While mob boss Frank Costello gave the National Enquirer a connection to the less-reputable elements of society, in order to become a truly powerful publication it would need someone to introduce the Enquirer to the established corridors of power. Someone with the ear of a senator, an attorney general, a president. Which is exactly what it had in the rather lumpy shape of Roy Cohn.

II/ Angels And UnAmerican Activity

Here’s a question. What do the following people have in common?

– The state prosecutor who secured the death penalty for two American citizens accused of Soviet espionage during the Cold War

– The attorney who served as Chief Counsel for Joseph McCarthy at the height of the McCarthy witch hunts

– The lawyer who represented Donald Trump in his infamous racial housing discrimination suit in the 70s, and

– The man who, alongside mob boss Frank Costello, helped to bankroll Generoso Pope Junior as he acquired the National Enquirer.

The answer?

They’re all the same person. The disgraced, disbarred and dead lawyer… Roy Cohn.

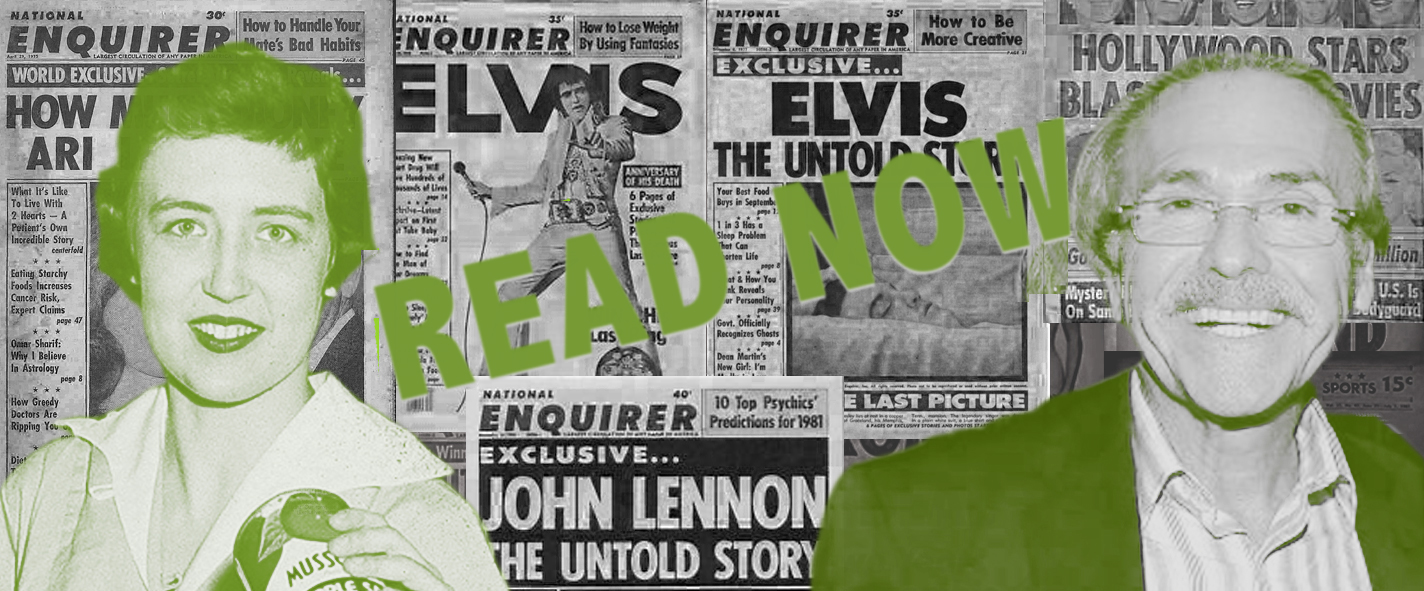

In the first part of this story, we looked at the National Enquirer’s first angel investor – Frank Costello – and how the combination of mafia money, mob mentality and one particularly threatening hit-job on a member of the Enquirer’s security staff inadvertently ignited a tabloid journalism boom in the early 1970s.

Something else very significant was happening around that same time though; a parallel story which involves the National Enquirer’s second angel investor, Roy Cohn. Combined, these two stories would go a long way to propel a critically derided gossip magazine into becoming an incredibly potent (and largely undetected) force in electing America’s stupidest president.

So before we push on, we ought to go back and trace this parallel story. Because mafia connections – helpful though they undoubtedly are – can only get you so far. Frank Costello might have had big-time operations in New York, Michigan, Illinois and Louisiana, but he didn’t command power on a truly national level.

In order for the National Enquirer to develop proper political clout across all fifty of the United States, Generoso Pope Jr would need the help of someone who moved in the world of politics.

And luckily for Gene Junior, he knew a guy.

About A Roy

About A Roy

Usually stories about Roy Cohn start with the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg – the famous espionage case that made Cohn’s name as a lawyer and brought him to national attention at the age of just 24.

Ours starts a touch earlier.

As a child, Roy Cohn attended the extremely prestigious Horace Mann School in the Bronx. A number of his classmates there would go on to take some pretty big jobs in the media. A kid called Si Newhouse would later become the chairman of Condé Nast, for example. Another, called Anthony Lewis, would go on to win two Pulitzer prizes. But it’s Roy Cohn’s carpool friend that we’re most interested in.

Every morning, Roy would take a chauffeur-driven limousine from the Upper East Side of Manhattan to Horace Mann alongside a friend of his who lived a few blocks over: Generoso Pope Junior, the boy who would become the de facto founder and creator of the National Enquirer.

The two boys enjoyed a special bond. As well as sharing their daily commute, Roy’s father would invite Gene Junior over to join the Cohn family for Friday night dinner each week. Gene’s father took a marked interest in Roy too, roping him in from a very young age to help out with some of his business deals.

At just 15 years old, Roy earned himself a $10,000 commission for helping Gene Senior negotiate a deal on the buyout of the radio station WHOM – money that Roy would then use to put himself through college.

But Roy wasn’t interested in a career in business like Gene Senior. Nor was he interested in one in the media like Gene Junior. Roy wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps instead. He wanted to get into law – and he didn’t waste any time in doing it either.

By the age of 20, Roy had already graduated from Columbia Law School – and he had to wait, just spinning his wheels, until his 21st birthday before he could be admitted to the bar.

He started work the very next day and within three years, he would be prosecuting something huge. A life and death case. One which would ultimately send two American citizens suspected of Soviet espionage to the electric chair.

The trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

Trial And Terror

Trial And Terror

Under normal circumstances, we probably could have breezed through this part – but, given that the topic of American citizens exchanging highly classified intelligence with Russian operatives is all the rage right now, it’s probably worth us taking a moment to talk in more detail about the Rosenbergs.

The case of the United States vs Rosenberg et al went to trial on March 6th 1951. In it, husband and wife team Julius and Ethel Rosenberg stood accused of attempting to transmit information about American military equipment and nuclear weapons (including documents from the top secret Manhattan Project) to the Soviet Union.

The Cold War was in its infancy at the time. Anti-communist sentiment was building up a decent head of steam in the States and the highly ambitious Roy Cohn – the 24 year old prosecuting prodigy for the state – was raring to go.

An absolutely ruthless operator, Cohn would take great pride in the fact that the Rosenbergs were given the death penalty, saying the punishment was handed down on his personal recommendation – with Cohn specifically angling to get Ethel the same punishment as her husband too, despite her much more limited involvement.

And it worked. Contentious though it was later considered, Ethel was sentenced to the chair. However, unlike her husband, the traditional three high-voltage shocks didn’t seem to stop her heart. There were still signs of life once the supposedly fatal procedure was over, so Ethel had to endure five full rounds of electrocution. Witnesses present claim to have seen smoke rise from her head. She died horribly and slowly.

The case made Roy Cohn’s name.

If any of this sounds vaguely familiar to you but you aren’t sure why, maybe you’ve seen Angels In America? For much like Frank Costello, Roy Cohn also made a couple of marks on the 20th Century culture too – most famously in Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer winning play.

In one scene, while on his deathbed, Roy Cohn is visited by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg who comes to break the news that he’s been disbarred. His years of unethical practice finally caught up with him, and he lived just long enough to experience that final humiliation.

The scene was famously portrayed by Al Pacino and Meryl Streep in the HBO adaptation.

How does the execution of the Rosenbergs relate to the National Enquirer? It doesn’t. Not directly, at least. But the timeline of the case is interesting.

The Rosenbergs were arrested in the summer of 1950. Their trial took place throughout March 1951 and they were executed by electric chair two years later in 1953.

It was during this same time that Generoso Pope Junior started talks to buy and take over the National Enquirer (or the New York Evening Enquirer, as it was then): a deal secured, in part, with money from Roy Cohn.

Now, Roy Cohn had always been a man of means (he rode a fucking limo to school, lest we forget) but this wasn’t pro bono work he was doing. He didn’t execute spies out of the goodness of his heart. This was his job. This is what he was paid to do. And he was not paid badly for it. It’s therefore not really much of a stretch to say that a significant chunk of the money that kept the National Enquirer afloat in its early days came directly from Cohn’s fees for prosecuting Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

And if it seems like we’re raising the issue to make some grand moral point here – we aren’t. Money is money, after all. Very little of it is clean (and Frank Costello’s contributions to the fledgling concern were decidedly dirtier).

The reason we raise it is because of the peculiar irony involved – as, before too long, someone else will unwisely (potentially illegally) trade some very sensitive political information with the Russians. Yet, far from being killed for it, they will be promoted to the highest office in the land.

And that is going to be – in part, at least – Roy Cohn’s fault.

Hearing Difficulties

Hearing Difficulties

It was during the Rosenberg trial that Cohn caught the eye of Joseph McCarthy: the senator from Wisconsin with a career-defining fear of communism.

Having seen Cohn successfully claim two commie scalps in court, McCarthy immediately snapped him up as Chief Counsel for the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations – the body that McCarthy used to investigate his suspicion that hundreds of stinkin’ pinkos were running amok in the US State Department.

The hearings, as you’re probably aware, became a national scandal.

McCarthy’s creeping paranoia is now the stuff of legend. So much so that his name has since become synonymous with the practice of levelling unsubstantiated, sensationalist attacks on people, accusing them of all manner of unsavoury behaviours on practically no evidence whatsoever (…sound familiar?)

He saw Reds everywhere. In government. In Hollywood. Under kids’ beds. To his mind, there was no part of American life that was free from Soviet influence. In that regard, McCarthy was very much the Louise Mensch of his day – except for the fact that he was (for a short while, at least) highly respected.

18 months of his aggressive and unhinged investigations would soon put paid to that – but Roy Cohn was every bit as responsible for the hearings jumping off the rails as McCarthy. He just wasn’t quite so public facing.

The two of them worked hand-in-hand: McCarthy, the nominal ‘brains’ of the operation; Cohn, the (occasionally literal) muscle. The pair routinely overstepped their brief, insulting, demeaning and castigating their witness.

Cohn was responsible for an impressive amount of the collateral damage too. He attempted at one point to throw a punch at his own co-counsel, Bobby Kennedy; he forged McCarthy’s signature on at least one document; and threatened, in all seriousness, to “wreck the Army” if the Army didn’t give a friend of his special treatment.

Yet McCarthy is the one who ultimately suffered for it. Censured by the Senate, shunned by his fellow Republicans, his reputation in tatters, McCarthy never managed to outrun the personal and professional damage inflicted on him by the hearings. He died four years later – at the age of 48 – of hepatitis, largely believed to be the result of alcoholism.

Roy Cohn, as more of a backroom bully, got luckier and managed to escape with the skin on his behind. He was still a young man. He still had a functioning liver. And now he had a prestigious CV and a little black book filled with some of the country’s most powerful contacts. So he took the collapse of the hearings as his cue to resign, and make the side-step into private practice.

And that’s where he really started to come into his own.

Private Malpractice

Private Malpractice

Armed with a contact book filled with the details of the great and the good, Roy Cohn promptly put it aside to begin representing some of the sketchiest shitbags going.

Among his clients were multiple bosses of the Mafia’s Five Families, including Carlo Gambino, Paul Castellano and John Gotti of the Gambino family; and Fat Tony Salerno, who served as consigliere, underboss and acting boss of the Genovese family (positions which were all previously held by Frank Costello, before he got shot in the head and incoming boss Vito Genovese changed the Luciano family name).

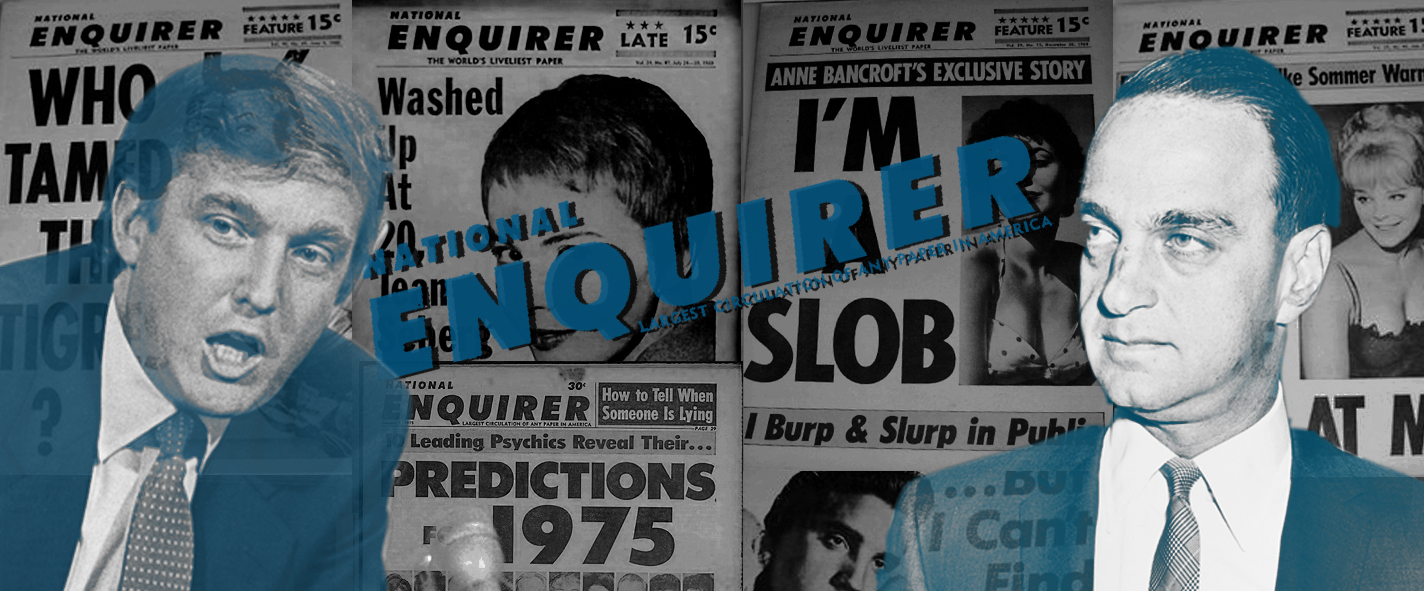

As well as his Mafia work, Cohn also represented a number of other well-known New York society luminaries, such as Andy Warhol, Yankees owner George Steinbrenner and – most relevant to our situation here – a Queens-born real estate developer and casino operator who habitually seemed to find himself in engaged in some legal scuffle or other, Donald J Trump.

Cohn and Trump met in 1973, under rather inauspicious circumstances.

Actually, the meeting itself wasn’t so bad. It took place in one of New York’s hottest nightspots (Le Club) and it clearly delighted Trump enough for him to single out the meeting for a mention in The Art Of The Deal. The inauspicious bit was the situation that Trump had found himself in.

’73 was not a banner year for the Trump brand. Young Donald was in the market for some legal representation because the US Department of Justice had just handed down a federal lawsuit, suing Trump and his father for racial discrimination. They claimed he had been deliberately thwarting potential black tenants from signing rental agreements by marking their applications with a “C” for “coloured”.

True to form, Trump refused to concede any fault whatsoever and, instead, began lashing out at the unfair discrimination that he was facing. This was exactly what Roy Cohn liked to see in a client.

The two subscribed to the same philosophy. Namely: never apologise, never settle and just keep fighting – no matter how pigheaded – until you get your way. So they filed a countersuit against the US government for “defamation” and “falsely accusing [them] of discrimination”.

Cohn and Trump obviously found a lot to bond over as they prepared the details of a $100m suit as they soon became firm friends. The 27 year old Trump, in particular, looked up to Cohn and treated him as a personal mentor. He had Cohn arrange the prenup that Ivana Trump signed. He had Cohn prepare the anti-trust suit he filed against the NFL when he tried to start his own football league in the 1980s. He had Cohn take care of the necessary zoning variances for Trump Plaza’s construction.

Curiously, Cohn never billed Trump for his time, claiming that he could never charge a friend (which is lucky, because Trump would never offer to pay either). Instead, in a similar sort of arrangement to the one he had with Gene Pope, Cohn kept Trump on hand in case he ever needed to call in a favour.

He was not shy about sharing his contacts with Trump either.

For example, it was Roy Cohn who introduced Trump and Andy Warhol. (Warhol was once a judge for a cheerleading competition that Trump had organised, but the pair fell out after Trump refused to buy a series of paintings Warhol did for him to hang in the lobby of Trump Tower.)

Roy Cohn was also the link between Trump and George Steinbrenner – the Yankees owner who Trump would later call his best friend, and who also made $100,000 in illegal contributions to Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign, then coerced his employees to lie to a grand jury about it. (He eventually received a Presidential pardon from Ronald Reagan, who Cohn aided.)

Trump didn’t just benefit from schmoozing with Cohn’s celebrity clients either. They were also good for business.

One of his Mafia clients, Fat Tony Salerno (who got his start running numbers under Frank Costello), just so happened to have a concrete pouring business – S&A. Guess who poured the concrete for Donald Trump’s first construction project in Manhattan?

Another of Cohn’s clients was Australian media mogul (and eventual Fox News founder) Rupert Murdoch. Guess who introduced him to Trump?

To top it all off, Cohn was the one responsible for introducing him to the media strategist, political consultant and self-described “dirty trickster” Roger Stone – the man who ultimately convinced Trump to run for office (put a pin in that name for the moment; we’ll revisit Roger Stone in Part Four).

Not for nothing did Roy Cohn boast that he “made Trump” – and if there’s anyone who Trump could be cajoled into conceding had “made” him, it would likely be Roy Cohn. He was the one who taught him to lean in to his infamy. The one who taught him to fight back, no matter the moral consequence. And the one who taught him that, so long as you’re drawing breath, there’s nothing a good lawyer can’t get you out of.

Roy Cohn was a prime example of it.

The Cohn Legacy

The Cohn Legacy

Cohn’s career in private practice was what one might charitably describe as being “chequered”.

Or, if you want the official verdict handed down by the Appellate Division of the state Supreme Court in Manhattan: “unethical”, “unprofessional”, “particularly reprehensible”, with his own testimony being ”untruthful, misleading and [showing] evidence of highly unprofessional conduct.”

His rap sheet was about as long as they come. He spent most of his career after he left McCarthy under some sort of indictment or other; accusations which he always managed to shake off.

He was under IRS audit for 19 years on the trot. He was hauled up on violating Illinois banking laws. He drew accusations of perjury. He was suspected of witness tampering. Misappropriating clients’ funds. Falsifying information on official documents. Breaking into the hospital room of a dying, senile millionaire and taking their drugged and semi-conscious hand to trace their signature, so that he could make himself a co-executor to their will.

Conspiracy, bribery, fraud. If you can name an unethical, immoral or otherwise unpleasant practice – the chances are that Roy Cohn has been accused of it. The chances are he engaged in it too. He just managed to dodge copping to most of it.

Until the very end, at least.

Six weeks before he died, Roy Cohn was disbarred. He had been charged with multiple counts of serious malpractice and, despite the glittering array of acquaintances prepared to testify as a character witness for him (among them, one Donald J Trump), it was no use. He had made too many enemies. Weak, sick and dying, he now suffered the greatest indignity of all. He was stripped of his license – and it crushed him.

But while the bullishness and the brutishness of Roy Cohn is important to understand, it’s not what makes him an important player in this story. It was his conniving side. His sneaky, secretive, gossiping side.

Part of the reason Cohn was able to manage his career so successfully, despite the constant threat of indictment and disbarment, was that he was connected. Not in the way that Frank Costello was connected, perhaps, but not exactly dissimilar either.

The law stuff was really just a way in for Cohn; it was secondary to the power-broking. You could see it in his choice of clients. He didn’t take on Mafia dons out of devotion to the law. He didn’t represent the Trump Organisation because he was motivated by the pursuit of justice. His only pursuit was the pursuit of power.

Deep down, Roy Cohn was a gossip. Dishing dirt was at the very heart of his business. Not only was he friends with all of the major gossip columnists and society reporters, he actively used their papers and magazines to leak stories, to spread rumours, to gather leverage. He involved himself in everybody’s business, whenever he could. He had his assistant record all of his phonecalls. He would lie to reporters about having signed clients, promise to provide proof of it, then fail to follow through on it once he’d got his headlines (…sound familiar?)

Far from this bringing disgrace upon his name for the forty years that he was in practice, it was one of his major selling points – both as a lawyer and an ‘informal advisor’.

So it made perfect sense that he would be so invested in the National Enquirer. Emotionally, because it was the baby of his childhood friend Gene Pope; professionally, because it was a useful way for him to spread muck on his opponents; financially, because he had thrown tens of thousands – if not hundreds of thousands – of dollars to keep it afloat in its infancy.

It was the perfect tool for him.

And it would be the perfect tool for the protégé he had formed in his own image, too: Donald J Trump

In Part Three…

In Part Three…

So here we have the National Enquirer: funded and flanked on one side by the Mafia, funded and flanked on the other by America’s best connected lawyer.

The tabloid is one degree of separation from anyone you could care to mention, from high brow to low – from the White House to the Big House; the US Senate to Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

However, don’t think that any of this means Gene Pope wasn’t responsible for making the Enquirer everything that it managed to become, because he very much did.

No-one was buying this tabloid magazine because Frank Costello was an early investor in it. The number of people who picked up the Enquirer because its connection to Roy Cohn was one – Roy Cohn. These people aren’t who made the Enquirer a success. Gene Pope was.

His vision for the Enquirer was his and his alone, and anyone who worked for Gene Pope throughout his reign will tell you the same.

But it’s important to establish that all these various players had a stake in it too – because when Gene Pope finally hit upon his magazine’s masterstroke, he gave these same people a direct line into more than six million suburban homes across the length and breadth of America, and attracted the attention of many millions more.

And what’s so crazy about it is that Gene Pope’s masterstroke was so simple, so effective and so obvious it’s hard to believe that nobody really did it sooner.