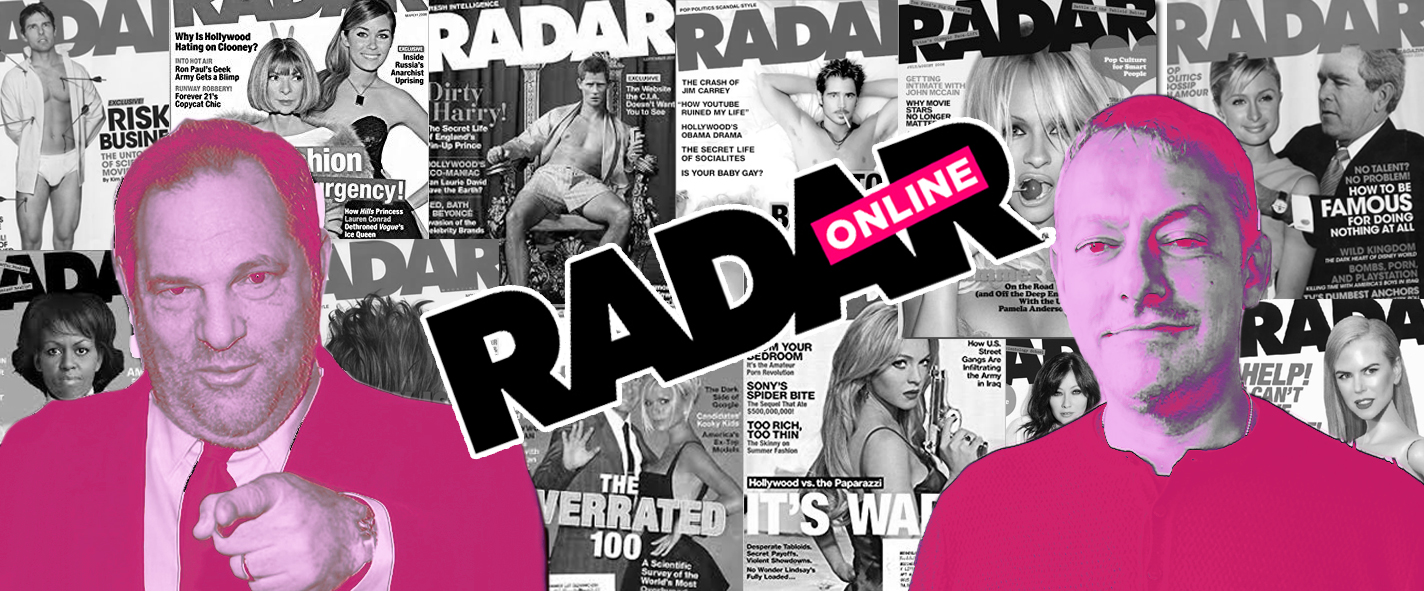

When a huge wave of allegations against Harvey Weinstein hit the headlines in 2017, reports quickly followed about the secret network of journalists and editors he had working for him in the shadows, helping to suppress negative stories. How did Harvey go about getting his gruff, sticky fingers into the print media pie in the first place? It’s a pretty interesting story…

I/ Talk Of The Town

If there was one silver lining to 9/11, it’s that it did help to thwart Harvey Weinstein’s ambitions to break into print.

Having first built a name for himself producing critically lauded, Oscar-nominated movies like My Left Foot and Sex, Lies And Videotape; before moving on to produce critically lauded, Oscar-winning movies like The Crying Game and The English Patient – Harvey Weinstein decided that 1998 would be the year he used his momentum (and money) to start expanding his interests.

The era of Harvey Weinstein: Movie Maker was drawing to a close.

The era of Harvey Weinstein: Media Mogul was dawning.

Along with his business partner/brother, Bob, the Weinsteins unveiled a new wing to the Miramax company in the summer of ’98. One that was set up to publish books, screenplays and magazines: Talk Media.

To lend this new venture a bit of credibility, they roped in two other big-name associates to join them. One was editor extraordinaire, Tina Brown (poached from the New Yorker; formerly of Tatler and Vanity Fair). The other was Condé Nast executive, Ron Galotti (whose previous credits included Vogue, GQ and being the real-life inspiration behind Mr Big from Sex And The City).

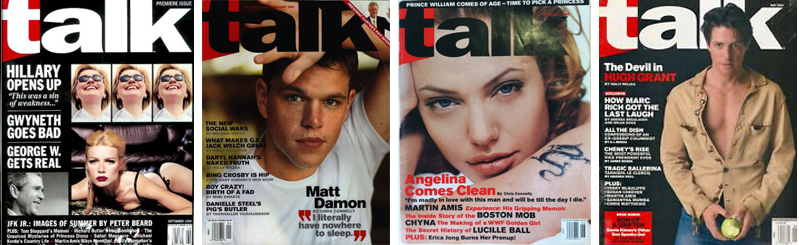

For a year, the four of them worked on creating a magazine that would become Talk Media’s flagship publication – the imaginatively titled Talk.

Billed as a fresh new voice to lead the cultural conversation into the next millennium; a breeding ground for the smartest talent in modern journalism; a true insiders’ bible, offering intimate access to the world’s most desirable stars, Talk debuted in September 1999 with a wildly extravagant launch party.

Henry Kissinger, Madonna, Salman Rushdie, Kate Moss were among the 1,000 strong guest list toasting to its first issue. Yet the whole thing would fold within two and a half years. Why? Because far from being the exciting blend of politics and pop culture that was promised, all it actually delivered was a middlebrow exercise in industry logrolling.

A cursory look through the covers makes clear just how often Talk was filled with stars who had recently appeared in a Weinstein-produced or Miramax-distributed movie.

– Gwyneth Paltrow (Shakespeare In Love, 1998)

– Matt Damon (Good Will Hunting, 1997; All The Pretty Horses, 2000)

– Angelina Jolie (Playing By Heart, 1998),

– Hugh Grant (The Englishman Who Went Up A Hill…, 2000)

– Sean Penn (She’s So Lovely, 1997)

– Heather Graham (Committed, 2000)

– Ben Affleck (Good Will Hunting, 1997; Shakespeare In Love, 1998)

– Gwyenth Paltrow, again (Bounce, 2000)

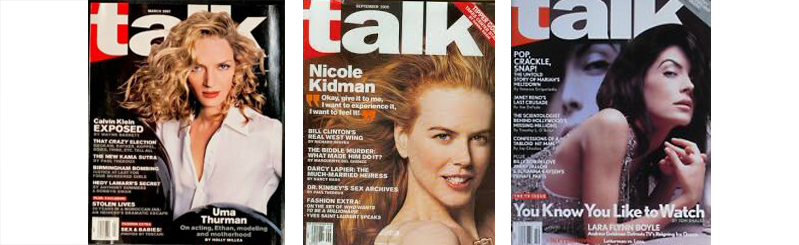

– Uma Thurman (Pulp Fiction, 1996; Vatel, 2000)

– Nicole Kidman (Birthday Girl, 1999; The Hours, 2001; The Others, 2001)

– Lara Flynn Boyle (Since You’ve Been Gone, 1998)

Talk wasn’t just a showcase for Weinstein’s movie interests however. It was also a pretty ripe payday for many of his other friends too.

The first issue went big on essay from Tom Stoppard (whose film Shakespeare In Love won Weinstein a Best Picture Oscar earlier in the year).

Another regular Talk contributor was the novelist Martin Amis (a former lover of Tina’s) who, by some crazy coincidence, had just signed a million-dollar deal to publish three new books through Talk Miramax Books.

Talk came in handy for greasing political wheels when such greasing was necessary. Rudy Giuliani, who was Mayor Of New York at the time, had been paid a $3 million advance for his memoirs by Talk Miramax Books – and got himself a lovely Talk magazine cover into the bargain as well.

And, of course, the proprietors would be terribly remiss if they didn’t use their magazine to run flattering features on their society pals. Like an essay by a 21 year old Chelsea Clinton in November 2001. Or this double-page spread photoshoot from 2000 where Melania Knauss (as she was then) dressed in a bikini, sprawled herself across the carpet of the Oval Office, writhing on the Seal Of The President, answering questions about how she imagined life as the First Lady would be.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, no-one seemed to be hugely interested in reading this type of chummy, elitist tugfest – so Talk published its final issue in February 2002.

Tina Brown blamed 9/11 for the closure, saying that the advertising recession September 11th had prompted had hit them hard, leaving the whole project $27 million in the red. In truth though, Talk had been in trouble long before that. Its ad sales had been floundering since the spring of 2000 and the magazine had somehow managed to blitz through an estimated $50m in its short life.

This failure didn’t seem to dull Harvey Weinstein’s lust for the magazine business. He was determined to stay involved in the industry somehow, so he tried to find another way to do it.

Eventually he would end up helping finance another new venture with one of Talk‘s top talents. But not before he tried to secure an alternate source of funding for Talk. Something he did by approaching a publisher which had actually been gravely affected by the terror attacks of September 2001.

American Media, Inc.

Hack Attack

On September 18th, exactly one week after the Twin Towers collapsed, somebody in Princeton, New Jersey, popped five letters into a postbox addressed to the headquarters of ABC News, CBS News, NBC News, the New York Post and American Media, Inc.

Enclosed in each envelope was a letter that read

09-11-01

THIS IS NEXT

TAKE PENACILIN NOW

DEATH TO AMERICA

DEATH TO ISRAEL

ALLAH IS GREAT

Also enclosed was a dose of anthrax.

Initially written off as ‘loony letters’ – the type that newsrooms receive every single day – they were tossed in the bin without much thought. But two weeks later, two members of AMI staff (mailroom chief Ernesto Blanco and photo editor Robert Stevens) were admitted to hospital showing signs of mystery illness.

At first Stevens assumed he must have picked up a nasty bout of flu from a recent trip to North Carolina and attributed the copious vomiting to that. The medics who assessed him at A&E briefly suspected he might have meningitis. However, it soon became clear he had inhaled anthrax and was succumbing to his sickness.

Four days later, Stevens was dead.

Up until that point, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention had recommended that AMI’s staff continue working at their office as normal. When they confirmed that anthrax spores had also been found in the nasal passage of Ernesto Blanco though, they gave immediate evacuation orders.

350 staff were taken outside and lined up to be tested for anthrax exposure while AMI’s headquarters were shuttered, sealed and quarantined behind them.

Such a swift evacuation from the building meant there had been no time to salvage anything. Not the computers. Not the office furniture. And certainly not the company’s extensive fifty-year archive of issues, photos and notes. There was no telling what might have been infected by the anthrax spores, so everything had to be abandoned.

An estimated 50,000,000 photos. Notes and files for thousands upon thousands of issues. All of it. It had all been lost to the attack.

Never one to drag his heels, the company’s CEO and President, David Pecker, had no choice but to relocate his entire operation and effectively start from scratch.

By Pecker’s estimates, he reckons the company spent $10,000,000 in response to that anthrax attack and lost another $15,000,000 in real estate by selling the contaminated office for just $40,000 years later.

So when Harvey Weinstein approached AMI with the prospect of taking on his limping vanity rag – a magazine that was already in the hole for $27,000,000, just for being shit – bailing him out was not hugely high on Pecker’s list of priorities.

Which isn’t to say that Pecker wasn’t interested in doing any business with Weinstein. Quite the opposite, in fact. They already had a fabulously fruitful relationship.

Not only was Harvey a regular source of stories for AMI’s tabloids, around this same time, Talk Miramax Books had agreed to publish a coffee table photobook of the National Enquirer‘s favourite photo stories, entitled Thirty Years Of Unforgettable Images (November 2001). Iain Calder, the Enquirer‘s editor at that point had also signed his own deal with Talk Miramax for his memoir, The Untold Story: My 20 Years Running the National Enquirer (July 2004).

So it wasn’t that Pecker and Weinstein didn’t have shared media interests. It’s just that Talk Magazine wasn’t one of them.

Rebuffed but undeterred, Weinstein began looking around for new opportunities instead – and quickly found one, in the shape of Maer Roshan.

Roshan Collusion

In the origin story of the National Enquirer, the relatively normal founder-editor character around whom all the properly mad stuff revolves was a guy called Generoso Pope, Jr.

Generoso – or Gene to his friends – was often described as having print ink running through his veins. A natural at the job, he was a workaholic who had a flare for finding good stories, born with great journalistic instincts and an intuitive understanding of what the public wanted to buy.

He started the Enquirer in 1952 with little more than the piss in his bladder after he was written out of his family’s will, but through a combination of hard work, steely determination and weekly cheques from some extremely seedy investors, he managed to make it work.

It wasn’t always easy going. In fact, a lot the money that propped the National Enquirer up in its early days came from Frank Costello, head of the New York Mafia – and Costello’s interest in the magazine didn’t come from a place of personal enthusiasm. For Costello, this was strictly business.

The fallout from Mafia deals can often generate a lot what is known in the magazine trade as “human interest”, so Costello was keen to secure some control over a publication on the newsstands. One that he could trust to turn a blind eye to some of his more sensitive business operations.

Costello was more than happy to stump up a weekly envelope in exchange for the peace of mind that comes from knowing he wouldn’t be reading reports in the Enquirer about bodies being dragged from the Hudson River, or unidentified drivers who had lost control of their vehicles in the darkened woodlands upstate.

Gene Pope, unwilling to displease the head of the Five Families and incur the wrath of the Mob, was happy to go along with that request. Sometimes, that was just the sort of deal you had to strike in order to get your magazine made.

–

In the origin story of Radar, this same role of ‘Founder-Editor Character Around Whom All The Properly Mad Stuff Revolves’ is played by a man named Maer Roshan.

Much like Gene Pope Jr, Maer is a natural born publisher. His impressive CV boasts a long list of titles he has been in charge of creating, launching or editing over the years. He created and launched QW, Tribe and The Fix; he worked as a deputy editor on New York Magazine; he edited FourTwoNine and, earlier this year, was appointed Editor In Chief of Los Angeles Magazine to great fanfare.

But the title that Maer is most closely associated with is Radar, even though he no longer has anything to do with it. He created it, launched it and saw it through three different print iterations over a very bumpy five years in which he tried valiantly to keep it afloat. Eventually though, he couldn’t make it work. It collapsed completely and its corpse was picked over by the beast that is American Media, Inc – where it now lives, in the hands of David Pecker.

Maer enters this story properly in 2001, when Tina Brown invited him to leave his post at New York Magazine to come and act as her second-in-command at Talk as Editorial Director.

As we now know, this job offer turned out to be a bit of a hospital pass as the magazine would no longer exist within a year. But rather than return to a salaried gig when it all went south, Maer decided that he would try something of his own instead.

Calling upon some of the colleagues he’d liked at Talk, and roping in a few from his New York days, Maer came up with the idea for a new magazine: Radar.

The idea was that it would cover much the same sort of scene as Talk had tried to, but the elevator pitch differed in one major respect. Radar would be cheeky.

It wouldn’t venerate celebrities as if they were inherently fascinating individuals. If it came across a star who was vapid, or venal, or vain then Radar wouldn’t shy away from making that the story – rather than just filling the page with some airbrushed puffery to keep the publicists happy.

That was the plan at least, but Maer didn’t have anything like the sort of money required to make a magazine like that. He knew a man who did though.

His old boss. Harvey Weinstein.

Talk Back

Maer Roshan’s reasons for taking Harvey Weinstein’s money are easy enough to see. He wanted to run a magazine, so needed money and access. Weinstein could provide both. The pair had previously worked together pretty harmoniously at Talk, so for Maer it was a no-brainer. If Weinstein was happy to continue bankrolling him at a new publication, one of his own direction, this was effectively a huge promotion for him. Why not try it?

What was less easy to see (at the time, at least) was Weinstein’s reasons for staying in magazines.

Not only had he already lost a huge chunk of cash taking his first steps into print media, Maer’s stated intent was to make a magazine that was a thorn in the side of celebrity. Something irreverent and snarky. Radar wasn’t going to be the Weinstein Variety Hour, the way that Talk was. Harvey’s stars wouldn’t be treated to the type of toothless Q&A his own magazine had so regularly run. If anything, the celebrities of his stable would now be some of the most obvious targets that Radar would train its sights on.

So why would Weinstein ever look to fund something like that?

For exactly the same reason that Frank Costello funded the National Enquirer. He wanted to control which stories came out and which stories stayed buried.

Let’s take a look at what we’ve learned since the dam of allegations against Harvey Weinstein broke.

In 2017, shortly after dozens of of women first came forward with stories of abuse at the hands of Weinstein, the New Yorker reported that Weinstein had been employing the services of shadowy private investigators to monitor these women – as well as the journalists who were following up on their leads.

Rose McGowan (who accuses Harvey Weinstein of having raped her) was one of the women he had surveilled. McGowan wasn’t just tailed by operatives from Black Cube, safely sat in blacked-out BMWs parked across the street. They actually embedded themselves within her daily life.

One Black Cube agent went so far as to use a false identity (‘Diana Filip’) to approach and befriend her, encouraging McGowan to join an elaborately fabricated women’s rights advocacy group as a ploy to meet with her no fewer than four times so that she could record their conversations and then feed that information back to Weinstein.

Now, technically speaking, we should be a little careful in saying that Harvey Weinstein engaged the services of Black Cube, because the person who signed the contract with them wasn’t actually Weinstein. It was Weinstein’s loyal, long-time lawyer, David Boies. Who – by some jaw-dropping, million-to-one miracle – was another of the people who signed a nice, juicy publishing contract with Talk Miramax Books for his book Courting Justice (acquired in 2001; published in 2004).

Fancy that!

Another detail from that New Yorker report was evidence that Weinstein had been secretly conversing with an editor at American Media, Inc. getting them to hand over any material that AMI reporters could gather on McGowan to attempt to discredit her allegations.

This is the same American Media, Inc. that Weinstein signed to Talk Miramax Books at the turn of the century. The same American Media, Inc. he’d tried foist Talk on after 9/11. The same American Media, Inc. that would eventually buy Radar in 2008 when Maer Roshan washed his hands of it.

This secret agent at AMI was the company’s Chief Content Officer, Dylan Howard. If the name sounds familiar, you’re probably remembering him from a story earlier this year, in which he got busted trying to blackmail Amazon boss Jeff Bezos with a set of dick pics that had come into his possession.

Though he’s been quietly sidelined from a lot of his day-to-day duties since then, Dylan Howard still officially holds a number of the job titles he did when he was working in concert with Harvey Weinstein.

Including Editor-In-Chief of the National Enquirer.

And – after Maer Roshan was no longer in the picture – Editor-In-Chief of Radar.

The Cheat Goes On

The Cheat Goes On

Hiring ex-Mossad operatives to spy on his victims does, admittedly, mark something of an escalation in his tactics – but, generally speaking, this sort of behaviour didn’t start in 2017. Weinstein used his influence in the world of print media to attempt to influence the suppression of these types of stories for decades now.

For example, in 2003, rumours started circulating around Hollywood that Weinstein was having an affair on his first wife (Eve Chilton) with the woman who would later became his second (Georgina Chapman). Naturally, a story like that could cause a gentleman great embarrassment – so Weinstein was keen to keep it on the down-low.

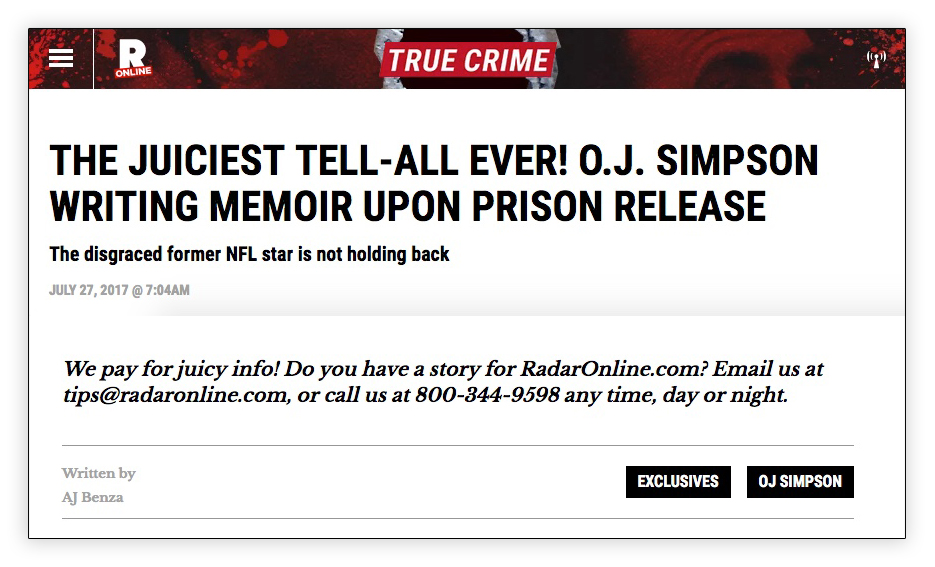

How did he manage to do that in a city that’s crammed full of gossips? By hiring a gossip writer himself, AJ Benza, and keeping him on a monthly retainer to dig up stories about other celebrities and pass them across to Weinstein, so that if journalists ever called Miramax looking to investigate the rumours they’d heard about Harvey having an affair his PR team was well stocked with plenty of juicy celebrity stories they could offer in exchange.

And where did he discover this AJ Benza character? You may find this hard to believe – it really is the darnedest thing – but Benza also happens to be another writer who managed to snag himself a book deal in the early days of Talk Miramax Books (Fame: Ain’t It A Bitch, May 2001; later optioned by Miramax for a film adaptation).

Benza’s bespoke services were courted by Weinstein once again in 2017, offering him $20,000 a month to help run interference for him and stop the multiple allegations of rape and assault from becoming public knowledge. That deal never actually ended up happening – but guess where Benza was working at the time?

It all goes back further still. Take another look at some of those covers of Talk.

Notice anything in particular?

All but one of the women on those covers would later go on to accuse Harvey Weinstein of some form of sexual misconduct (the exception being Nicole Kidman, who said she was only protected from Harvey’s advances because she was married to one of the few men more powerful in Hollywood than Weinstein at the time).

This particular tactic has eerie echoes of the one that American Media, Inc. employed when trying hush up the story of Karen McDougal’s affair with Donald Trump in 2016 – the incident that got Michael Cohen sent to prison and David Pecker and Dylan Howard cutting immunity deals with the FBI.

Rather than paying her off and then kicking her out into the cold, Pecker and co. did what Harvey Weinstein did: the exact opposite. They knew suspicions would be aroused if she was hidden away from sight after a huge pay-off, so they made a huge conspicuous deal out of welcoming her into the company family, using the corporate architecture of the AMI media empire to grant her a whole bunch of prominent, public-facing favours.

They put her on the cover of her magazines. They ran stories about her. They gave her a monthly column, which they effectively syndicated across multiple titles to give her some extra cash.

And where did Karen McDougal end up finding a writing gig?

Having a mini-multimedia empire like this affords an unscrupulous media mogul a million different ways to make his headaches disappear. So it’s no wonder that Harvey Weinstein was quite so keen to invest in Radar.

Nor is it any wonder why someone else would try to get himself in on the action when Radar‘s second funding round started…

In Part Two…

If you’ve read the National Enquirer story you’ll already know that Generoso Pope Junior didn’t just rely on money from a notorious gangster who wanted to keep stories about his poor professional conduct out of the press. He also took money from a second source. Arguably, an even darker one: the insanely corrupt Washington powerbroker, Roy Cohn.

Something similar is true of Maer Roshan too. In order to get Radar off the ground, he didn’t just rely on money from Weinstein. For its second round of funding, Maer would end up taking money from a man who was much more devious than Weinstein, and would die in abject disgrace just a few weeks after .

Not Roy Cohn.

The recently departed paedophile and child sex trafficker, Jeffrey Epstein…