The criminal underworld of New York, the closed corridors of Washington, the magazine industry of Florida. They’re all very interesting – no question about that – but these aren’t regular people we’ve been talking about here. For the National Enquirer to cut any sway with millions of average American Joes, things would have to change. They’d have to go corporate. Which is where American Media, Inc. comes into play.

III/ Suburban Decay

So far, our story has concerned itself specifically with the National Enquirer. In particular, the situations of its two shadowy investors: mob boss Frank Costello, in Part One; and political powerbroker Roy Cohn, in Part Two.

So far, our story has concerned itself specifically with the National Enquirer. In particular, the situations of its two shadowy investors: mob boss Frank Costello, in Part One; and political powerbroker Roy Cohn, in Part Two.

In doing so, we have potentially underplayed the role that the magazine’s creator, Generoso Pope Junior, had in the whole affair. Not only in making the National Enquirer a massive success (which he unquestionably did) but in revolutionising the entire celebrity tabloid industry. For there was one decision in particular that Gene Pope took in the late 1960s that would affect an entire genre of magazines – and would do so so monumentally that the effects of it are still being felt, 50 years on.

We have also yet to touch on the larger corporate force at play here, that of American Media, Inc. (And although Gene Pope wasn’t the one who created AMI, there is no denying that it was built – pretty much exclusively – off the back of his hard work.)

So let’s leave the Mafia and the Washington elite behind for the moment. Instead, let’s take a journey into the deeply sexy world of magazine distribution networks to see exactly how the minor nuts and bolts of the publishing industry of mid-century America played a part in enabling the inexplicable election of Donald Trump in 2016.

It’s not spoiling anything to tell you that by the end of this chapter Costello, Cohn and Pope will all be dead. What will remain of them are the loose ends of the thing they started together. All of which will be picked up and continued by a man with a name that you have to promise not to laugh at.

A man called David J Pecker.

Market Forces

At some point in the mid-1960s, Generoso Pope Junior, creator and owner-editor of the National Enquirer, found that his sales were stagnating.

For fifteen years, the Enquirer’s trademark blend of gossip, gore and true-life stories had proved to be a huge hit. The ailing regional broadsheet that Gene Pope had bought up (which struggled to reach 20,000 readers on its best days) had been transformed into a national smash hit tabloid, selling upwards of a million copies each and every week.

That seemed to be its ceiling though. Gene Pope would laughingly suggest that this was because there are “only so many libertines and neurotics in the world”. Privately though, he was desperate to know why sales had tailed off. Around that same time Reader’s Digest was ordering print runs of 18 million, so it’s not as if magazine buyers were in short supply. So what was causing the plateau?

Pope soon discovered was that it wasn’t down to a lack of interest in the Enquirer. It was down to a lack of opportunity.

Earlier that decade, in 1962, New York had been hit by a newspaper strike. 17,000 employees from seven major newspapers had downed their tools and stood up to their bosses about their wages and work rules.

The strike ended up lasting almost four months and the results were devastating to the industry. Four of the seven striking papers didn’t survive it, and the ones that did discovered that their news-starved readers had been driven into the arms of other, less-fastidious sources. They had turned to TV, they had turned to magazines, they had turned to the National Enquirer – and when the strike was dissolved, they didn’t all turn back.

In the short term, this strike really helped the Enquirer as they continued to publish throughout. In doing so, they packed on a number of new readers.

Long term, however, it led to a rather unhelpful development.

The overwhelming majority of the its sales, week to week, were impulse purchases from newsstands; passers-by plucking it off a street-side vendor on their lunch hour, or on their way home. After the strike of ‘62 though, with fewer major newspapers still in circulation, these city newsstands began to close.

With no real subscription base in place to fall back on, these closures would severely hamper the Enquirer’s sales opportunities – but there was another problem too.

The Enquirer‘s readership had grown up. They’d settled down. They’d started families. They’d bought up the newly built houses out in the suburbs. They’d become – to be blunt – middle class arseholes.

Now, there’s nothing inherently incompatible about being a middle class arsehole and a National Enquirer reader, so it’s not as if any of these sales were lost for good. In fact, taken together, these two problems actually presented a single, complementary solution.

If Gene wanted to keep his sales up, all he had to do was pull his product from the sinking inner-city newsstands and start stocking them wherever all the middle class arseholes were.

And where, in 1960s America, was that?

Supermarkets.

It was the perfect plan. Not only would stocking the Enquirer in supermarkets put it back in front of the people who were most likely to buy it, it also opened up a whole new potential customer: the weekly suburban shopper.

(Supermarkets also had the added benefit of using an entirely different distribution network to the one that city newsstands used, which meant that Gene Pope would no longer have to deal with whichever gangsters had been hijacking his print runs, knifing up his security staff and pinning swearwords to their chests.)

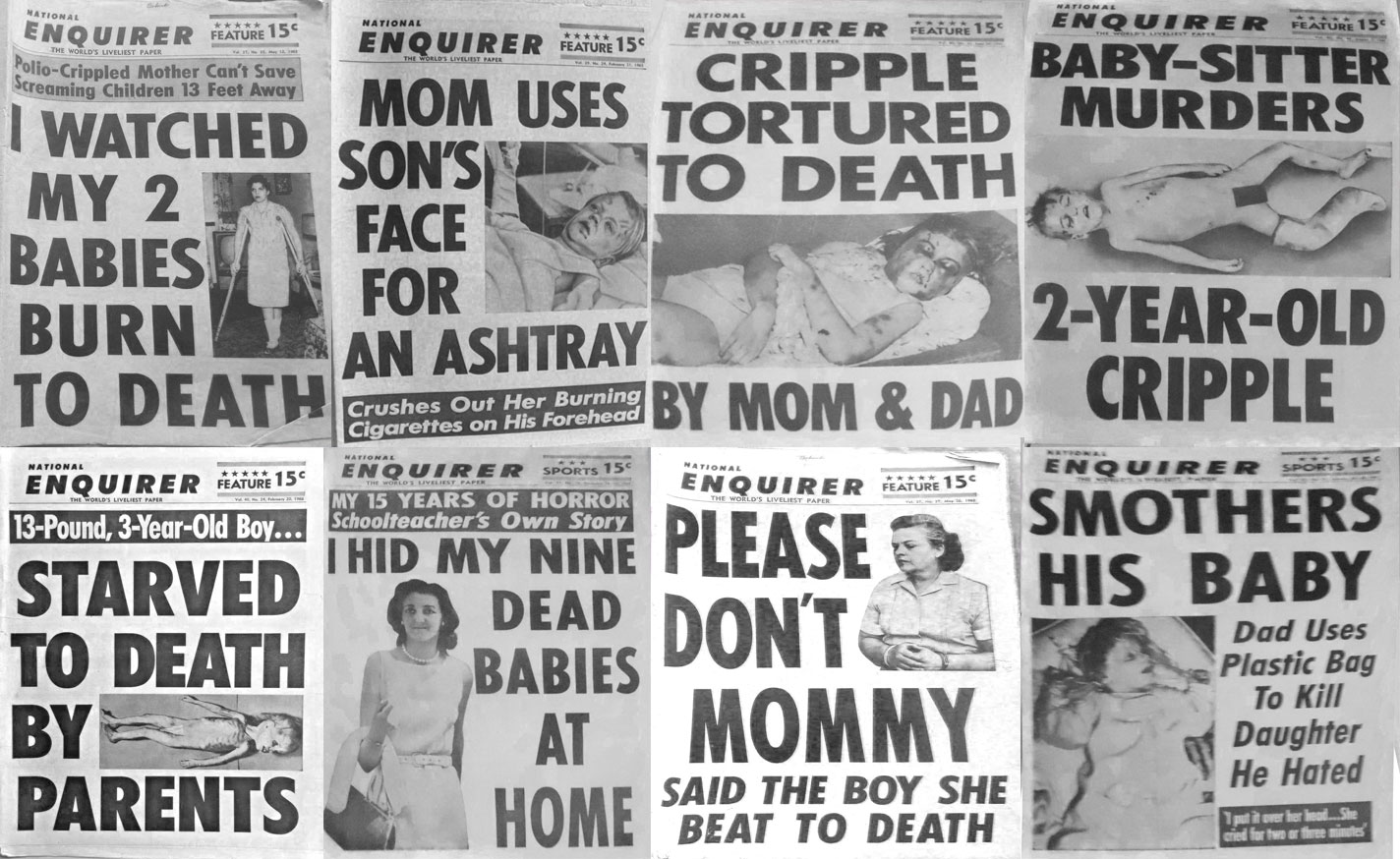

The only snag now was the Enquirer’s content. It wasn’t always the gaudy, sex-and-scandal sheet we know it as today. Back in the 1960s it was absolutely bleak as fuck, and really not suitable for people of a sensitive disposition (so get ready to scroll fast if that’s you).

Gene Pope had his work cut out here, as supermarkets were supposed to be family friendly places. No respectable supermarket owner in their right mind would want to stock a magazine which regularly ran front page splashes like this…

If the Enquirer was going to succeed in the supermarkets, changes would need to be made. In modern media speak, it would have to ‘pivot’.

So out came all the pictures of mutilations, decapitations and cigarette-burned children that had proved so popular on the mean streets of New York; and in came the sort of softer, lighter material that the casual supermarket customer was better disposed towards.

Medical breakthroughs. Miracle stories. Rags-to-riches tales. And the one thing that would later come to define the magazine completely: celebrity gossip. This pivot would prove to be a huge hit, quadrupling the Enquirer‘s sales over the subsequent decade up to four million copies per week.

But the real genius of Gene Pope’s plan was still to come.

Rack ‘Em Up

The National Enquirer had something of a bad reputation within civilised society. Sensationalist smut rags were not considered to be the sort of thing that should sully up a wholesome family supermarket, so Gene Pope really had to hustle to convince the owners of these stores to take a punt on him.

His plan was two-fold. On one side, he would drum up a bit of good PR and get it in the hands of some respectable types. Some honourable brand ambassadors.

To that end, he placed a couple of calls to a few well-placed individuals and, before too long, Gene Pope had a picture of Richard Nixon leafing through a copy of the National Enquirer (who just so happened to count among his campaign advisors, a certain Roy Cohn).

The pitch was simple: if it’s good enough for a Presidential candidate, it’s good enough for the shoppers of Poughkeepsie.

Good PR wouldn’t be enough on its own though. The store bosses of the Sixties were serious businessmen and they wanted to talk cold, hard numbers. So, to further sweeten the pot, Gene cut them a very special deal.

In return for displaying the Enquirer at their checkouts, not only would the supermarket get to keep a slice of the cover price for any copy sold, Gene Pope would also take care of manufacturing the magazine stands himself. The actual, physical racks that the National Enquirer would be displayed on in their store would be provided at no cost to them.

To the bosses, this was a no-brainer. They didn’t have to lay out a single penny. The area Gene Pope was interested in was a total dead space. And now that the Enquirer wasn’t going to be featuring brutalised babies on its front cover any more, there was really no good reason to say no.

So the deal was done. And while the shift into supermarkets was an exceedingly smart one, it was manufacturing those stands that would prove to be Gene Junior’s shrewdest move. Because it wasn’t too long before Rupert Murdoch, the New York Times and Time Inc would all attempt to launch their own weekly downmarket tabloids too – and they would all be after a slice of the same action.

Add those to the handful of other publications that had already been trying to ride on the Enquirer’s coattails from the start (magazines like the Globe, the National Examiner and Sun) and you have at least half a dozen major titles that were jockeying for readers’ attention.

In any other industry, having to share a supermarket shelf with your six primary competitors would be less than ideal – but it didn’t seem to bother Gene Pope. In fact, he welcomed it. Not because he thrived on the challenge particularly. Because he owned the shelves.

The deal he hammered out with the supermarkets meant that, in manufacturing and providing them, the magazine racks remained Gene Pope’s property. That being so, Gene Pope was the one who got to decide who and what got displayed at the checkout.

Naturally, he reserved the primo spots on the rack for the Enquirer. The rest were fair game for any other magazine that was prepared to rent them off him. And the more competition there was in the industry, the more valuable that rack space inevitably became.

Therein lay Gene Pope’s genius. For not only did these competing titles have to give away a portion of their cover price to the supermarkets, they were also having to pay their major competitor, Gene Pope and the National Enquirer, weekly rent in order to display their product next to his.

On his National Enquirer-branded racks.

Effectively, in creating these racks, Gene had started a profitable little sideline for himself in the real estate business. And in doing so, unwittingly, he had also sketched out the broad business model for the company that would emerge from his estate twenty years later: American Media, Inc.

A Phoenix From The Trash

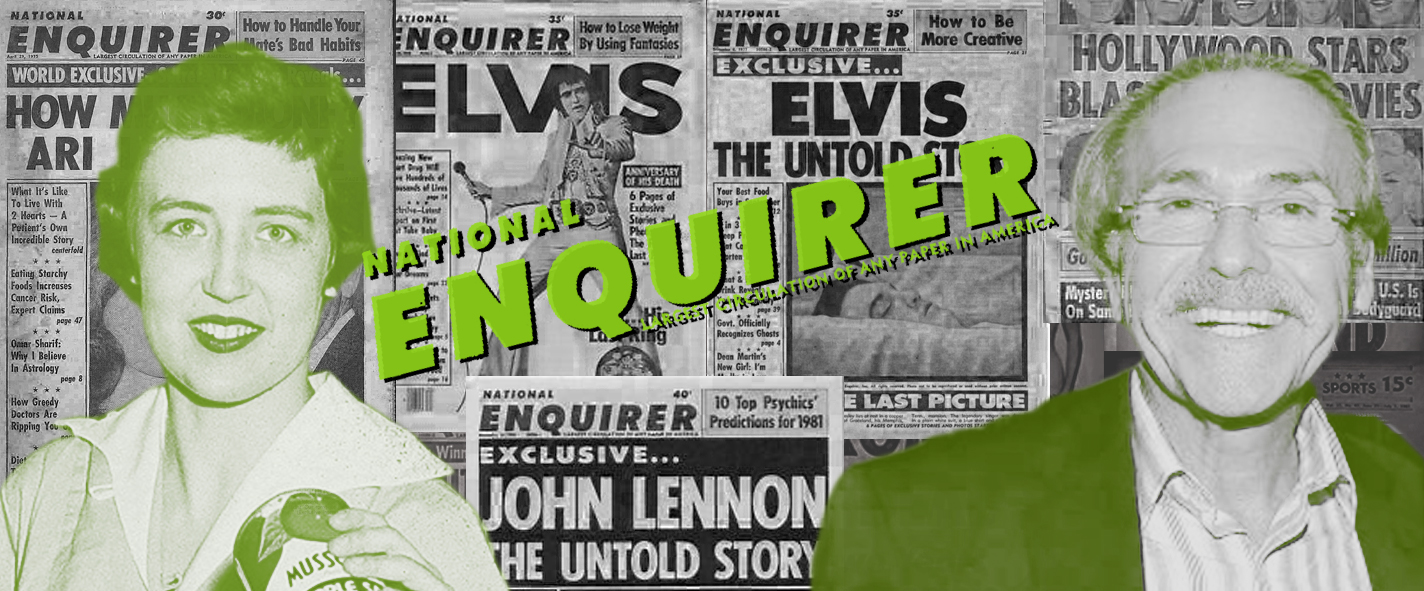

Generoso Pope Junior died in 1988, leaving behind a wife, Lois, and six children. As executors of his estate, they made the decision that the National Enquirer be sold. So it was.

Like almost every business transaction ever conducted, the details of it are extremely boring. The important topline, however, is that the Enquirer sold for $412 million and would become the founding asset in a new company: American Media, Inc.

The mission of American Media, Inc. was simple. To buy up as much of the American supermarket tabloid industry as it possibly could, bit by bit. In short: consolidate the Tabloid Triangle.

Establishing its offices right in the heart of that triangle (Boca Raton, Florida) AMI began the slow, steady process of scooping up the major supermarket tabloids under one big corporate umbrella.

Having started with the National Enquirer (and its erstwhile sister publication World Weekly News), the first competitor to be brought into the AMI fold was Rupert Murdoch’s Star in 1990. Murdoch hadn’t been enjoying the US tabloid game anywhere near as much as he thought he would, so sold up to focus on his other American ventures (the New York Post and, later, the founding of Fox News.)

In 1999, AMI expanded again to engulf all of the Globe titles, meaning that Globe magazine, the Sun and the National Examiner all became a part of AMI too.

In 2002, it broadened its scope and bought up Weider Publications: a stable of health and fitness magazines including Men’s Fitness, Muscle And Fitness, Flex and others.

In 2011, it finally managed to get its hands on Soap Opera Weekly and Soap Opera Digest (magazines which Rupert Murdoch had owned in the past, and which had passed from pillar to post for years and years).

And the buy-up still hasn’t stopped.

Earlier this year, in January 2017, there was a rumour going around that AMI was looking to buy up Time, Inc. (a merger that would have netted the company People magazine) but it never ended up happening. Instead, after a surprise about-turn in March, AMI made a $100m purchase of Us Weekly.

There are still rumours that AMI has Time, Inc in its sights – and more recently there is talk that AMI might try to buy Rolling Stone (which was put up for sale last month by the same publishers who previously held Us Weekly).

All in all, it makes for an impressive (if somewhat unprestigious) stable. Once they were all competitors, vying for space on Gene Pope’s racks. Now, thirty years on, they are all brothers and sisters. Siblings in the same, scandal-driven family.

But how, you may be asking, does any of that help? Scooping up a bunch of like-minded businesses might be good for your bottom line, but how does controlling Soap Opera Weekly, the National Examiner and Men’s Health help elect anyone to high office? Let alone someone as spectacularly batshit as Donald Trump?

The answer to that lies not with Gene Pope Junior, but with his father.

Empire Of The Son

In many ways, Generoso Pope Junior was every bit his father’s son. Ambitious, driven, successful, powerful. But there was one big difference – and it is here where we see it at its starkest.

Under Gene Junior, the National Enquirer soared. There’s no question about that. He took on a two-bit newspaper that was barely even used to line litter trays, and he transformed it into a magazine that sold six million copies on a good week. By every measure it was a massive success (certainly miles more successful than any of the publications that Gene Senior ever ran) but Gene Junior never really enjoyed the same sort of power that his father did.

That’s because, while Gene Junior knew how to build a magazine, Gene Senior knew how to build an empire.

If you were an Italian immigrant in New York or Philadelphia in the first half of the 20th century, the chances were that Gene Senior was in charge of almost all of the news you saw. He owned Il Progresso Italo-Americano and Il Bollettino della Sera. He owned Il Courier d’America and L’Opinione. No single publication of his was a huge smash hit. None of them sold multi-million copies – but that didn’t matter. He didn’t have to be the best in the business. Not when he was the business.

The breadth of Gene Senior’s reach was the key to his influence. No matter where people looked on the newsstands, Gene Senior was catching their eye. And if he wasn’t doing that, he had his radio station WHOM.

Gene Junior got close to doing the same thing, but not quite. In building those racks and charging his competitors to be displayed on them, he was making a decent chunk of money off the back of them – but he wasn’t capturing their audience. And that’s where the real power lies.

Generoso Pope Senior knew that. That’s why he could get candidates elected, both at home and abroad. That’s why Mafia bosses didn’t take advantage of him. That’s why presidents reached out to ask him favours, rather than the other way round. Gene Senior knew the power of an empire.

You know who else knew it too? David J Pecker.

Pecking Order

The ins and outs of David Pecker’s employment history before he joined American Media, Inc. are not wildly illuminating for our purposes – save for one small detail.

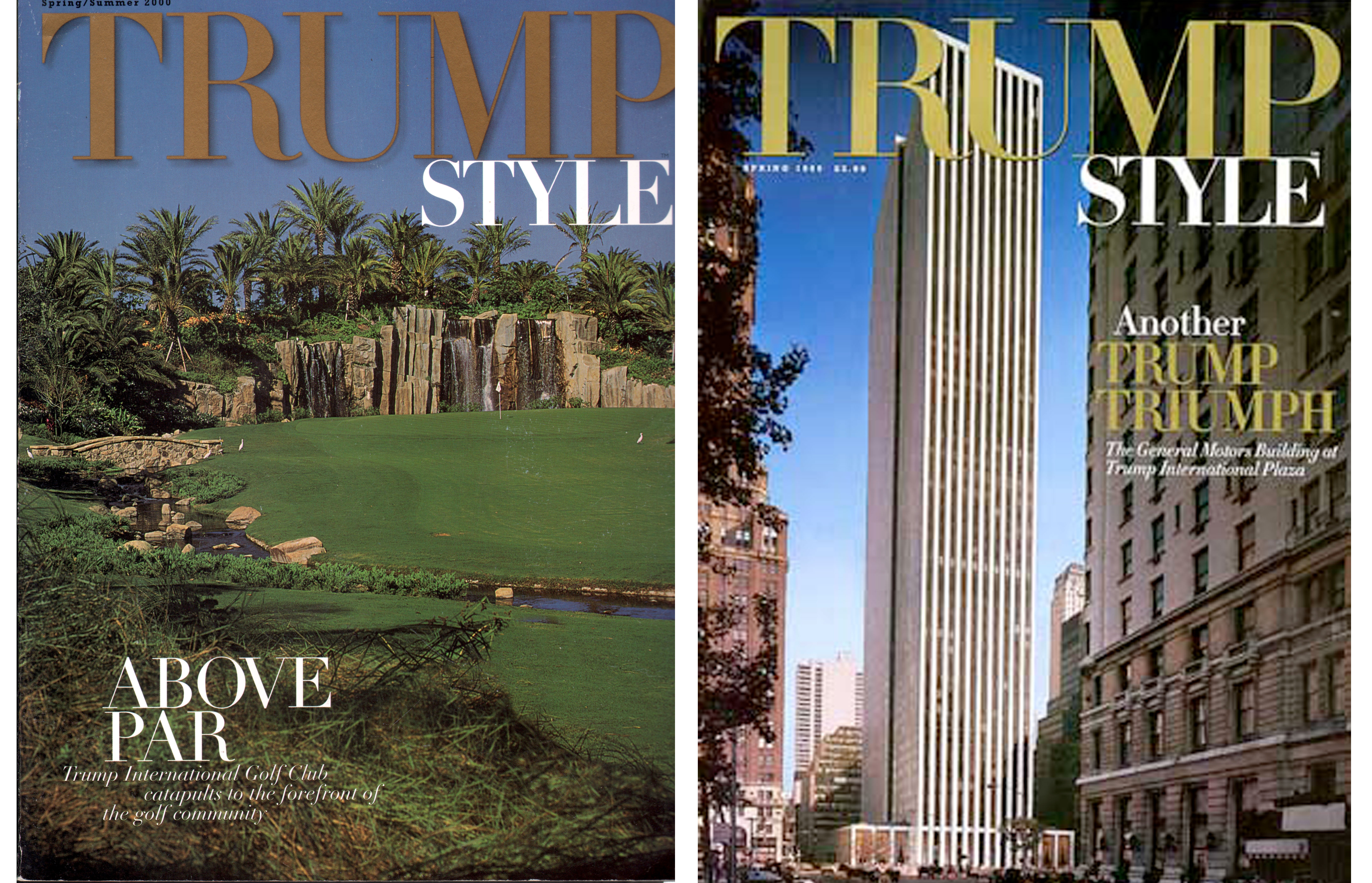

In 1997, while he was the CEO of esteemed publishing house Hachette Filipacchi, Pecker set up a ‘custom publishing’ operation. There, he oversaw the contract to produce one particular vanity project, a garish quarterly whose 130,000 captive readers were largely concentrated in Palm Beach, Florida.

A magazine called Trump Style.

Sadly, there is little that remains of Trump Style. Presumably few people expected the scowling grump on the contents page would go on to become the first world leader to announce a thermonuclear war on Twitter – so copies of it are pretty hard to come to by nowadays.

It’s not hugely important though, as the critical element here is that Donald J Trump and David J Pecker have enjoyed a professional, media-focused relationship for about twenty years now.

We’ll discuss in Part Four why that relationship was particularly helpful for Trump’s presidential ambitions (and was so even as early as 1999). For now though, let’s address a question that may have occurred to you a little further up-page. A question that helps to shine a light on the benefits of owning a wide-ranging media empire.

Specifically: how on earth does buying up a raft of health and fitness titles help to elect a president who exists solely on cheeseburgers and chocolate cake?

The key to that little mystery is Karen McDougal. And if you have to ask who Karen McDougal is, then David Pecker has done his job correctly.

The Disappearing Bunny

In November 2016, just days before the US election, a story broke in the Wall Street Journal alleging that a former Playboy playmate had sold a story to the National Enquirer; a story in which she claimed to have had a ten-month affair with Donald Trump in 2006-07, during his marriage to Melania.

This would have been an absolutely dynamite story had it got out (especially hot on the heels of the leaked “Grab ‘em by the pussy” tape) but, for some reason, the National Enquirer never ran it.

Moreover, it transpired that they had forked out a substantial $150,000 for it – and had been sitting on it for at least three months before the Wall Street Journal found out.

Now, it’s not uncommon for a publication to buy up the exclusive rights to a story and then sit on it. This is especially true when stories could potentially embarrass a personal friend of the proprietor (the proprietor in this case being David Pecker; the personal friend, Donald Trump).

As a single magazine, that $150,000 would be a sunk cost. You’ve bought the source’s silence (which, ultimately, is what you wanted) but that’s all you get.

When you have a media empire like AMI, however, you get a lot more for your money.

First: in owning most of the industry competition, you severely limit the number of publications a source can turn to to sell their story. This helps to stifle any sort of crazy bidding war; therefore you get your stories much cheaper than you would as an independent title.

Second: you can be a little more creative in your demands. A $150,000 payment to strike an exclusive deal with a random former Playboy playmate for a story they can’t print is a lot of cash. It also looks a little bit suspicious – like you might deliberately trying to be spiking stories that could affect your friend’s chances at becoming president.

So perhaps this $150,000 isn’t just for the affair story? Maybe it’s payment in advance to write a few health and beauty columns for your gossip magazines later in the year?

(Columns which can then be reprinted, almost word-for-word, across AMI’s other titles…)

Or maybe its a fee to pose on the cover of the Spring 2017 edition of Muscle & Fitness Hers?

Or maybe there’s other stories that are useful to the Enquirer, or Star, or Globe? Karen was a Playboy playmate after all. She’s bound to have something juicy they can run.

Naturally you’d arrange her employment contract in such a way that means she could be sued if she ever tries to talk to any other publications about her alleged affair – but the money? Why, that’s just for her services as a writer and model!

If you think that sounds like a reach, it really isn’t. David Pecker admitted as much in the New Yorker. Explaining the condition he put on Karen McDougal’s employment: “Once she’s part of the company, then on the outside she can’t be bashing Trump and American Media.”

It’s a neat way to keep people loyal: employing them, instead of paying them off. It seems to work too.

One year on from the deal being struck, Karen McDougal currently lists her job as being a “Model/Fitness Mag Cover Girl, OK/Star Magazine & Radar Online Columnist”.

OK!, Star and Radar Online are all property of American Media Inc. As are a number of fitness mags.

Funny how these things work out.

In Part Four…

This might all feel like an excessive amount of background detail for what is, essentially, the story of a single cancelled booking at Mar-A-Lago.

You may even have forgotten that that’s what started this whole thing off: that the non-profit philanthropic organisation Leaders In Further Education chose to relocate their annual fundraiser soirée in light of Donald Trump’s bungled denunciation of Nazis.

How on earth is that related to the sixty year tale of Mafia execution, Russian espionage, corporate consolidation, legal malpractice and model silencing that we’ve been spinning for you?

The good news is: we’re getting to that bit.

The bad news is: before we do, we’re going to have to revisit the gargantuan clusterfuck that was the 2016 US presidential election.

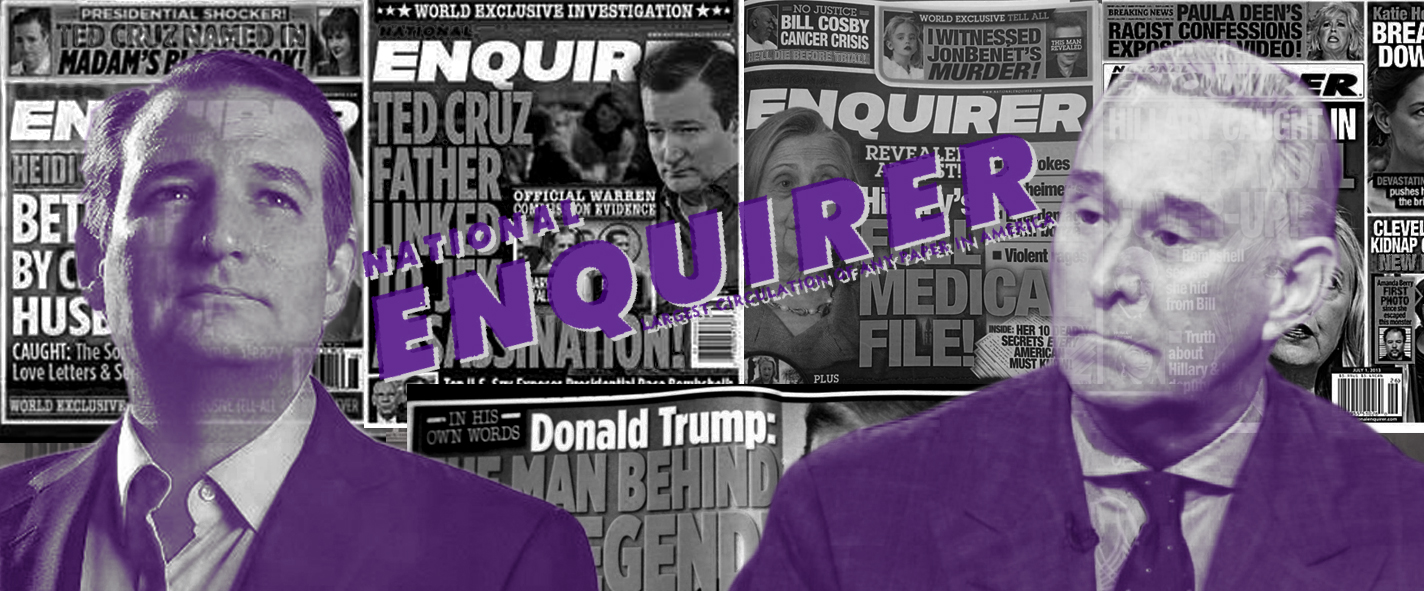

We’ll have to talk about the Republican primaries and the peculiar way in which the candidates were picked off, one by one. We’re going to have to talk about the Ratfucker of American Politics, Roger Stone. We’ll also have to briefly allude to Ted Cruz’s sex life.

Sadly, that can’t be helped.

However, once that’s all out of the way, everything should (hopefully) be in place to explain why that booking cancellation might yet prove to be the worst news that Donald Trump has had in a year of cataclysmically bad news. Whether or not that happens rests on the shoulders of one person: the CEO of LIFE.

And who is the CEO of LIFE?

You’ve met her already – you just might not have realised it…