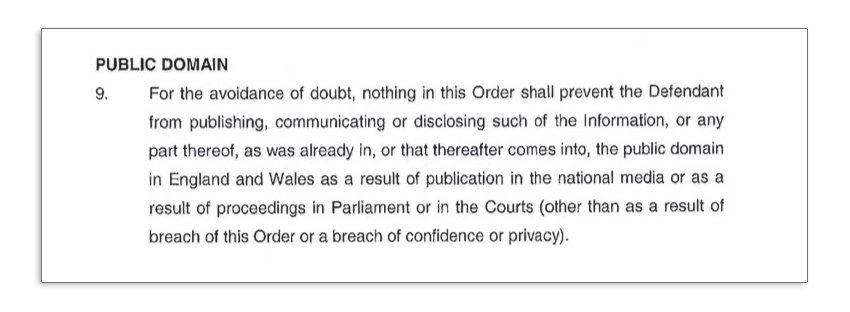

Section Nine of the order says that the injunction doesn’t stretch so far as to ban reporting on any information that happens to come into the public domain – even after the injunction has been issued.

Here it is in its original legal wording:

The bind it puts publications in is this:

1/ The injunction forbids them from reporting on the information contained within the order

2/ The injunction allows them to report upon things which find their way into the public domain

What happens when that information is one and the same?

If internationally recognised publications, which are freely available in the UK (like Der Spiegel for instance), have written stories on the hacked emails – is it now fair game? Or is it still covered by the court order?

As the Sunday Times is specifically singled out and named in the injunction, any attempt it might have made to publish a second-hand report would probably be seen as deliberate aggravation. But anyone else who is prepared to be a little more elastic with the interpretations of the order can mount a more robust defence about ignoring the bold, all-caps warning on the injunction’s front page in favour of Section Nine.

And you’ll never guess what went and happened…

3/ Team Work

Normally when an injunction is taken out against one of their own, the entire newspaper industry will rally round to try to help aggravate the injunction to within a hair of breaching the law. You saw it most recently when the Daily Mail started writing huge front page stories on the PJS v News Group Newspapers injunction, but it was happening constantly in the great superinjunction craze of 2011.

That’s just what happens. Nothing brings journos together like news of an injunction. There’s not much that can be done about that.

If you take out an injunction against one of Rupert Murdoch’s publishing companies though (say, for example, Times Newspapers Ltd) then you risk mobilising a much bigger machine.

Murdoch owns newspapers and magazines and TV channels and websites all over the world – hundreds of them – a sizeable majority of which are not bound by the British courts.

Try to muzzle one of his mouthpieces and… well, to get a little speculative for as second: is it merely coincidence that the Sun ran a huge front page splash about the fact Beckham called Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs and bunch of cunts the very same day that the Sunday Times was writing about an A-list celebrity who has taken out an injunction against them?

4/ Scope

Now that a judge has ruled enough of the Beckham information is public that the injunction no longer holds, Doyen faces another problem.

The injunction, when it still held, banned people from publishing any information “…contained in or derived from documents obtained from the email accounts of the Claimant’s employees, or from documents which the Defendant knows or believes form port of the Claimant’s document databases…”

Now at this point we can only guess, but if the juiciest thing to be found in a huge cache of hacked emails obtained as part of an investigation into dodgy dealings in the trade of international football players really was that David Beckham once threw a shitfit about not getting a knighthood – then they should be fine.

If, however, there is something a little more sensitive contained within these stolen documents then this injunction no longer protects anyone from its publication.

Again, you can argue the merits of whether or not this sort of case deserves to be injuncted or if information like is of vital public importance and needs to be reported on wherever its found. That’s fine. The fact remains though that the injunction system we currently have in place doesn’t help anyone.

Either the information should be injuncted – in which case, it shouldn’t be so easy to overturn the whole thing on such a trivial loophole; or the information shouldn’t be injuncted – in which case private companies shouldn’t be trying to weaponise the courts and threatening journalists with prison for reporting on factual evidence.

Whatever your personal opinion on the case at hand, current injunction law facilitates neither of those options.

5/ Cost

This isn’t just an academic exercise. A fun bit of chin-stroking for legal bods to engage in for the sport of it. This is the law of the land. This is an industry’s paid profession. Actual sums of money change hands for this sort of half-arsed service.

They’re not insignificant costs either. £60,000 is what the courts claimed it cost them to process this ruling; a ruling that collapsed quicker than Ronaldo when challenged. And that’s before you start getting into the lawyer’s fees on either side too.

All in, this has probably cost Doyen somewhere in the region of £150,000 to defend. And for what? If they weren’t fussed about the story leaking, they could have easily mishandled this story themselves for free.

Still, Beckham’s tax-dodged thousands need to be spent on something we suppose. Now that his football academies have closed, and his charity work is probably going to tail off now that the knighthood seems unlikely, perhaps this is where Beckham finally makes a lasting legacy for himself?

He’s already got a tax-dodging law named after him; maybe he’ll get a privacy law named after him too?