The rise of “structured reality” shows, where producers consciously create drama and script scenes rather than strictly document real life, has arguably caused us to lose our grip on actual reality – but, in doing so, we might be getting a clearer picture of how the world really works…

III/ Surreal World

We have spoken at length about Hulk Hogan’s penis before but, if you’ll indulge us one last time, we have cause to briefly touch on it again.

We have spoken at length about Hulk Hogan’s penis before but, if you’ll indulge us one last time, we have cause to briefly touch on it again.

During the now-infamous court case in which he bankrupted the gossip site Gawker for publishing his sex tape, Hulk Hogan was asked about the size of his penis under oath. It might sound stupid, but the answer he gave in that Florida courtroom may well be one of the most significant cultural moments of the 21st century to date.

Because Hulk Hogan claimed to have two penises.

Not two physical penises, you understand. One was his actual, real-world Terry Bollea penis; the other was his conceptual, fictional Hulk Hogan showpiece.

These two penises, he maintained, were very different beasts. Hulk Hogan might have bragged about having a ten-inch whopper on stage and in interviews, but that wasn’t Terry Bollea’s penis he was talking about. No, sir. That was not his penis at all.

Hogan (or, rather, Bollea) was very keen to stress this point, repeatedly stating “I do not have a ten-inch penis […] I do not. Believe that. Seriously […] Terry Bollea’s penis is not ten inches.”

The reason he wanted to make this double-dick-size point crystal clear was because one of Gawker’s major arguments was that Hulk Hogan had made at least part of his multi-million dollar fortune from bragging about his bulge, so it was therefore up for journalistic scrutiny.

Gawker also argued that Hogan clearly didn’t have any qualms about privacy when he agreed to have cameras film him, pants around ankles, farting and shitting into his toilet as part of his VH1 reality show, Hogan Knows Best.

To which his response was, essentially: yes, but he had been farting and shitting in character – as Hulk Hogan. The sex tape that showed him banging his best friend’s wife though? That, he was doing purely in his capacity as Terry Bollea – and it’s therefore a totally different thing.

This sort of ‘deep character’ defence is extremely en vogue at the moment.

Daniel O’Reilly – who got hauled over the coals a few years back for “creating a rapist’s almanac” with his short-lived reality show, Dapper Laughs On The Pull – famously went on Newsnight in a solemn black turtleneck to explain that he hadn’t been making those jokes himself. It was all just a character.

Paris Hilton decided to come clean recently – about a decade after her show had stopped airing – confessing that she’d actually been playing a ditzy airhead character on The Simple Life all along. If people had somehow got the impression that she was a spoilt socialite, well, that’s only because she was a great actor who took her roles very seriously.

Donald Trump used it too. During the 2016 campaign, he was asked about the demeaning and derogatory comments he frequently made about women. He had a very simple explanation for it.

“A lot of that was done for the purpose of entertainment […] You know, you’re in the entertainment business. You’re doing The Apprentice. You have one of the top shows on television. And you say things differently for a reason.”

He didn’t say those things as Donald Trump, the man! He said those things as Donald Trump, the IMDB credit!

This explanation is always offered up as if it is totally self-evident, and the people who trot it out always seem to be astonished that there could have been any confusion about it all.

Rest assured, this is not because Hulk Hogan, Dapper Laughs, Paris Hilton and Donald Trump are operating on some higher intellectual plane than the rest of us, able to comprehend things way beyond our mortal ken.

The confusion exists because reality TV – something of which all these people are a product – has thrown a fucking great smoke grenade into the middle of the media landscape, obscuring everything that once seemed fairly clear to us.

Over the last few years, it’s become plain that we no longer have a shared consensus on what is real and what is fake. How did we end up in that situation? How did that help someone like Trump parlay his pop culture fame into genuine political power? And what does any of this have to do with the survivors of the Parkland shooting?

We’re getting there, we promise – but it takes a bit of explaining. Thankfully, we’ve got a visual aid to help us through this next bit.

Entering The Matrix

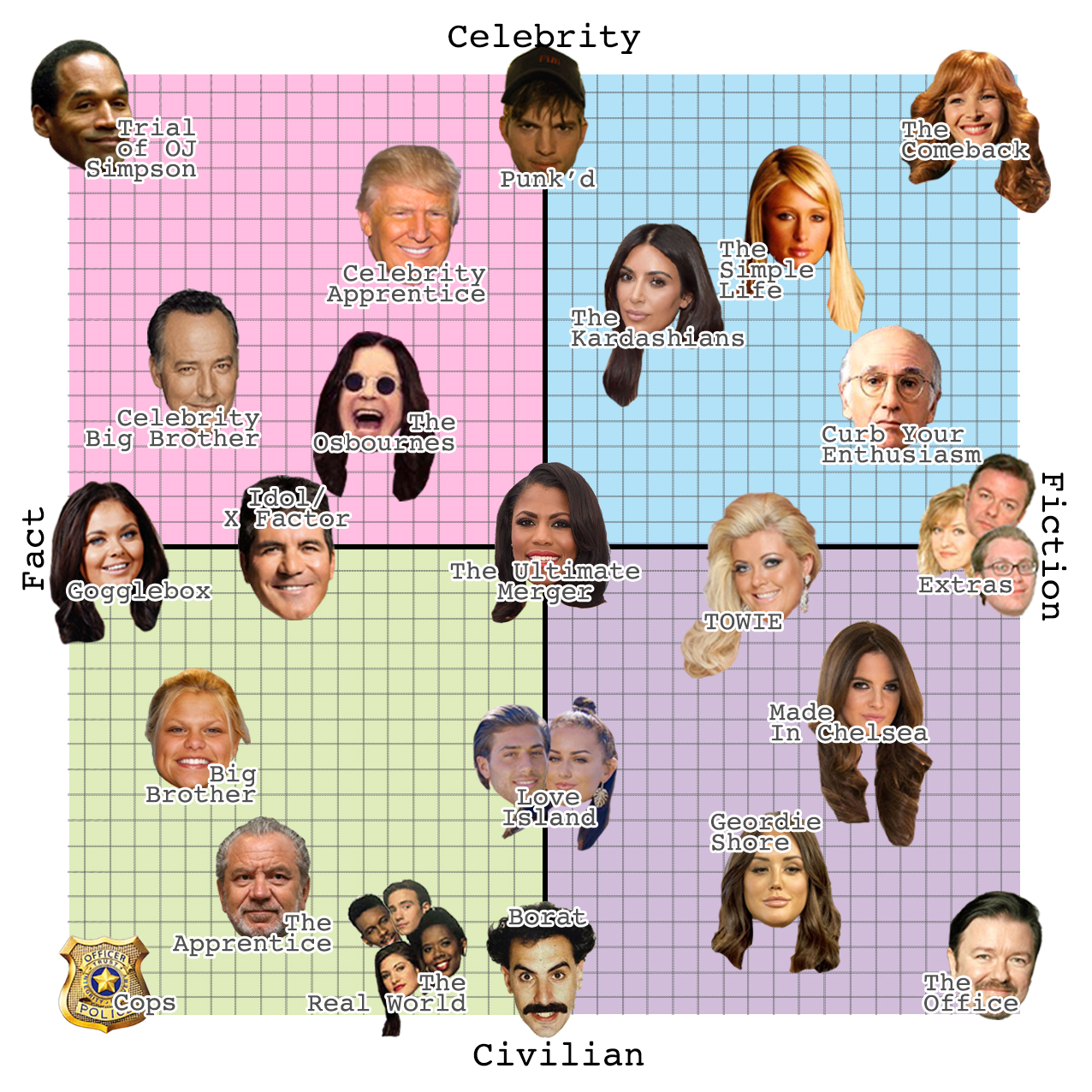

Because so much of what follows happened all at once, there’s not really any simple linear route through it. In order to deal with it as quickly and efficiently as we can then, we’ve drawn up a graph and plotted a number of significant reality (or reality-based) shows across the two different axes: Fact/Fiction and Celebrity/Civilian.

As reality TV has evolved and adapted, these two axes have gradually been folding in on each other, leaving us floating around a messy centre-point, somewhere between these four states.

The examples we’ve picked are not intended to be exhaustive, merely illustrative – so let’s dump this graphic down and start walking you through it.

Axis One: Celebrity-Civilian

Axis One: Celebrity-Civilian

Reality TV has become the great celebrity leveller: elevating and venerating the common man; grounding and humanising the superstar.

It has given a platform for regular citizens to enjoy fame just for being ‘real’, while simultaneously giving celebrities a more personal, more relatable charm to their otherwise other-worldly existence.

How did that come about? Here’s a quick sprint through the major plot points.

The Trial Of OJ Simpson (1994/95)

We mentioned in Part One that when Cops was being pitched around the various networks throughout the 80s, one of the executives’ major concerns was that, without a star name attached to the project to host or narrate, no-one was going to be interested in watching it.

The 30 seasons of Cops that have since aired (and the hundreds of reality series that followed in its wake) proved that viewers are only too happy to watch everyday people on TV, but the network execs hadn’t been entirely wrong – something they’d come to realise on 17th June 1994.

That evening, the Big Three networks and CNN suspended their scheduled programming to cut to live footage of a police chase that was happening in Orange County, California. Like an impromptu episode of Cops, a fleet of police cars and a swarm of helicopters were all in hot pursuit of a white Ford Bronco driving along I-405, and they were bringing the viewing public at home along for the ride.

In the back of that white Ford Bronco, fleeing the law, holding a gun to his own head? OJ Simpson.

OJ was brought safely into custody, and the entire ordeal – from police chase to televised trial – became a global sensation. Sordid and unseemly though it might have been to spectate on a real-life murder trial, there was something about watching a famous athlete being treated like a common criminal that was catnip to viewers.

While there haven’t been many more star suspects up on counts of double homicide since, the format of transplanting celebrities into other ‘civilian’ situations would turn out to be infinitely replicable.

Popstars (1999/2000)

On the other side of the celebrity/civilian spectrum, a new strain of reality talent competitions would start springing up all around the world. First Popstars. Then Pop/American Idol. Then The X Factor, Got Talent, The Voice. These shows were all specifically designed to take regular, ordinary people and turn them into The Next Big Thing.

It’s a solid format, and ot’s produced some hugely successful stars, but there’s only so many hours of plain old karaoke that an audience can stomach. So, in order to keep viewers coming back week after week, they introduced two crucial elements into the mix.

The first was contestant back-stories. Through a series of backstage interviews, we would learn more about the people who were singing for us, developing the human interest angle and creating series-long storylines for viewers to follow.

The second was interactive televoting. Not only did this offer viewers at home a chance to participate in the way the show progressed, it gave them the opportunity to override the opinion of the expert panel of judges. If viewers felt that Simon Cowell didn’t know what the fuck he was talking about when it came to their favourite act, they could gather together in their thousands and use their vote to stick it to him.

The Osbournes (2002)

Further proof that the celebrity/civilian divide was crumbling came in the form of The Osbournes: a reality documentary show that turned the idea of making a regular person famous on its head, by taking someone incredibly famous (Ozzy Osbourne) and showing his everyday domestic routine.

It was weird to see one of heavy metal’s most recognisable legends shuffling about his mansion, swearing at the dogs for shitting everywhere, and screaming for his wife because he couldn’t work the oven – but the combination clearly worked. The Osbournes quickly became MTV’s most-watched show of all time.

As well as showing the utterly mundane side of celebrity life, it also turned his lesser-known family members into fully fledged celebrities in their own right. Sharon Osbourne went from being a music industry figure to mainstream personality – getting her own chat show and long-standing jobs as a judge on America’s Got Talent and X Factor – while his kids, Kelly and Jack, started presenting and pop careers of their own.

Keeping Up With The Kardashians (2007)

The Osbournes was the very show that Ryan Seacrest had in mind when he started up conversations with Kris Kardashian about ways that his new production company could create a reality TV format featuring her family.

The Kardashian name had first become famous thanks to Robert Kardashian, who had gained exposure as a friend of (and legal representative for) OJ Simpson throughout his trial – but his kids had started cropping up on reality TV shows too on the strength of the Kardashian name. Kourtney had been picked to appear on the rich-kids-doing-grunt-work show Filthy Rich: Cattle Drive, while Kim had been popping up as Paris Hilton’s assistant on the original famous-family/rich-daughter show, The Simple Life.

You probably don’t need telling how phenomenally popular the series has been. The Kardashians have since become some of the biggest names on the planet – the epitome of “famous for being famous”.

Kim Kardashian might well be the best example of someone gaining megastar status through reality TV, but the individual who best personifies the peculiar and very particular quantum state that reality TV has created – of somehow being both celebrity and civilian simultaneously, while also managing to be neither – isn’t a Kardashian.

It’s Omarosa Manigault.

Fire Hazard

Like Steppenwolf were born to be wild and Craig David was born to do it, Omarosa was born to do one thing: get fired.

Somehow, she has managed to turn the process of losing jobs into a career and has made quite the name for herself out of the fact that she is manifestly unemployable.

Her career began as a political consultant, working in various capacities at the White House for the Clinton administration. According to former colleagues there, she was not well-liked, nor was she particularly good at anything – which is why she ended up being bumped around four different jobs in the two years she was there.

Prone to arguments, unable to work as part of a team and hopeless with responsibility: these attributes may not be hugely conducive to a happy office atmosphere, but they’re absolutely perfect for The Apprentice – which is where she ended up.

Omarosa made such a splash in that first season that she quickly became the series’ break-out star, despite getting fired in episode nine.

Her profile grew so much that she was invited back to join actual, bona fide celebrities on the first season of The Celebrity Apprentice in 2007; and then again on The All-Star Celebrity Apprentice in 2013 – making her the only person to appear on three separate seasons of the show.

This trajectory neatly demonstrates the celebrity opportunities for civilians in reality TV. But what did all of this exposure get her? Weirdly, a job right back where she started. As a public servant in the White House – a job from which Trump recently fired her for a record-breaking fourth time.

It was a fitting coda to this chapter in Omarosa’s career that her most prominent debrief interview upon leaving the White House occurred not on Meet The Press or Face The Nation or 60 Minutes like you’d maybe expect, but on Celebrity Big Brother.

However, the moment in Omarosa’s reality career that is most notable for our purposes is her own vehicle: the Apprentice spin-off show that Trump created for her in 2010 – The Ultimate Merger.

The Ultimate Merger was an Apprentice-themed take on The Bachelorette, in which Donald Trump – that most discerning of matchmakers – picked 12 men who he thought would make good marriage material for Omarosa. Then, over the course of eight episodes, Omarosa would eliminate these potential matches until she was left with one.

It was not a groundbreaking idea for a show, nor was it especially well-made or received. So what makes it so interesting?

The whole thing was a massive fucking hoax; a completely fabricated conceit in order to produce and broadcast eight episodes of television and net everyone involved a nice pay packet.

The ‘winner’ was revealed in the season finale to have been legally married (albeit separated) all along, which was considered to be a breach of the show’s rules – something you’d have thought a more legitimate production might have checked before the closing credits were set to roll.

The winner was disqualified, leaving Omarosa with… no-one. That’s it, folks! Show’s over!

Omarosa, for her part, wasn’t even trying to hide the fact that the entire show was a scam, and proceeded to not-so-secretly date someone else (the actor Michael Clarke Duncan) throughout the show’s broadcast run.

From top to tail, The Ultimate Merger was a grift. A wholly structured TV show that was masquerading as reality.

Which brings us back to our second axis.

Axis Two: Fact V Fiction

Axis Two: Fact V Fiction

The many fictional elements involved in producing reality TV are well-documented . You probably already know all about how footage and reaction shots and soundtracking and editing are used to guide and manipulate viewer responses – so we needn’t reheat any of that here.

However, there’s something interesting to point out in how fictional television has both adopted and informed the tropes of reality TV. We’ll blitz through it quickly.

The Real World (1991)

Before commissioning executives caught wise to the fact that celebrities-in-a-civilian-setting was ratings dynamite, the lesson they’d initially taken from Cops’ success was that getting regular people on screen was cheap and easy to do. So they started commissioning shows that featured total nobodies – the first of note being MTV’s The Real World.

The premise was as simple as Cops’: seven ordinary people would be brought together to share an apartment and let cameras follow them around everywhere. There were, however, two major complications in translating the Cops format.

The first was that the action taking place in Cops was fairly easy to follow without any commentary (see bad guy; chase bad guy; catch bad guy), but because so much of The Real World relied on interpersonal politics, it was crying out for some narration.

Which is where the idea of the confessional talking-head interview came in, with producers interviewing participants one-on-one to get their explicit opinions about what they thought was happening. Hundreds of reality shows since The Real World have involved some element of this – be it a diary room, backstage interviews, a spin-off analysis show – and this, much like televoting, would come to have a big effect on the wider culture.

The other problem was that, while Cops dealt with the inherently exciting topic of crime and punishment, it quickly became clear that regular people, left to their own devices, might choose to avoid conflict and try to live as quiet a life as possible. To keep the drama ticking over, producers would often step in to stir up a fight or create a bit of conflict, ensuring they had something juicy to film.

It’s a sneaky move, but their defence was that although it may not strictly be ‘real’ (insofar as the wider situation had been contrived) the responses and reactions being filmed were real. And that was close enough.

Curb Your Enthusiasm (2000)

While it had long been common for sitcom leads to play a fictional version of themselves, Curb Your Enthusiasm was slightly different. As well as the show’s (initially non-celebrity) creator Larry David playing an unflatteringly-fictional version of himself, the show wasn’t scripted either. At least not in any traditional sense.

To give the show a greater sense of ‘reality’, David would meticulously work out the plot of an episode, give his actors a rough sense of what each scene needed to achieve, then had them improvise the dialogue and recorded the results.

The show was a real critical darling, and this semi-improvised method would not only be picked up by other sitcoms attempting to closely emulate natural dialogue (Reno 911!, The Thick Of It, Veep, The Trip) but also structured reality shows themselves like The Hills, Made In Chelsea, The Only Way Is Essex and Jersey/Geordie Shore.

The Office (2001)

By the turn of the century, so many docusoaps had been filmed and broadcast that the tropes of reality TV were well-known enough to be parodied. The Office wasn’t the first mockumentary comedy, but it has definitely been one of the most influential.

The Office’s roving hand-held cameras and lapel mics managed to ‘catch’ moments that the show’s protagonists didn’t realise were being filmed, allowing the audience to see the ‘real’ story. Obviously the entire thing was scripted but the characters would address the cameras – and camera crew – directly, pull faces, make glances and generally break the fourth wall in a way that we’d come to expect from reality TV, but not a scripted sitcom.

The format was so popular that it has since been imitated countless times. So much so that the ‘reality mockumentary’ sitcom no longer needs any setting up as a narrative device. Shows like Parks And Recreation or Modern Family feature all the same sorts of talking head interviews, covert filming and reactions directly to the camera, which belie the ‘real’ story – but without offering any explanation or acknowledgement that a documentary is being filmed. This is just a framework that audiences instinctively recognise.

And it’s this same framework that’s key to understanding the whole problem.

The Hot Mic Moment

The Hot Mic Moment

While making a campaign visit to Rochdale in advance of the General Election in 2010, then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown was introduced to a local woman, Gillian Duffy.

The Brown-Duffy beef is well known, but to quickly recap: Duffy had been heckling Brown while he was trying to give an interview on live TV. When it became clear that Brown wasn’t going to be able to ignore her, he engaged her in conversation. Duffy wanted to talk to him about immigration.

Their chat was amiable enough in front of the cameras, and ended with Brown giving her a pat on the back, complimenting her family and telling her that it had been good to see her. But the instant his car door slammed shut, Gordon Brown started complaining. He said it was a “disaster” that he had been put anywhere near here and called her a “bigoted old woman”.

The whole thing was caught on the microphone he’d been wearing. He’d been busted.

Obviously Gordon Brown wasn’t the first politician to be caught on a hot mic saying something unwise, nor would he be the last.

Mitt Romney was caught on covert camera saying that there was 47% of the country that was never going to vote for him and so, essentially, fuck those people. It was disastrous for his campaign. Not because he was wrong about it necessarily, but because it’s what everyone suspected he’d been thinking all along and wasn’t actually saying.

In an unwise moment of candour, Hillary Clinton spoke of the Trump voters she considered to be a “basket of deplorables”. Her detractors knew she secretly held them in disdain, but with that comment she’d gone and let the mask slip. This was the real Hillary Clinton. The rest was a character.

Of course, we’d always known that politicians thought these sorts of things. Occasionally it would be confirmed too. But in the modern media landscape – where everyone we watch is playing a game, putting on a show for the cameras, and keeping their true opinions secret until the moment that they’re alone backstage – we knew all too well what this was.

When we saw Gillian Duffy react to the news that Gordon Brown had slagged her off in the diary room, it was clear that these two games were the same.

‘Structured reality’ wasn’t actually all that different from actual reality.

All these moments caused mortal damage to their respective campaigns. So what made Trump’s pussy-grabbing hot mic moment so different?

By the point that the Access Hollywood tape emerged, Donald Trump had already said a number of outrageous and offensive things, including:

– Calling Mexicans rapists and murderers

– Doing an impression of a disabled reporter

– Suggesting someone should assassinate Hillary Clinton

– Bragging about being able to commit murder without any consequence

– Telling security to “beat the hell” out of protestors at his rallies

In that context, the pussy grabbing comments made complete sense. There was no mask slipping. There was no dissonance. The only surprising thing about Trump saying that he frequently sexually assaulted women was that he didn’t do it from the podium at one of his rallies.

It probably says horrendous things about us as a culture that we can easily turn a blind eye to this sort of thing if its broadly in keeping with someone’s outward character – but this appears to be the attribute that we currently pride above all others.

Not kindness. Not capability. Not even honesty (although we often mistake it for that). What we seem to crave more than anything is consistency.

And that’s not without good reason. Our once clear-cut notions of fact, fiction, expert, amateur, entertainer, politician – reality itself – are now so bent out of shape that they’re barely fit for purpose. When even David Attenborough is taking flak for tarting up his documentaries with doctored sound effects, it can often seem like every last fucker is trying to pull a fast one on us.

We’re all so eager not to be caught out by the tricks that the media plays on us each and every day that we’d rather tie our lot to a bad guy if we can be absolutely sure that they’re going to continue being a bad guy because at least you know where you stand with them, y’know?

This would appear to hold true even if they’re a documented fraudster. Even if they’re a suspected phone-hacker. Even if they have a stack of P45s as thick as War And Peace. So long as they’ve made it clear in advance that they’re an irredeemable piece of shit, we know -– whatever else – that they aren’t trying to pull the wool over our eyes.

This “any port in a storm” mentality is a deeply unhelpful response to the terrible situation we’ve found ourselves in.

The good news is that help might be on its way.

Generation Next

Generation Next

2018 is going to be a key year in determining the true extent of reality TV’s effect on our political discourse. Why? Because the children who turn 18 this year – and therefore become eligible to vote – were born in 2000.

The same year that Survivor first dominated the ratings.

This coming generation have known nothing but a post-Survivor, post-Big Brother, post-Idol world. The only frameworks and mechanisms through which they navigate media, news and the world in general have all been informed by reality television. It’s unavoidable. Even if they’re one of those square kids that grew up without a TV and read newspapers instead, this is the lens through which the whole world is seen now. They know nothing else.

Now they’re going to be able to vote. But unlike previous generations, they’re entering adulthood well practiced in the art of democracy.

For years they have been voting (with the permission of the person who pays the bill) to save their favourite act in Idol and Got Talent and X Factor. Not just once every four years. Week after week, season after season, year after year.

For years they have been actively encouraged by their favourite shows to become advocates for their chosen acts – organising to get them trending on Twitter, forming fandoms on Tumblr, signal-boosting them across Snapchat, Instagram, Facebook.

But, perhaps most critically of all, in having watched hundreds of hours of this sort of stuff over their formative years, they have become incredibly adept at spotting the way that these shows work. They’ve seen how media narratives get framed, how producers can edit things to make people look virtuous or villainous. They have grown up with broadcast quality cameras in the pockets, and have been creating and curating their own personal brands across social media almost as long as even the most seasoned adult.

They were born on this battlefield – and now they’re coming for Trump.

The children of Broward County, Florida – specifically, the survivors of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High shooting, who organised last weekend’s March For Our Lives – were all born after reality TV started topping the end of year ratings. It’s highly likely that not a single one of them formed any meaningful conscious memory before the first season of The Apprentice aired.

Yet far from growing up to become the braindead, vapid reality junkies that everyone prophesied we were breeding, from what we’ve seen so far, they appear to be standing at the front of a new generation of savvy, sophisticated pop culture activists – all of who are primed to flourish in the current political atmosphere.

And this, in no small part, is why a certain air of suspicion has gathered around them.

The Infotainer

The Infotainer

There’s one final person of note who used the Hulk Hogan Ten Inches defence recently. Someone else who claimed that the things that he’s said and done in the public domain were all the work of a character. A character who might have shared his name, likeness and social security number – but was, in fact, a totally different man.

InfoWars’ Alex Jones.

Last year, while in court fighting for custody of his kids, Jones’s lawyers tried to reassure the judge that whatever she might have seen on InfoWars – whether it was him barking about Hillary Clinton being a literal sulphur-breathing lizard demon from Hell; or twisting on about how the grieving parents of the murdered Sandy Hook children were actors paid by Western Funding – it’s all part of an act.

His vein-popping, gruff-throated, spit-flecked rhetoric is merely ‘performance art’. It’s done for the cameras.

(Curiously, one of the clips that his ex-wife tried to enter into evidence was footage of Jones, in Washington DC on the night of Trump’s inauguration, drunk and hollering that “1776 will commence again” – the exact same line that he’d barked at Piers Morgan in that fateful CNN interview – before wandering off to piss on a tree. So the character obviously runs deep.)

None of this would matter very much if InfoWars was considered by everyone to be an entertainment show, and Alex Jones merely its enigmatic host. But not everyone does. Some people think that InfoWars is the only news organisation that’s reporting the real truth. And it’s not just a bunch of cranks and wingnuts in their Montana apocalypse bunkers. InfoWars was given press credentials for the White House.

In and of itself, this isn’t necessarily a sign that the sky is falling in. There’s a good argument to be made for letting InfoWars – or any other citizen journalist – into the White House Briefing Room, as it shouldn’t be for the state to decide who is and who isn’t considered a legitimate news source.

The only trouble is, this White House is doing exactly that – decrying CNN as ‘fake news’ on the one hand, while giving an internet show that broadcasts Sandy Hook denial ‘performance art’ a press pass.

If this blending of fact and fiction was simply confined to entertainment, it would be one thing – but it isn’t. It’s bled over into news, media and politics. Jeff Zucker’s shift from NBC Entertainment to CNN is the mainstream face of that problem; Alex Jones trying to push the story that the survivors of the Stoneman Douglas shooting are crisis actors is the shadowy masked face of it.

Jones claims that the Parkland kids seem suspiciously comfortable on camera, that they’re all off-book with all their talking points and that they’ve somehow managed to assemble and activate a huge movement across the country at a moment’s notice.

But could it be – could it possibly be – that the first generation to come of age in this post-Survivor age are uniquely adapted to thrive in this absolutely fucked-up culture we’ve managed to lose control of?

We’ll consider the case for it in Part Four…