After helping get Popbitch off the ground Neil Stevenson went off to edit the legendary style magazine, The Face. When things didn’t quite go to plan there he decided to write a novel about it. Twelve years later, he realised that hadn’t gone to plan either. So he wrote an article about how not to write a novel instead.

The Perils of Celebrity Murder Fiction

During the early 2000s, I spent several years as the editor-in-chief of a famous British style magazine called The Face. It was the best thing ever, and also a total nightmare.

It was wonderful because I had an access-all-areas pass to the worlds of celebrity and fashion. I visited famous bands in their studios. I watched the hottest photographers snap the hottest people. I sat in the front row of fashion shows and watched supermodels parade past as rose petals rained down from the ceiling, and then went backstage and drank champagne with the designers. Fancy, huh?

However it was a nightmare because, while under my leadership, the 25 year-old magazine closed. Sure, the circulation had been in decline for years, and the rise of the internet probably meant that its time was up. But I still felt like the guy who was given a vintage Ferrari to look after, and then wrapped it around a lamp post.

I dealt with my sense of failure in a traditional British fashion — by sitting in pubs and drinking beer — but one of the things I found hardest was to tell stories about my experiences. That time when we tried to photograph Beyoncé naked in a fiberglass banana split and she walked off set… was that a hilarious anecdote, or a huge mistake that contributed to the magazine’s demise?

This mental struggle continued for several weeks, until one day I had a brilliant vision. I would write a novel. It would feature all the most memorable moments of my time at The Face, reframed into a form that would entertain people, and also give me a new career. I would no longer be a failed magazine editor. I would be a novelist. Like so many aspiring authors before me, I mentally rehearsed how nice it would be to describe my career to impressed people at dinner parties.

Listen carefully. Can you hear that noise? It is the sound of the gods laughing in mockery.

I was filled with fresh hope and purpose. I cleared my desk at home. I bought a Moleskine notebook, and laid out 5×7” index cards for sketching out scenes and chapters. Then I sat down in my battered Herman Miller chair, opened my laptop and stared at the blinking cursor.

My first job was to create the central character. To make use of my anecdotes, I figured that this should be a magazine editor. But even though I was spinning painful memories into positivity, my ego wasn’t inflated enough to cast myself as the hero. So I came up with a different plan: I made the editor a villain. But I went a little easy on him: more of a semi-forgivable tragi-comic villain.

Like me, he would be the editor of a famous style and fashion magazine that was threatened with closure. Unlike me, he would settle on a way of saving his magazine: he would put A-list celebrities on the cover, and then, just as the issue hit the newsstands, he would assassinate the celebrity. Boom! The surge in public interest would lead to sales, and his magazine would get a reprieve. But he would have to keep murdering more celebrities to sustain this success, and this would lead to problems.

The book would be a celebrity murder thriller. A cross between US Weekly and Day Of The Jackal. Its title was Don’t Hate The Player, Hate The Game. This was a Will Smith line from the movie Bad Boys II, but it also contained my core belief: the world of celebrity was mad, and if someone wanted to shoot all the famous people, maybe they weren’t all bad.

With all these essential elements in place, I began daydreaming about how much money I might receive for the movie rights. I pictured myself living in a house on Malibu beach, with a nice tan and perfect LA teeth.

Viewed with hindsight, what I needed was a vacation, and probably some therapy. But at the time, I believed that writing about celebrity assassination would be a form of alchemy: I would transform my failure into shiny fictional gold.

The opening chapter came easily. I described a fashion industry party I had attended in New York’s Meatpacking district. It had been to celebrate the opening of a Stella McCartney store, and a white canvas atrium had been built that protruded into the cobbled street, complete with halogen spotlights and palm trees. I wrote about the caterers arriving with their trays of fois gras mini-hamburgers, and the paparazzi assembling behind the crowd control barriers. The only fictional part came at the end, when Madonna arrived in a white dress, posed for the cameras, and was shot through the head.

I read this chapter to some friends and they professed to like it. Particularly the part where the body in the bloodstained dress was described as melting into the red carpet. Then I read it to some strangers at a book reading and they applauded. But I tried to keep my feet on the ground: I knew that I was only experienced as a journalist. If I was to succeed as a novelist, I needed to learn about dramatic writing. So I bought a book called How To Write A Damn Good Novel.

Despite the title, this proved surprisingly informative. However, it did make me worry that my novel was not Damn Good. My central character was a lunatic. Although the idea of a celebrity-murdering magazine editor might be interesting in an ironic way, most novels work by having the reader follow a character that they care about. My murderous alter-ego came up with interesting methods of celebrity assassination, such as the exploding Diptych candle he smuggled into Angelina Jolie’s Oscars goodie bag. But would anyone care about this psycho enough to plough through several hundred pages?

I did some research, and came across a New Yorker article about an aspiring actress, and the pain and disappointment she endured while auditioning. The story was a moving contrast to the cartoonish fantasy that was painted in the celebrity weeklies. I decided that a struggling actress could be my sympathetic central character: she would be a lovable goofball living in Los Angeles, failing as an actress and making ends meet as a dogwalker. Through a series of unlikely events, she would end up famous. And then find herself in the crosshairs of the assassinating psycho magazine editor. Oh, and he will also have fallen in love with her. Because tragi-comedy-thriller was not enough of a mash-up. I needed romance too.

As I read more of How To Write A Damn Good Novel, I learned about the importance of conflict. I had assumed that my best celebrity anecdotes would make for rip-roaring entertainment. However, my manual informed me that this was mere window dressing: the reader would be gripped when the central character faces conflict. I had to give my aspiring starlet strong desires, and then erect barriers between her and her goals.

Around this time, I went for a drink with my former boss, a grizzled media veteran with a career that spanned magazines, TV and books. As we settled into a shadowy corner of Blacks club in Soho, he asked me what I was up to. I told him about my novel. I still enjoyed talking about the celebrity-murdering premise, but felt on shakier ground when I described my female character. He stared into his Pinot Noir before replying. I suspected that he’d seen many journalists drifting like moths towards the flickering flame of novel-writing.

“I only have one piece of advice for aspiring novelists,” he replied. “Success is achieved through the daily application of buttocks to chair leather.”

I decided that he was right. I should stop meeting friends in bars and instead redouble my efforts at home. The following morning, I applied my buttocks to my chair before dawn. While birds stirred in the trees outside my window, I sat at my desk with a mug of black coffee, tried to ignore the weight of my expectations on my shoulders, and wrote about Madonna’s funeral. It took place on a Malibu cliff-top and involved the release of ten thousand butterflies. These were caught in the updraft from news channel helicopters, chopped up in the rotor blades, and then rained back down on the guests as insect confetti.

The thing that I found hardest was creating believable characters. I compensated by adding more plot. Since I was writing about Hollywood, I needed a movie for my actress to star in. Much like the book it appeared in, this was an unlikely combo of thriller and black comedy. It featured terrorists slipping botulism into the world’s supplies of aviation fuel, turning every airliner into a crop-duster of plague. The only survivors were people who’d had Botox injections. The movie was called Spore. Its tagline was “Everyone’s dead, but nobody’s frowning.”

But as I built plots within plots, my characters became ever more lifeless and doll-like. I could make them do weird stuff, but when I was done, they just went back in their boxes, completely inert.

Seeking advice, I joined a writers group. I couldn’t find a group writing celebrity murder mysteries, but I did end up with some very nice ladies who were working on short fiction. They had all studied creative writing, and lived in a post-modern literary world which had long ago shed the pedestrian concerns of character and conflict. It didn’t help me push things forward, but we did have many delightful evenings drinking white wine and admiring each others’ metaphors. If I suggested that a cluster of paparazzi cameras looked like a multi-lensed insect eye, the ladies would nod with approval.

After a few more months, I had an ending to my story: the magazine editor would have my Dogwalker Actress in his sights as she arrived at the premiere of Spore. But, at the last minute, he would feel a pang of conscience, lower his aim and shoot her through the leg. She would attain instant fame as the lone survivor, while he would be shredded by a hail of police bullets.

I felt that there was a pleasing symmetry with the opening. Now I just needed to complete some chapters in the middle, and send the manuscript to a publisher. But I was about to encounter another flaw in my scheme.

By this time, I had a day job working as a designer, and was focusing on toys and other kid-focused products. My partner was a researcher with a PhD in child psychology. His doctorate had focused on imaginary friends, and I teased him about this so much that he forced me to read a book about it. This book explained the concept of the “paracosm”: a fictional world that the child dreams up, fills with people and sustains within their imagination. The book argued that the ability to create a paracosm was a sign of a healthy creative mind. It also talked about novels: when authors dreamed up worlds and characters, they were creating paracosms. As were the readers, when they became “lost” in a book

I found this concept fascinating. But it made me see a problem: my original idea was to feature the celebrity anecdotes I’d collected at The Face. But something about using real celebrities in a fake world felt jarring. The paracosm theory explained this: when reading fiction, the reader was creating an imaginary world and bringing the characters to life. But the reader already had a mental construction of celebrities, from all the celebrity magazines and TV they consumed. If I asked the reader to dream up a fictional universe, and then had Madonna walk into it, I was crashing two paracosms together.

Suddenly it was clear why there were so few novels contain real, living celebrities: nobody wants their brains messed with while they’re reading on a beach. This might also be the reason why the genre-mashing approach of fan fiction has never grown out of its amateur niche on the internet. There was something fundamentally psychologically wrong with my approach.

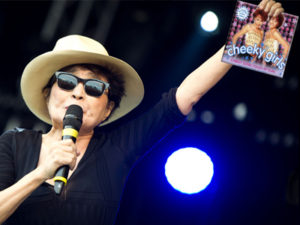

But by now I’d spent more than a year getting up in the morning at 5am and sitting at my desk. I couldn’t walk away from all that pre-dawn pain. So I started replacing my celebrities with fictional alternatives. Madonna became Magdalena. Tom Cruise became Steven Taurus. The producer Jerry Bruckheimer became Rikki Oppenheimer. As I re-read the chapters, they were less jarring, but they were also less interesting. I now needed to invent a compelling backstory for every character: the fake celebrities would need fake bios. My “celebrity short-cut” had led me into a swamp.

I kept returning to the writers’ group. My companions were failing too, but in different ways: they were so well-informed about literary conventions that they were incapable of writing something with a plot. We all kept reassuring each other that we were doing great, but we were all equally lost.

On some level, I knew that my novel was doomed, but I couldn’t admit it to myself. Finally, mercifully, someone applied a pin to my balloon full of dreams. I met a HarperCollins publishing executive, and mentioned my project. She asked if one of her editors could look at my manuscript. When the report came back, the opening words were “I really wanted to like this…”

I re-read those first six words. I didn’t need to look further: the past tense of “wanted” was enough to confirm what I had already come to believe: my novel was destined for failure. Madonna would never be assassinated on my red carpet. Instead it was my dreams of career alchemy that had been killed.

The truest thing I’ve ever heard about novel-writing is that it’s like building a house out of raisins. Looking back, my biggest problem was that I was trying to be a smart-ass. I was trying to deliver ironic black humor while making people care. I wanted commercial success while exorcising my demons. And I was trying to short-cut the whole novel-writing process by collaging together celebrity anecdotes.

Graham Greene wrote: “With a novel, which takes perhaps years to write, the author is not the same man he was at the end of the book as he was at the beginning.”

I was not the same afterwards. I had to admit defeat to friends and family. I had to admit that my celebrity murder fiction would never be a movie and I would never get the awesome beach house in Malibu. But it wasn’t all bad: I learned a lot about storytelling, drama and character.

I learned that to write fiction is to dream up a paracosm, and that my characters should be like imaginary friends, alive in my head with their hopes and struggles. I also learned that it is foolish to put Madonna or Tom Cruise in your novel.

I tried to build a house, and all I created was a giant pile of raisins. But I’m wiser for the experience. And maybe, one day, I’ll try again. Hey, maybe I could write about a failed novelist who murders everyone who doesn’t like his book? Now all I need is a few good sub-plots…