Harvey Weinstein wasn’t the only suspect investor to stump up funds for Radar. Jeffrey Epstein whipped out his chequebook too. But what possible reason could a notoriously secretive billionaire with myriad ties to high society and a rumoured penchant for sex with young girls have for wanting to own a stake in a celebrity gossip magazine?

II/ A Social Animal

In January 1994, six months after having first met her, the famed Vegas illusionist David Copperfield whisked his supermodel girlfriend Claudia Schiffer away to a secluded spot in the Caribbean for a romantic getaway. His intention? To propose to her.

The location was idyllic. One of the few places left on earth where a world-famous entertainer could enjoy enough privacy to make his move on a world-famous supermodel. A hidden paradise, nestled deep in the heart of the Virgin Islands, a place so small and detached from the rest of civilisation that it’s only accessible by boat.

Paedophile Island.

That’s not its official name, of course. Officially, it’s called Little St James. Paedophile Island is just what locals on nearby islands took to calling it in honour of the guy who bought the whole place as his private residence a few years after Copperfield popped the question: Jeffrey Epstein.

It’s possible that the island is cursed, although we couldn’t tell you for sure. All we know is that Copperfield and Schiffer never married, separating after six years of engagement; Epstein – the island’s titular paedophile – died in disgrace in a Manhattan jail cell two weeks ago; and everyone who visited it between 1998 and 2019 – be they a politician, royalty, a society figure or celebrity – is about to get a knock on the door, as they’ve just become heavily implicated in a wide-ranging investigation into international child sex trafficking.

Paedophile Island plays an important part in this story. Not because of what went on there, necessarily. More because of what it symbolises. Paedophile Island was Jeffrey Epstein’s hideaway. His retreat. A place that was inaccessible to all but a few, especially invited insiders – bought as a way to keep his business secret.

Essentially, everything he’d hoped to find in Radar.

Nonce Upon A Time

There isn’t a huge amount to be learned from the very early stages of Jeffrey Epstein’s career – but to help give the most rounded picture of the dead perv that we can, we’ll quickly rattle through some of the major milestones.

1974: Initially, Jeffrey Epstein’s interest in children was put to good use: as a physics and maths teacher at the Dalton School, New York. There, Epstein’s passion for numbers impressed pupils so much that one of the parents soon got wind of his wizardry. He suggested that, with a brain like his, Epstein should be working in Wall Street – so put him in touch with a trader friend and recommended him for a job at the investment bank, Bear Sterns.

Epstein got the gig and switched teaching for trading.

1976: Starting on the bottom rung at Bear Sterns, Epstein worked as an assistant to the traders on the stock exchange floor – but not for long. He showed such aptitude for the work there that, within four years, he had been promoted right the way up the ranks from junior assistant to limited partner.

1981: This is where the Epstein timeline starts to get a little bit murky because, a year after becoming partner, Epstein was asked to leave Bear Sterns over an unspecified “policy violation”. Now that he’s dead, we’re entirely free to speculate as to what that violation might have been (financial mismanagement? An attempt at extortion? Some kind of sexual misconduct? Some combination of all three?). As far as the official line on it goes though, “policy violation” is all we’re getting. The incident is still shrouded in the utmost secrecy.

Epstein used this setback as an opportunity to strike out on his own, and started a couple of his own companies. The first of them was Intercontinental Assets Group: a kind of bespoke bounty-hunting operation for high-stakes financial crimes – a job which had him moving in the sorts of circles that gave his friends (and some federal investigators) pause whenever he would blithely claim that he was actually a secret intelligence asset to the CIA.

1988: A few years later he started another company, the one that has since garnered the most attention: J Epstein & Co – a wealth management service, exclusively for billionaires. Millionaires and multi-millionaires need not apply. Strictly high rollers only. If you weren’t hawking up an investment of $1bn or greater, then Epstein would politely turn you away.

That was the story at least, but it’s difficult to know exactly what went on with JE&Co because his list of ultra-wealthy billionaire clients has remained – even in death – extremely secretive. There are a couple of competing theories as to why that might be.

Some think the reason we know so little about it is because the company was basically a blackmail racket: a shakedown business in which Epstein would invite wealthy, well-connected investors to debauched sex parties at his properties, trick them into sleeping with minors, then procure big-ticket investments from them in exchange for his silence.

Others think it might be because his business wasn’t anywhere near as fruitful as he claimed; that the billion-dollar entry fee was self-aggrandising bullshit and that Epstein really only had one client: Leslie Wexner (the billionaire best known for owning and operating lingerie brand Victoria’s Secret).

It’s not particularly important which of those – if either – is true.

What is important is that no-one actually knows for sure.

This sort of mystery is a common thread throughout Epstein’s pursuits. In both work and in play, Jeffrey Epstein has managed to maintain an incredible amount of privacy regarding his affairs. A lot of that has been done by relocating the bulk of his work (and a fair bit of his play) to offshore tax havens in the US Virgin Islands, where it is much harder for authorities to properly uncover it.

However, like many men of his ilk, Epstein had a fatal flaw. It would eventually cause his unravelling, and it was best diagnosed by a former friend of his. Donald Trump.

The Holy Grail

“No doubt about it – Jeffrey enjoys his social life” – Donald Trump

Thanks to the very lucrative business of managing Leslie Wexner’s billion-dollar finances, Jeffrey Epstein had come into quite a bit cash by the end of the 80s, so he began to expand his property portfolio.

In 1990, he made one rather significant purchase, picking up a $2.5m mansion in Palm Beach, Florida. This was the same mansion that would later be searched by Palm Beach police in 2005 when they came looking for evidence that Epstein had been sexually molesting underage girls there.

Back when he first bought it though, the major point of interest about 358 El Brillo Way was that it was a stone’s throw away from one of the area’s glitziest attractions: Mar-A-Lago.

Mar-A-Lago had been purchased by Donald Trump five years previously and he had turned it into a highly prestigious private club. Anyone who was anyone in Florida society was a member and it wasn’t long before Epstein was a regular there too.

He was there in 1992, dancing with Trump and a bevy of young NFL cheerleaders, when a camera crew came to film there for the NBC News show A Closer Look.

He was there the night that Trump hosted a small soirée of 28 women who’d been invited to take part in a private ‘calendar girl’ competition (the only other man in the room, in fact).

He was there in 1997, photographed smiling, Trump’s hand on his shoulder.

He was there in 1999, when former Mar-A-Lago towel girl Virginia Roberts Giuffre claims that – aged 15 – she was approached by Ghislaine Maxwell (Epstein’s alleged recruiter) who asked her if she’d be interested in giving Epstein a massage back at his place.

He was there in 2000, photographed again posing with Trump, with Melania and Ghislaine.

And he was there until at least 2002, when Trump gave him the now-infamously glowing testimonial:

“I’ve known Jeff for fifteen years. Terrific guy. He’s a lot of fun to be with. It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side. No doubt about it — Jeffrey enjoys his social life.”

Point is: he was there a lot.

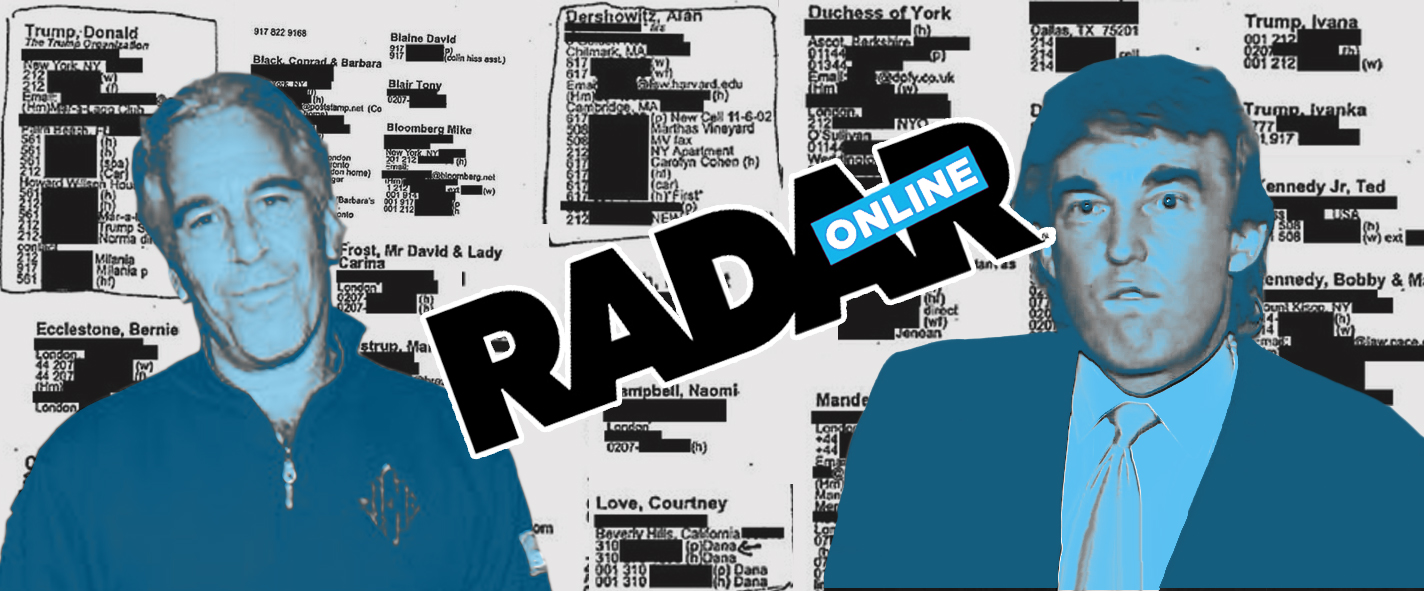

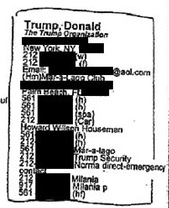

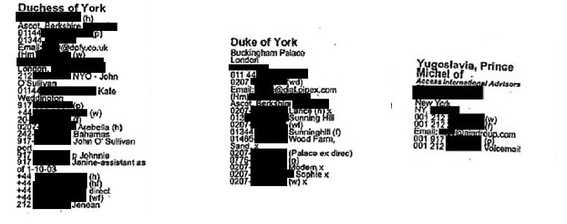

Epstein also held 14 different numbers for Trump in his little black book: the contacts book that earned the nickname among friends ‘The Holy Grail’.

Trump isn’t the only big name in Epstein’s contacts, of course. You can’t spend your time cutting between the social scenes of Florida and New York and not rack up a few big names in your phonebook.

And Epstein? He knew them all.

He knew royalty – like Prince Andrew, Sarah Ferguson, Prince Michael of Yugoslavia…

…politicians like Tony Blair, John Kerry, Mike Bloomberg…

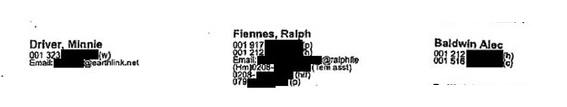

…actors like Minnie Driver, Ralph Fiennes, Alec Baldwin…

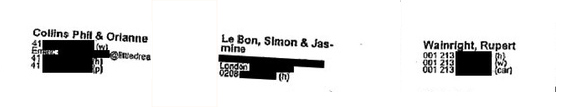

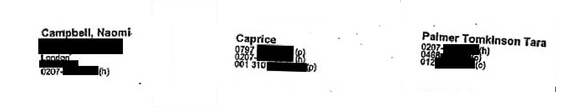

….musicians like Phil Collins, Simon Le Bon, Rupert Wainwright… …supermodels and society girls like Naomi Campbell, Caprice, Tara-Palmer Tomkinson…

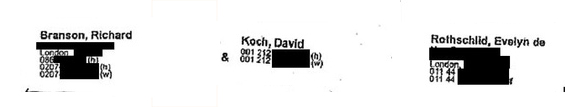

…supermodels and society girls like Naomi Campbell, Caprice, Tara-Palmer Tomkinson… …businessmen like Richard Branson, David Koch, Evelyn de Rothschild…

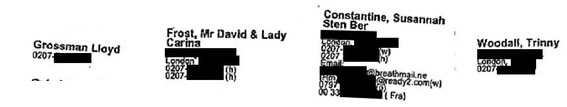

…businessmen like Richard Branson, David Koch, Evelyn de Rothschild… …television presenters like Lloyd Grossman, David Frost, Trinny and Susannah…

…television presenters like Lloyd Grossman, David Frost, Trinny and Susannah… …and, of course, #MeToo casualties like Charlie Rose, Dustin Hoffman and Kevin Spacey.

…and, of course, #MeToo casualties like Charlie Rose, Dustin Hoffman and Kevin Spacey. (He also had Toby Young listed in there, but we can’t hold that against him. Even dead disgraced paedophiles occasionally brush up against the wrong sort of people.)

(He also had Toby Young listed in there, but we can’t hold that against him. Even dead disgraced paedophiles occasionally brush up against the wrong sort of people.)

Unlike his buddy Trump though, Epstein wasn’t trying to cultivate any sort of public profile for himself with all this schmoozing. There were no cameos in Home Alone 2 for him. No Pizza Hut adverts. No appearances on Howard Stern. Instead, Epstein appeared content to court his famous friends mostly in private. Inviting them for dinner at his Manhattan mansion. Taking them for flights aboard his private jet. Hosting them on Paeodphile Island.

The trouble is, if privacy truly is what you want, you could hardly pick two worse places to spend your time than Manhattan and Palm Beach.

Because – thanks in no small part to American Media, Inc. – they’re absolutely crawling with reporters.

Neighbourhood Watch

If you’re familiar with our earlier story of the National Enquirer, you’ll maybe remember that Florida was where the Enquirer‘s founder-editor Generoso Pope Jr ended up in the 1970s, after escaping a rather spicy Mafia situation in New York (one that ended with Pope’s security guard being found dead in the back of a distribution truck, stabbed in the chest, the knife pinning a note to his chest that read “DON’T FUCK WITH US”).

Specifically, he ended up in Lantana.

One of the side-effects of Pope relocating his business there was that he inadvertently created a bit of an industry boom in the wider Palm Beach area.

Scores of reporters had flocked to Florida in order to take a job on the newly-relocated Enquirer. The pay there was great. The resources, practically endless. The only problem with taking the gig was that, more likely than not, you would find yourself getting fired by the famously capricious editor within weeks. That was just the way Gene Pope worked.

The churn of staff at the Enquirer was so great that, before too long, the bars of Palm Beach were spilling over with writers who suddenly had very little to do with their day. Pope’s cast-offs alone could have filled a tabloid magazine a hundred times over – and that’s pretty much exactly what came to pass.

Sensing there was an opportunity there, competing media organisations started setting themselves up in the neighbouring areas to start sopping up this endless stream of sacked hacks.

And lo! The Tabloid Triangle was born.

New titles were created. Pre-existing titles relocated. Soon there wasn’t just the National Enquirer snooping around Palm Beach. There was the Examiner, the Globe, the Sun – as well as countless other freelancers, stringers and bureaus.

Things would ramp up a gear again when Epstein moved down too, as 1990 was the year that the freshly-formed company American Media, Inc. started making its first proper move into acquisition mode – buying up Rupert Murdoch’s Enquirer-esque title, Star, to add to its shiny new stable.

Now, in 2019, American Media, Inc. owns almost all of them.

Epstein was very lucky to have such a good friend in Trump, as AMI has always taken a kind view of The Donald (even before his pal David Pecker took charge of the company in 1999). Trump’s playboy antics – The affairs! The divorces! The sensation! – were catnip to the celebrity tabloids, and a very welcome diversion for Epstein. Of course the Palm Beach press wouldn’t care about stuffy old financier bachelors with grey hair and bad clothes.

Manhattan though? That’s another situation altogether.

The Spy Who Loathed Me

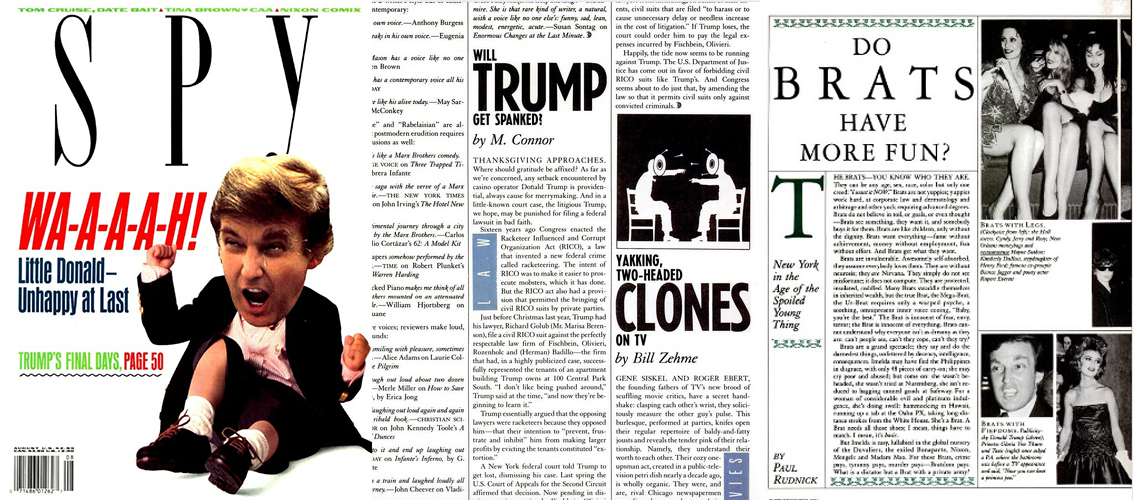

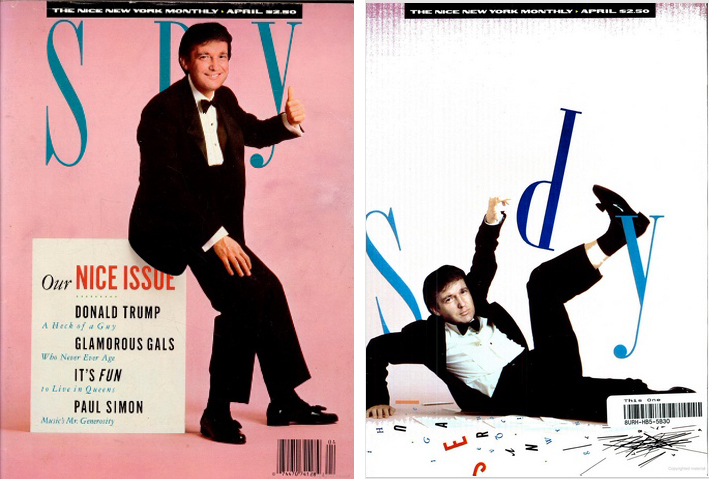

Over the years, you’ll have maybe heard Donald Trump described as being a “short-fingered vulgarian”. The phrase was first coined by Spy magazine, a hugely influential satirical monthly that covered New York society in the late 1980s and early 90s that made Trump (and his tiny hands) one of its primary targets.

Barely an issue went by without them trying to land a jab on him in one way or another.

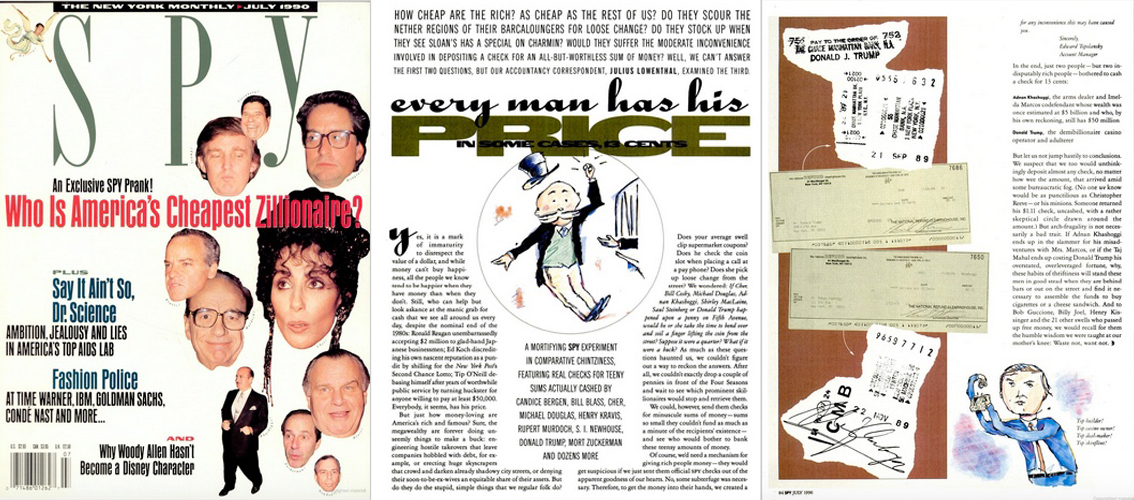

In one 1990 issue, Spy tried to find out who was New York’s cheapest zillionaire by sending some of Manhattan’s most well-heeled individuals a series of progressively piddling cheques to see who would keep going to the trouble of cashing them.

Trump was one of the contest’s winners, going so far as to cash a 13¢ cheque that Spy had issued to him through a fictional company. (He came joint first place: sharing the honour with the Saudi arms dealer, Adnan Khashoggi, who – by complete coincidence – had once hired the services of Jeffrey Epstein’s bounty-hunting company to chase down some other missing money for him.)

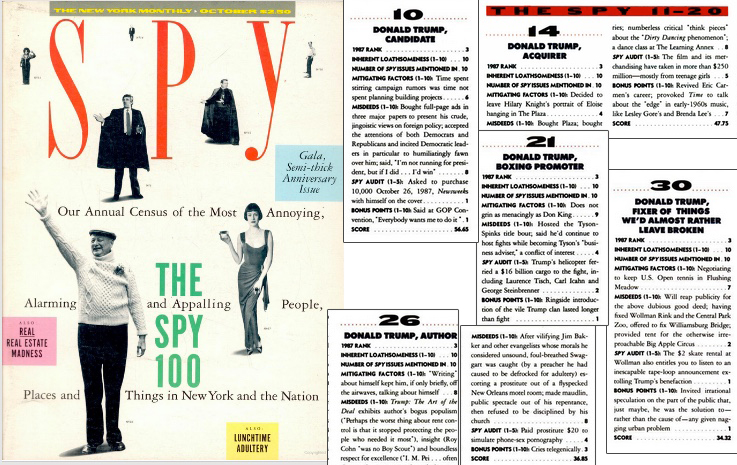

Trump would also regularly appear in the Spy 100 – a feature they described as their “annual census of the 100 most annoying, alarming and appalling people, places and things”. In 1988 Donald Trump had the unique distinction of being the only individual to appear on the list five separate times.

And all in the Top 30.

Their one attempt to be nice to Trump didn’t last much further than the front cover…

Spy got under Trump’s skin like nothing else. Never one to let go of a grudge, Trump continued to make a point of sending press clippings to the editors – long after they had sold the magazine and moved on to other titles. He annotated each of them in gold Sharpie, circling his fingers in the pictures and writing words to the effect of “SEE! PERFECTLY NORMAL HANDS!”

None of what Spy did to Trump was particularly hard-hitting journalism, but then the editors of Spy never once pretended that it was. Their main objective – arguably their only objective – was simply to flick the ear of the rich and famous. Be a pebble in their shoe. A wasp at their picnic. A magazine that existed to do little else but annoy the wealthy and powerful, by keeping a smart, scathing record of their conduct.

And if that mission statement sounds familiar, it’s because Spy was everything that Radar would seek to emulate (/imitate) 15 years later.

Had a mysterious Wall Street figure been taking people like Kevin Spacey, Bill Clinton and Prince Andrew on trips around the world aboard his private plane (one that was nicknamed the ‘Lolita Express’) when Spy was around, then it would have been exactly the sort of story to make its pages.

This is exactly what Epstein was doing around 2002-2003, which is the same point in time that Radar was being created (and not long before Epstein announced he was pledging $25m in funding, to buy up a controlling stake in the venture when the opportunity arose after Weinstein pulled out).

But the founding editors of Spy – Kurt Andersen and Graydon Carter – did more than simply set the stage for Radar. Both of them would each do one particular thing that would come to have a very significant effect on the way things turned out.

Kurt Andersen would take on the job of Editor-In-Chief at New York Magazine, where he would take a chance on hiring a brilliant new protege as his deputy editor: the man who would go on to found Radar, Maer Roshan.

We’ll expand more fully on New York Magazine’s role in all of this in Part Three. To finish Part Two though, we need to focus on what Graydon Carter did.

Carter left Spy to take on a big new job too: taking over from Tina Brown as Editor-In-Chief of Vanity Fair, the iconic high-society magazine.

Under Carter’s tenure, Vanity Fair would run the first major profile of Jeffrey Epstein. The 2003 article – entitled The Talented Mr Epstein – has undergone some renewed scrutiny in the years since Epstein’s arrest and re-arrest. A lot of it prompted by the journalist who wrote it.

In her research for the piece, Vicky Ward says she spoke to a mother and two daughters who described Epstein’s attempts to seduce them. She says she included their testimony in the original draft she filed, but their accounts never made it to print.

Ward has claimed, on multiple occasions now, that Graydon Carter personally intervened in the editing of that profile to remove the first-hand accounts of the women, telling her it because Jeffrey was “sensitive about the young women.”. Moreover, Ward says that Carter’s decision to do so only came after Epstein had showed up in person at the Vanity Fair offices looking to speak to the editor.

Carter, for what it’s worth, denies this characterisation of events, saying that Ward’s reporting wasn’t quite as tight as it needed it to be and that, besides, he can’t really recall the details.

The truth of the matter is actually of little consequence to us. The significant thing is that Epstein knew Vanity Fair was sniffing around him. He also knew that New York Magazine was trying to scoop Vanity Fair too (New York was the one that got that embarrassing quote from Trump, which came out in 2002).

Epstein wasn’t stupid. He could see his connections to the rich and famous were starting to make him a person of interest. He could hear the sort of whispers that were circulating around the newsrooms of New York. He knew the types of questions that reporters would ask, and the sort of angle they would take.

So his hand was effectively forced. If he wanted to have any hopes of protecting his reputation, like Harvey Weinstein before him, he would have take proactive measures.

He would have to get involved in the magazine business himself.

Luckily for him, an opportunity was making itself available. A plucky young magazine called Radar – thought to be the cultural successor to Spy, from Kurt Andersen’s old deputy – was in desperate need of some finance.

Could Jeffrey Epstein really afford to miss the opportunity to help out?

In Part Three…

It’s possible, in the way we’ve told this story, that we’ve given you the impression that Radar was the first publication that Harvey Weinstein and Jeffrey Epstein decided they wanted to fund. But that’s not quite true.

In fact, shortly before they turned their attentions to Radar, the pair of them had attempted to buy an entirely different magazine altogether.

Not as separate investors. Together.

Weinstein and Epstein were part of a rag-tag bunch of billionaires, millionaires and media insiders – a syndicate of sorts – known in the industry as The Coalition. All of whom wanted to buy New York Magazine.

Who was in The Coalition, and why does it matter?

We’ll explain…