Whispers are circulating about all sorts of celebrities and politicians and their various indiscretions at the minute, but how can you make sense of the reporting around these hushed up stories? Injunctions can force the hands of editors – but only so far. Here are the clues to look out for.

In-Jokes And Injunctions

First, a disclaimer.

By its very nature, this article is going to skirt the very edges of injunction law but what is contained below is published for NO OTHER REASON than to educate you on quirks of injunction law and the reporting surrounding them.

We are publishing this article to point out the many and varied ways in which journalists will attempt to drop clues about legally-binding injunctions. Our intent is to highlight the absurdity of our creaking injunction laws in a globally-connected digital age. It is not – we repeat, NOT – an invitation to start guessing on social media as to who may or may not currently have an active injunction in the UK.

If you want to do that (and we sincerely recommend that you don’t) you are entirely on your own. It is a gargantuan headache to deal with lawyers in this sort of case, and if you don’t think they have search columns and Google alerts set for their clients’ names and their designated injunction initials, then you gravely underestimate the modern lawyer.

We can’t say this strongly enough: publicly speculating about court-issued injunctions is a dreadful idea.

If you solemnly agree not to engage in any such activity, please read on.

If you don’t, you should know that there are much easier and cheaper ways to be sent to prison.

pb x

Last month, news of a brand new celebrity injunction hit the front pages: PJS v News Group Newspapers.

News Group Newspapers you may know as the publisher of the Sun and the Sun On Sunday. PJS is… well, we can’t tell you. That’s the point of the injunction. All we are able to tell you is what has already been made publicly available in the court ruling.

PJS is “a well known person who seeks to prevent a Sunday newspaper from publishing an account of his extramarital sexual activities”. He is “in the entertainment business” and married to YMA, who is “a well known individual in the same business”. The story involves “a three-way sexual encounter” outside of that marriage. They also “have young children”.

That’s about as much as we’re legally allowed to tell you which, admittedly, isn’t a huge amount.

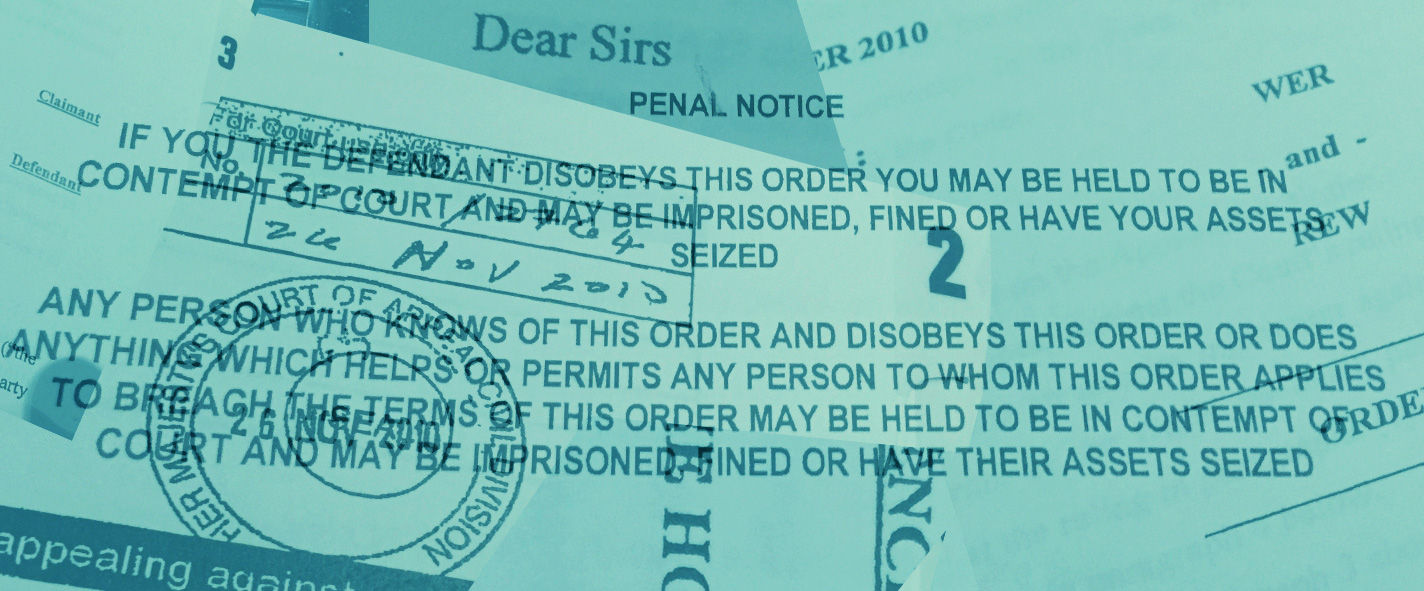

Journalists the length and breadth of Fleet Street are desperate to tell you more (especially now that the full story has broken in other countries) but, obviously, they can’t come right out and say who it is. Breaking an injunction puts you in contempt of court, which means that you are liable to be sent to prison – and journalists these days prefer to reserve prison for bigger ticket crimes, like phone-hacking or breaching the Data Protection Act.

Still, despite the legal pressure, sometimes they just can’t help themselves. The journalist’s urge to break a story is too strong, even when the law strictly forbids them from doing it. So what they do instead is try to find a way to hint at it, perfectly legally.

Small clues, almost imperceptible if you don’t know what you’re looking for, start to pepper their stories.

In-jokes, made with a wink and a nudge for those in the know, are cracked in their columns for the benefit of their colleagues.

Tiny shreds of information are eked out for people with prior knowledge. Enough to eliminate a few options, not enough to explicitly identify anyone in particular.

The whole thing starts to resemble a cryptic crossword: almost impossible to decipher if you haven’t got any idea where to start. But with a bit of practice, and a few tips on where to get your first foothold, you too can start to make sense of it.

So here, with the cautious blessing of our lawyer, is our guide to cracking the code.

Muck-Raking

Muck-Raking

One critical aspect of the anonymised injunction is that it applies only to the story, and not to the individuals themselves.

What that means is that an injunction (super, or otherwise) is not a blanket ban from mentioning that celebrity in any context, just the very particular context stipulated in the court order.

So if a resourceful young hack can manage to dig up a bit of unrelated dirt elsewhere on the celebrity (or celebrities) in question, then there is nothing stopping them from reporting that instead.

What you might start to see then is a string of old stories suddenly being reported on as a matter of urgency. Stories that date back a decade or more being positioned as breaking news. Stories that would ordinarily be tucked away in the bowels of the paper starting to float closer and closer to the front page.

Some of the less scrupulous papers might even try to create a story themselves, interviewing certain people who may have an easy axe to grind (an ex-partner, say); someone who is prepared to spill some separate, but not-entirely-unrelated, beans.

(If you get really lucky, you might find someone so ridiculously vain that they will even offer up their own stories and interviews as a way to remain in the papers and the public for the ‘right’, brand-approved reasons.)

This is not just a petty revenge tactic though. Nor is it simply an attempt to skirt the edges of an injunction for sport. If you can get other papers and news outlets to pick up on these stories, you can begin to amass a little portfolio that will help demonstrate to any presiding judge exactly why the celebrity under injunction is newsworthy, and why there is legitimate public interest in publishing the story that the celebrity wants torpedoed.

So even if the story doesn’t get the right rumours started, it’s still a very handy bit of supplementary material.

Repeated Reference

Repeated Reference

Similarly, see if you can keep a mental tally of the number of times that certain celebrities get mentioned in other stories. Not only will you find that the suspects get specifically singled out as the notable attendees at any film launches, star-studded galas, or awards ceremonies that they may happen to go to in the immediate aftermath of their injunction application, you will also find their name cropping up in stories about anyone who has even the most tangential connection to them.

It doesn’t matter how tenuous; if there’s a chance to get the name in print, then it will happen.

So if anyone is cropping a conspicuous and inexplicable number of times, chances are there’s a very good reason for it.

Full Press Assault

Full Press Assault

Although injunctions are usually taken out against one publisher in particular, the injunction itself covers everyone. This is to prevent other newspapers or organisations from finding the story independently and publishing it themselves.

So while it is a good idea to keep a particularly close eye on the news group named in the injunction (and any sister titles/channels they may have), remember that the injunction holds across all press – and other publications may be keen to help out and drop clues too.

Nothing brings the brotherhood of journalism together quite like a celebrity injunction. Especially as a whodunnit story is likely to up your own page views off the back of one of your rivals’ legal bills.

A Shift In Focus

A strange quirk of tabloidese is the habit of describing celebrities by their achievements. Even though they are phrases that no ordinary person would ever consider saying out loud, journalists don’t think twice about referring to Carly Rae Jepsen as “the Call Me Maybe singer”, or Steven Spielberg as “the helmsman of over thirty blockbusters”.

Ostensibly this little technique is used so that the writer doesn’t have to constantly keep typing out the celebrity’s name (as well as helping to deliver as much factual information as possible using just a few words). However, it also provides the perfect smokescreen for a bit of sneaky injunction busting.

It’s all about the choice of focus.

There are words we expect to see used with certain individuals. Take Bill Clinton. Let’s say he had tried to take an injunction out against a British newspaper trying to cover up the Monica Lewinsky story (which, obviously, he didn’t). And let’s say that injunction was granted, making it illegal for any journalist to publish the story, or explicitly allude to it. How would one go about dropping a hint that Bill Clinton was trying to cover that story up?

One way would be to use this technique. Instead of referring to him by one of the commonly expected descriptors (“42nd President of the United States, Bill Clinton…” / “Commander In Chief, Bill Clinton…”/ “ex-Governor of Arkansas, Bill Clinton…”) a journalist might ignore his political achievements entirely and instead chose to focus on his saxophone playing.

It’s a perfectly legitimate and accurate thing to bring up, but a fairly unusual one – one that will almost certainly give a reader pause.

“Famed horn-blower, Bill Clinton…” maybe. Or “Sax-mad Bill Clinton”. Nothing that screams “MONICA LEWINSKY GAVE CLINTON A BLOWIE”, but enough to tip off those scouting for clues that they’re getting warmer.

Clearly that’s a hypothetical example, but this happens a lot more than you’d realise.

Let’s say an actor took out an injunction to prevent stories leaking about him visiting a prostitute on the sly. Let’s also say that this actor had appeared in an otherwise unremarkable production of the play ’Tis Pity She’s A Whore early in their career. There’s no good reason to mention that, but you can bet your bottom dollar that that’s what the sneakier journalists are going to lead with next time they discuss that actor in print.

(And if that actor had paid the prostitute to shove something up their arse, an even sneakier journalist might try to slip a phrase like “bet your bottom dollar” somewhere in the copy too.)

Mental Imagery

Earlier this month (following a more subtle tip-off in the Popbitch newsletter), byline.com published a long article about the Secretary for Culture, Media and Sport, John Whittingdale MP, and his involvement with a dominatrix.

While there is no talk of an injunction in this instance, what makes this story particularly interesting for our purposes is that it had allegedly been placed in front of a number of newspaper editors who – for whatever reason – declined from publishing it.

There are many possibilities here. Those who suspect that a cover-up is at play suggest that, because Whittingdale’s remit includes press oversight and regulation, editors are keen not to get on his bad side. Particularly as Whittingdale is strongly supportive of a free press.

Others think that because Whittingdale is close to finally dismantling the BBC, the anti-BBC papers don’t want to do anything that would force him to resign.

It could be less shadowy than that, of course. It could equally be that there is no proof that Whittingdale has actually procured the services of the dominatrix in question (sex workers have lives beyond their business, like anyone else; they could simply be friends).

It could also be because the press doesn’t feel that there is sufficient public interest in a story about a single man making use of a dominatrix’s services as such behaviour is consistent with the libertarian values he promotes as a politician.

Whatever the reason though, the fact remains that this story has been well-known in journalistic circles for months. How can we tell? Take a look at this article, written in the Guardian, weeks before the story broke.

Had you not known that John Whittingdale had been accused of consorting with a dominatrix, then the sadomasochistic symbolism might have passed you by completely – but surely it’s no accident that it’s there.

To the uninitiated reader, it might look like Preston is the one who has a repressed desire to be manacled and whipped. To those who knew the John Whittingdale rumours though it was all tremendously funny – and Preston looks incredibly prescient when the story properly starts to break.

The Finer Details

The Finer Details

The law, for better or worse, is extremely precise in its wording. Lawyers may spend hours and hours arguing the toss over various interpretations of those wordings in court, but the judgements and orders that the courts issue are written incredibly deliberately and specifically.

If a legal order (like an injunction) is ever left vague then it is often for a very particular purpose. It’s important to know this because journalists can often give clues – either intentionally or inadvertently – by skewing the subtle details in their reporting.

Very clear examples of this has happened with this current injunction: PJS v News Group Newspapers.

The Guardian first reported the existence of the injunction on Tuesday 22nd March. The article mentioned everything we mentioned above: that PJS is a well known person who has engaged in extramarital sexual activities; someone who is in the entertainment business and married to YMA (also a well known individual in the same business).

All except for one crucial detail. The Guardian referred to YMA as PJS’s wife. The original judgement was very careful not to use the word ‘wife’, and the Guardian have subsequently changed their copy.

Then on Thursday 24th March, PR Week published this, Don’t Believe Everything You Read – The Privacy Injunction Is Alive And Well. In it, a senior associate at Farrer and Co uses gendered nouns which don’t appear in the original court papers. Far be it from us to tell a lawyer how to do his job (a senior one, no less) but he should probably re-read the order. And then get on the phone to his editor.

International Interests

International Interests

This is the big one.

Our injunction laws have been the object of ridicule, scorn and frustration as far back as the Spycatcher case of the late 80s. An injunction taken out in a UK court only has power over UK publications. In fact, it’s not even that strong. It technically only has power over publications in England and Wales. Just because someone has gagged a story here doesn’t mean that every other country in the world has to abide by Her Majesty’s court ruling.

So if an American publication wants to run the story that a celebrity has taken out an injunction in the British courts to suppress, the American publication’s only concern is editorial – is the celebrity sufficiently famous enough to warrant the space in their magazine?

Here, in the UK, the concerns are slightly more hefty. Is this worth a lengthy, expensive court case? Are we willing to risk a potential custodial sentence for publishing this?

To give you an example that isn’t quite so time sensitive, there was an injunction taken out back in the glory days of 2011 (an injunction which, we should point out, is still entirely in force).

The story, as best we are allowed to report it, is that two co-stars of a TV show had an off-screen extramarital affair. The male actor’s wife found out about it and it caused merry hell on set. The male actor then used his star power to have his female co-star kicked off the show. To quote the court papers, “the appellant told them that he would prefer in an ideal world not to have to see her at all and that one or other should leave” (which is legal speak for “it’s her or me”).

Given that he was the show’s star, the whole thing was a fait accompli. She was promptly let go and the story hushed up. We are unable to interview the woman in question and ask her how she felt to be the one fired from her job because her lover chose to cheat on his wife. She is unable to talk about it – and even if she did, we’re strictly forbidden from reporting her words.

Except that, if you live abroad (in the female co-star’s home country, for example) you’ll have seen this full story printed with names and details and descriptions. Where it is perfectly legal to report it.

Here in England and Wales, because no-one has the money or inclination to have the injunction overturned, the actor is buying everyone’s silence. For shagging his co-star, having her sacked, and paying to make the story go away.

A Final Note

A Final Note

Listen, we weren’t joking about that disclaimer up top. As much as you might feel that the law is unjust, as much as you might feel that everyone knows and there is no harm in joining in the big fun guessing game that always does the rounds when stories like this break, none of it is any defence.

Take these lessons. Learn from them. Then never speak of them again.