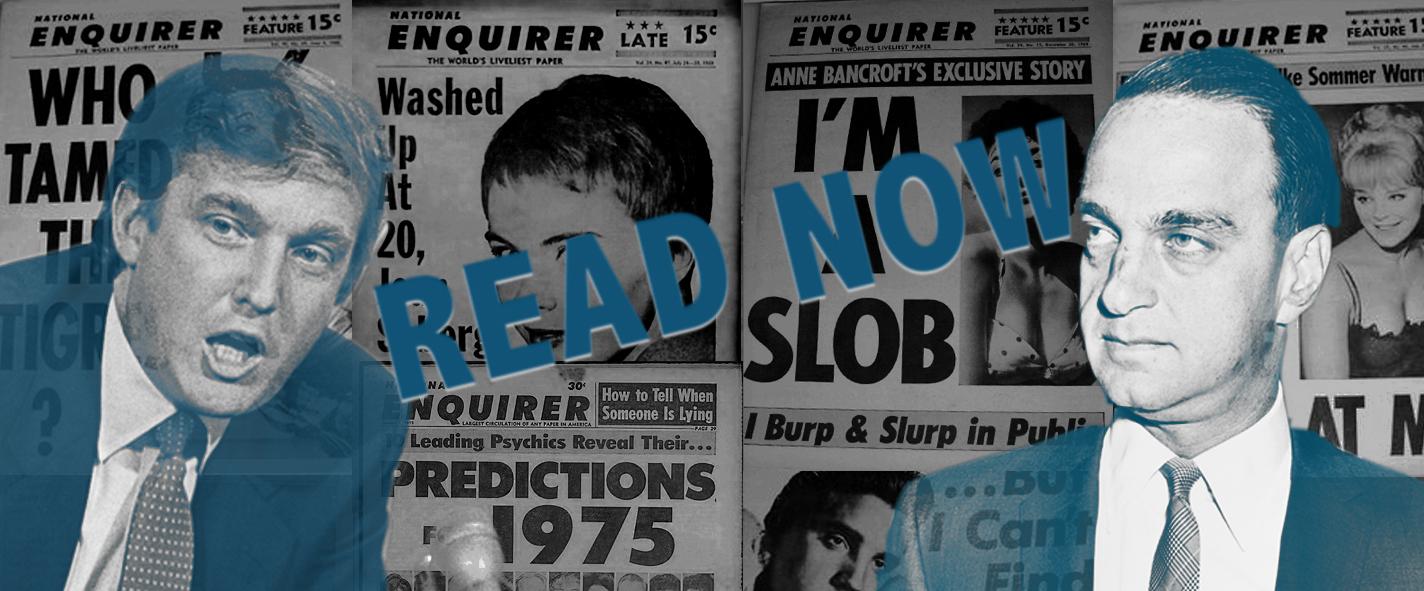

Our story starts with American Media Inc’s oldest and most notorious title: the National Enquirer. As the industry’s most sensational scandal rag, the Enquirer is often blamed for setting the grim tone of modern celebrity reporting – but how did it become so influential? And, more importantly, how did the Enquirer’s ties to a botched Mafia hit-job in 1950s New York end up causing a tabloid boom in 1970s small-town Florida?

I/ The Tabloid Triangle

Like many of the cheap, tawdry pleasures we enjoy today, the National Enquirer has its roots back in 1920s New York.

Like many of the cheap, tawdry pleasures we enjoy today, the National Enquirer has its roots back in 1920s New York.

It began life as the New York Evening Enquirer, a broadsheet newspaper that was very different to the death ’n’ divorce comic it would later become. Established in 1926, this early incarnation of the Enquirer was officially run by a man named William Griffin, but, in reality, the man pulling the strings was media mogul William Randolph Hearst (of the Hearst Corporation).

Hearst had stumped up the cash to start the paper on the condition that he would be able to use it as a testing ground to try out new ideas: the best of which he would pilfer for his other, better-selling publications; the worst of which got ditched.

He also liked to use the paper as a sort of secret bully pulpit: a cloaked backchannel to push his own agenda and address any personal vendettas he had (knowing that he wouldn’t be risking the Hearst empire if the Enquirer ever got sued – it would be Griffin’s neck on the line).

You may well think that an experimental trash-talking newspaper bankrolled by a shadowy millionaire with an axe to grind sounds like an absolutely dynamite publication – but the circulation figures tell a different story.

After 25 years of publishing, all the New York Evening Enquirer had to show for its efforts was a measly 17,000 readers. (To put that figure into context: 17,000 is roughly the current circulation of the Grimsby Telegraph and New York in 1950 was nearly 90 times the size of modern Grimsby).

The publication would almost certainly have been lost to history were it not for a new owner who came in, in 1952. A plucky 26 year old who changed the paper’s name, switched its outlook, and – in doing so – revolutionised the world of American tabloid journalism.

That new owner? Generoso Pope Junior – a.k.a Gene Pope, the Godfather Of Tabloid.

An Audience With The Pope

An Audience With The Pope

Gene Pope is undoubtedly the main character in this whole story but, for various reasons, he has taken a back seat in the history books to a number of better-known mob bosses, media moguls, power-mad politicians and all sorts of other egomaniacs.

Their names will ring bells of all shapes and sizes, yet were it not for the relatively unknown Gene Pope – and his determined graft in the background, throughout the 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s – a lot of what transpired in the 2016 US election might never have happened.

So who is he?

By every single account, Generoso Pope Junior was a man totally devoted to his work. A bright young student who graduated from MIT at the age of 19, who was snapped up by the CIA in his early 20s and who stood to inherit his choice of multi-million dollar businesses from his father – Gene Pope gave all of it up in order to follow a passion project of his own. A small, ridiculed tabloid printed on the shittiest paper available: America’s most notorious scandal rag, the National Enquirer.

We’ll delve a little deeper into how he managed to turn around the fortunes of an ailing regional paper and transform it into one of the biggest selling titles of the 20th Century shortly. For now though, we should explain the nickname.

Gene Pope became known as ‘The Godfather Of Tabloid’ because of the ruthless manner in which he ran his business (a common theme, you’ll soon discover…)

The Enquirer was a rank outsider in the world of journalism. A scrappy little underdog. An enfant terrible. Sneered at by the establishment and ridiculed by the well-to-do, the reporters who took jobs there quickly found themselves being black-listed by the rest of their profession. In fact, an Enquirer byline was such a shameful addition to a writer’s resumé that many of the reporters who did freelance work there would only ever do so under a pen-name.

Gene Pope was fully aware of this. He knew that what he was asking people to do was widely considered to be “dirty work”, and he knew that dirty work came at a premium. So, in order to entice the best journalists to work for him, he offered big incentives to mitigate the potential reputational risks.

Those who were loyal to him were rewarded handsomely. The Enquirer boasted huge salaries (way in excess of other journalists’), generous expense accounts, world travel opportunities and expansive medical coverage for their families.

Those who crossed him though – however minor the infraction – were cut loose and left for dead. One old Enquirer legend recounts the time that Gene Pope lost his shit so spectacularly that he tried to fire a guy simply for stepping into the office elevator ahead of him.

Turned out the guy wasn’t even an employee. He was the lunch delivery man.

It was these fiercely enforced notions of respect, honour and loyalty (combined with his infamous hair-trigger temper) that earned Gene his mobster moniker. They would also all be contributing factors in the creation of a huge pool of displaced, disgraced and out-of-work journalists that would begin floating around Florida twenty years down the line.

But these notions didn’t come from thin air. There’s a reason that Gene Pope ran the Enquirer like a Mafia don, and it’s probably helpful to know why – so let’s jump back a generation quickly and meet Gene’s father.

Daddy’s Boy

Daddy’s Boy

As the name suggests, Generoso Pope Junior’s father was Generoso Pope Senior – and Gene Senior’s story is as American as segregated apple pie.

He arrived on Ellis Island in 1906 as a 15 year old boy. 4,000 miles from home, a couple of dollars to his name and nowhere to stay, Gene Senior slept in a park that night. The next morning, he went looking for work.

He soon started work as a waterboy on a building site. In little over a decade, he would go on to take over the management of a construction company. In little over two, he would be the millionaire owner of Colonial Sand and Stone – the company which had the contracts to provide the concrete for the Rockefeller Centre.

Construction could have made Gene Senior all the money he could have ever possibly wanted, but he wasn’t interested in just cash. He had his eyes on power. He had his eyes on influence. So he began to diversify his portfolio.

Gene Senior started buying up media businesses – first taking over New York’s biggest Italian language newspaper Il Progresso Italo-Americano, then taking up a number of others in the American North East, including Il Bollettino della Sera, Il Courier d’America and L’Opinione, as well as the radio station WHOM.

If you’ve never owned four newspapers and one radio station, what usually happens next is that you find yourself being courted by politicians, all eager to get you (and your readers) onside. And, sure enough, once Gene Senior had the entire Italian-American vote eating from the palm of his hand, he quickly became a fixture at New York’s Tammany Hall. There, he used his significant influence to help swing elections in favour of select candidates at city, state, national – and even international – level.

(A quick aside: Seeing as how interfering in other country’s elections is very much en vogue right now, we should point out that this is nothing new. In fact, Generoso Pope Senior was thanked, personally, by President Harry Truman in 1948 for doing just that. Gene Senior orchestrated and oversaw a successful letter-writing campaign, getting the readers of his newspapers to write home to their families in Italy, convincing them not to vote any Communist parties into the Italian government. How much of the eventual result was down to Gene Senior’s intervention, we can’t be sure, but it was sufficiently influential to warrant a thumbs up from the White House.)

Now, you’re maybe seeing a couple of red flags here. A self-made Italian-American man. Owner of a concrete company. Media baron. Political kingmaker. Extremely tight ties to the home country. You’re thinking Mafia, aren’t you? Of course you are. It couldn’t be any more Mafia if it turned up to your daughter’s wedding and kissed you on both cheeks.

But Gene Senior wasn’t a mobster. He just had… connections. And the closest of them was to the man they called the Prime Minister of the Underworld, Frank Costello.

The Godfather’s Godfather

The Godfather’s Godfather

The name Frank Costello may not be immediately recognisable to you, but you will certainly know of his influence.

Fans of the movie will know that Vito Corleone from The Godfather is meant to be based on number of different New York mafia figures of the mid-20th Century. However, Frank Costello was supposedly the one that Marlon Brando used in order to develop his distinctive accent – mimicking tapes of Frank Costello’s testimony in the Kefauver hearings.

Quite how accurate Brando’s impression ended up being is a matter for another time. The point here is this: Frank Costello was a big deal in the New York Mafia. A really big deal.

To give you some idea of quite how big, “The Five Families” is the name given to the five major mob operations in New York. In 1938, Costello was installed as the head of the biggest, most powerful of those five – the Luciano family.

You probably don’t need telling that the Mafia is a pretty brutal business. It involves frequent, fatal changes in personnel. Yet, such was Frank Costello’s power, he managed to serve out two full decades as boss of the Luciano family before anyone dared fuck with him.

That’s a long time to stay in any role, whatever the industry. But when your work routinely involves blackmail, extortion, racketeering, bootlegging and contract killing, it’s practically an eternity. Tony Soprano made seven seasons. Frank Costello made twenty.

As well as being the figurative Godfather though, Costello was also a literal godfather… to Generoso Pope Junior.

Gene Senior had become good friends with Frank Costello – and it’s not hard to see why. You don’t stay at the top of an organised crime empire for twenty years if you don’t have a good concrete supplier, a sympathetic newspaper proprietor and a powerful political powerbroker somewhere in your orbit. And if those three people are one and the same – well, you’re going to find yourself spending a lot of time with that person. Best to have a good relationship.

Their friendship blossomed to such a degree that Gene Senior asked Frank to take care of his boy in the event that anything should ever happen to him, and Frank happily accepted.

Of course, if there’s one thing the Mafia takes seriously above anything else, it’s family – and Costello didn’t shirk from his responsibility. He kept a keen and watchful eye over Gene Junior throughout his life, but especially in 1950, when Gene Senior died and the rest of the Pope family began to turn their back on young Junior.

Gene Junior had very obviously been his father’s favourite, much to the annoyance of his mother and two older brothers. As soon as Gene Senior snuffed it, the resentments started to spill over almost immediately.

Junior was frozen out. Not just socially. Professionally and financially too. His mother and two brothers kicked him out of his job at Gene Senior’s paper, Il Progresso, and effectively disinherited him from the Pope family fortune – purely out of spite.

With no job, no real source of income, a wife to support and a baby on the way, Gene Junior quickly found himself on the bones of his arse.

So he began hunting around for opportunities and, in 1952, he discovered the New York Evening Enquirer was up for sale. The only problem was that he had no money.

With no access to the Pope family millions, he would struggle to meet even the most meagre asking price. Luckily for him, he had someone to turn to. His spiritual guardian and moral mentor, Frank Costello.

Acquiring The Enquirer

Acquiring The Enquirer

There’s a story that Gene Junior liked to tell about his acquisition of the Enquirer. He claimed that he was so broke when he bought it he had to spend his very last dollar on the cab ride to get him to their offices in time to finalise the sale.

Given his talent for sensationalist horseshit, this was likely an exaggeration – but, like so many National Enquirer stories, it has just enough truth in it not to be a total lie.

The exact details of the Enquirer buyout are pretty opaque (which isn’t a surprise, given the agents in play) but most reports suggest that Gene Pope picked the paper up off William Griffin for $75,000. Obviously this was much more than Gene could personally stretch to, given that he barely had a enough to pay his taxi driver, but Gene had backers. Two to be precise.

One of them (who we’ll deal with in Part Two) was Roy Cohn – an attorney and childhood friend.

But his main benefactor? Head of the Luciano crime family, Prime Minister of the Underworld and inspiration for the actual fucking Godfather. Frank Costello.

Exactly how Costello, Cohn and Pope split the tab is unclear – but that $75K was only the start.

Scraping together the cash to buy a newspaper is merely the first financial hurdle in a series of many. And if Gene’s last dollar really did go on cab fare, where did he find the money to hire staff to write his stories? Where’s the money to rent them office space? The money to order a print run?

You’ve probably figured out the answer – but let us tell you anyway.

It came from Frank Costello. Which means it came from the Mafia. Week after week, Gene Pope would take out a short-term loan from Costello in order to meet his immediate staffing and production costs. Then, once the issue’s revenue had been collected from newsstands at the end of each week, Gene would send out a reporter to the Waldorf-Astoria to hand a cash-stuffed envelope over to one of Costello’s associates – payment with interest. And it worked that way for years as the Enquirer was trying to find its footing.

As anyone who has ever taken mob money will tell you, it doesn’t come without conditions. Luckily, for family, Costello’s were relatively tame. All he wanted in return for his investment, as well as being paid back on time, was for the Enquirer to steer well clear of any Mafia or Mafia-adjacent stories.

There are few things to really light a fire up under a person quite like a Mafia deadline, and Gene Pope – to his credit – flourished under the pressure. It wasn’t easy, and he would constantly complain that he was having to borrow from one guy to pay off another, but he managed to keep the lights on and the printing presses rolling.

Over the coming years, the National Enquirer would steadily build up its circulation with its arresting mix of gore and gee-whizz stories – rising from a pitiful 17,000 at the time of the takeover to a solid million by the mid-sixties and reaching a peak of over 6.4 million in the mid-seventies.

Which is all very well. But how does any of this New York mafia stuff explain why a celebrity journalism boom occurred in small-town Florida – some 1,200 miles away and twenty years later?

Hit And Run

Hit And Run

Fve years after he had helped Gene Pope acquire the National Enquirer, Frank Costello had to take something of a back seat in running New York’s biggest organised crime syndicate in 1957, on account of being shot in the back of the head.

He survived the shot. Frank’s would-be assassin, like a villain in the movies, had tried to send him off with a snippy parting word – but, in saying “THIS ONE’S FOR YOU, FRANK!” he caused Costello to duck just in the nick of time, resulting in mainly superficial injuries to his scalp.

By this point, the Enquirer was on the up and wasn’t relying so heavily on Costello’s support. The pair were still extremely close (Gene had been dining and drinking with Frank less than an hour before the shot) but now someone else was in charge.

And once the claws of the criminal underworld are in you, they aren’t so easy to extract.

In the late 60s and early 70s, the Enquirer developed a bit of a distribution problem. As soon as they started ordering print-runs of a million-plus, certain mysterious forces decided to start taking advantage of the Enquirer’s popularity.

Someone – whether it was official Five Families business, or whether it was a gang of off-brand thugs – was breaking into the Enquirer’s printing press and running off 30,000 extra pirate copies each week. Rather than sell them though, they would load these extra copies back into the delivery trucks that were returning to Enquirer HQ and pretend that they were unsold copies. This would then allow someone, somewhere in the distribution chain, to pocket the sales money for 30,000 copies without anyone noticing a shortfall on the books.

Quite how long they got away with this ruse is unclear, but at some point Gene Pope began to smell a rat. So he set up a small investigation of his own. What happened horrified him.

He hired a former associate, Angie La Pastornia, to ride along in the back of one of his delivery trucks, so that Angie could keep an eye on what was going on to see if anything untoward was happening in distribution.

And something was. But rather than ditch their plan when they were caught in the act by Pope’s spy, they decided to improvise instead. The delivery truck was returned to the Enquirer’s offices with Angie La Pastornia bundled in the back, dead, with a note pinned to his chest by a knife.

There appears to be some disagreement between reports as to what the note actually said, so why not pick your favourite? You have a choice of the simple-yet-brutal “FUCK OFF” or the quietly-more-menacing “DON’T FUCK WITH US”.

Still, whatever the exact wording was, the broader message was clear.

Unsurprisingly, it was shortly after that incident that Gene Pope started to explore real estate opportunities in Florida.

Pope uprooted his entire life and enacted something of a midnight dash. He moved his entire publishing operation down to Lantana, a small town in Palm Beach County, helpfully putting some 1,200 miles between him and whichever shady force was stabbing his staff and stealing his product.

The decision to follow him was a relatively easy one for his staff, hooked – as they were – to their huge salaries. For not only would they be unable to find another job that paid anywhere near as well, they would be unable to find another job full stop, tarred by their association with the Enquirer.

So, like the Pied Piper in a witness protection program, Gene Pope led his entire staff down to Lantana, FL. But his staff weren’t the only ones who followed him.

The National Enquirer had become such a success at this point that it had spawned a number of imitators. Publications like the Globe, the National Examiner, the Sun had all been trying to replicate the Enquirer’s success, and now – in the early 70s – some of the big hitters were stepping up to try their hands at it too.

Rupert Murdoch created Star Magazine. The New York Times Company started up Us Weekly. Time Inc brought out People.

The downmarket tabloid was thriving, and thanks to Gene Pope’s habit of firing up to half of his newsroom in any given week – sending scores and scores of otherwise-unemployable cutthroat reporters out onto the streets of Florida, with nowhere to go and nothing else to do but drink their savings and soak up the sun – there was a huge pool of journalists with which to staff them.

So a bunch of competitors set up shop nearby in Florida, creating a thirty mile area around the National Enquirer which would later become known as the Tabloid Triangle. And would later still become home to the company which then tried to buy all these competitors up, and consolidate the entire tabloid market into one big company: American Media, Inc.

An Unexpected Move

An Unexpected Move

The reason why this move to Florida – of all places – was so significant wouldn’t become apparent until about 11pm Eastern Standard Time on November 6th 2016, when Florida announced its election result.

About 15 minutes along the coast from the Enquirer’s Lantana offices (10, if the traffic’s good) stands a rather grand building on the coast of Palm Beach. Built by the millionaire philanthropist, Majorie Merriweather Post, she gifted the property to the federal government shortly before her death in the hopes that future Presidents would come to use it as a southern retreat.

A sort of “Winter White House”, was how she billed it.

The National Parks Service gladly accepted the gift, but – through no real fault of their own – future Presidents just didn’t take to it. After President Nixon and President Carter both opted to stay in other locations when taking trips to the south, the federal government decided they just couldn’t justify the multi-million dollar upkeep of the property. Especially if Presidents weren’t going to use it. So they returned it to Post’s daughters who put it on the market.

After some extremely devious deal-making, the property was bought in 1985 by a private citizen, who still happens to be the current owner.

That building? Mar-a-Lago.

And the owner? Donald J Trump, president of the United States of America.

In Part Two…

In Part Two…

While all of this was happening on the one side, there was another story happening in tandem. One regarding Gene Pope’s other major backer – Roy Cohn.

Cohn would prove to be just as significant an influence on this whole story as Frank Costello, ensuring that lowbrow celebrity gossip had an impact on the highest, most reputable offices of the land.

So before we get too settled in Florida, we need to take a trip back in time to 1950s New York again and trace a second, parallel path to this one – to see how the Enquirer came to hold any political clout.

And, in turn, we’ll discover how a disgraced lawyer who made his name executing Soviet spies (American citizens who handed the Russians highly classified military intelligence) accidentally set the stage for Donald Trump to assume the presidency – and accidentally do the exact same thing…