Weird though it seems, Sam Smith’s song – Writing’s On The Wall – has become the first Bond theme ever to top the charts. How has Sam Smith managed it? We stripped all twenty-three Bond songs down to their bare essentials to see if there was any explanation for it. Any explanation at all.

Tuneraker

Shirley Bassey couldn’t do it. Paul McCartney couldn’t do it. Louis Armstrong, Tina Turner, Tom Jones, Madonna – none of them could do it.

Award-winning composers and lyricists tried and failed. Multi-platinum artists with record-breaking chart-toppers couldn’t crack it. Even Adele – who walked away with an Oscar for her attempt – didn’t manage it.

And yet, somehow, Sam Smith has done it. With a song he claims took twenty minutes to write, Sam Smith has gone and taken a Bond theme to number one.

How did he do it? A world-weary cynic will tell you that this is because it’s much easier to get a number one record in 2015 than it ever was in 1965. The charts aren’t competitive anymore. Anyone can get a number one now. You can sell more records going door to door. Et cetera, et cetera.

There’s some evidence that would appear to bear that theory out. If you look at the charting history of Bond themes over time, you can see there are far fewer flops these days. In the last 25 years, nothing has charted below Number 20 even though the songs themselves are rarely considered classics.

True though it may well be, it’s a fairly dull reason to give – and it doesn’t go any way to explaining why both Adele’s Skyfall and Duran Duran’s A View To A Kill both stalled at number two, nearly thirty years apart, despite both songs being released at the height of the artists’ peaks.

So if the charts are so easy nowadays, why did Skyfall miss out? What is it about Writing’s On The Wall that has ‘NUMBER ONE SMASH’ written all over it? What was missing from enduring classics like Goldfinger, Nobody Does It Better and We Have All The Time In The World?

The only way to know for sure is to pull them all apart into their constituent bits and pieces and go pattern-searching.

Timing

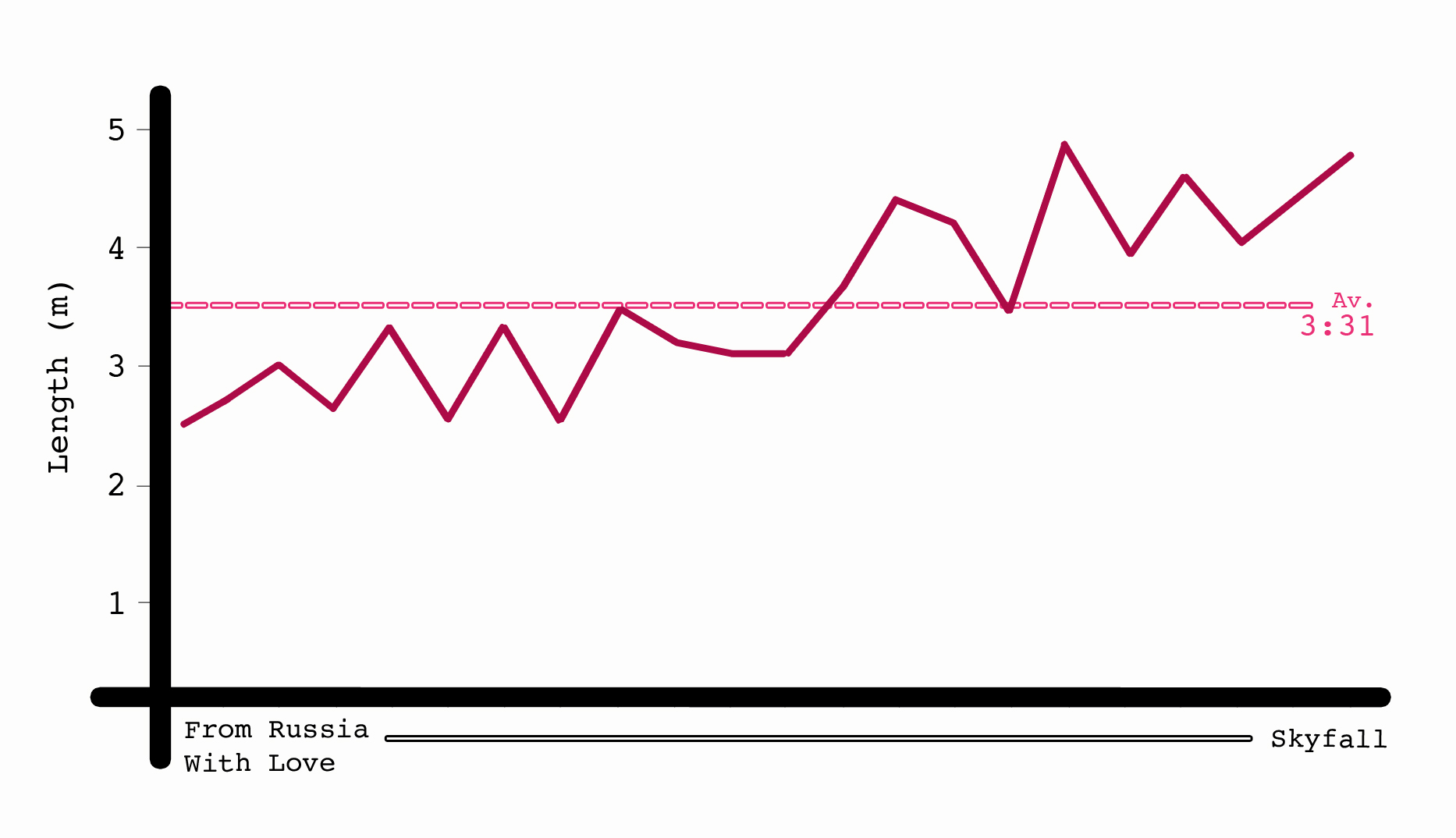

Let’s start with something very simple – the timing. Can we ascertain how long an ideal Bond theme should be?

As you can see, the general trend shows that Bond themes have been gradually increasing in length over the last 50 years.

Before Duran Duran’s A View To A Kill in 1985, not a single one of them was longer than three and a half minutes. Then a-ha breached the four minute mark with The Living Daylights in 1987 and few themes since have dipped back down below 3:30.

This marked a watershed moment. For not only was this the point where Bond themes began to consistently break the Top Twenty, it was also the point where Bond themes began to be routinely chopped up in order to fit the films’ opening credits sequence.

Take The Living Daylights. The single version of The Living Daylights is 4:04. Obviously 4:04 is far too long to have an audience just sitting and reading the names of executive producers, production supervisors and second unit directors (no matter how many sexy silhouettes you have shimmying about behind them) so it got trimmed down to 2:49. More than a minute of Morten Harket left on the cutting room floor.

A savage cut, but one that worked. The movie was a commercial success, a-ha got themselves a Top Five hit and pop fans still got themselves a decent length single for their money.

Every Bond song since has followed this pattern. It has been written overlong and then left at the mercy of editors, who unceremoniously lop out a chunk of it to fit the films’ needs. (Except for Goldeneye – because Bono and The Edge appear to be the only modern pop composers who know how to work to a commission).

Will the same thing happen to Sam Smith’s song? Undoubtedly. Writing’s On The Wall is one of the longest Bond themes ever written – third only to Sheryl Crow’s Tomorrow Never Dies (4:57) and Adele’s Skyfall (4:46). So even though he is in keeping with the current best practice, Sam can still expect to see a good sixty seconds of his song get snipped out of the opening sequence.

That’s no bad thing though, because long Bond singles seem to sell best. Four of the five biggest Bond hits to date (A View To A Kill, Die Another Day, Skyfall and Writing’s On The Wall) are all longer than 3:30; and the only three which failed to chart (The Man With A Golden Gun, Moonraker and All Time High) are all shorter.

There’s another reason that Writing’s On The Wall song goes on for so long though – and it’s this…

Tempo

With the exception of the piano-led intro to Live And Let Die, Writing’s On The Wall is the slowest-paced piece of Bond music to date. But where Live And Let Die ramps things up after 45 seconds and bursts into the franchise’s fastest riff, Sam Smith has decided to keep plodding along at a sluggish 66bpm for the full four and a half minutes.

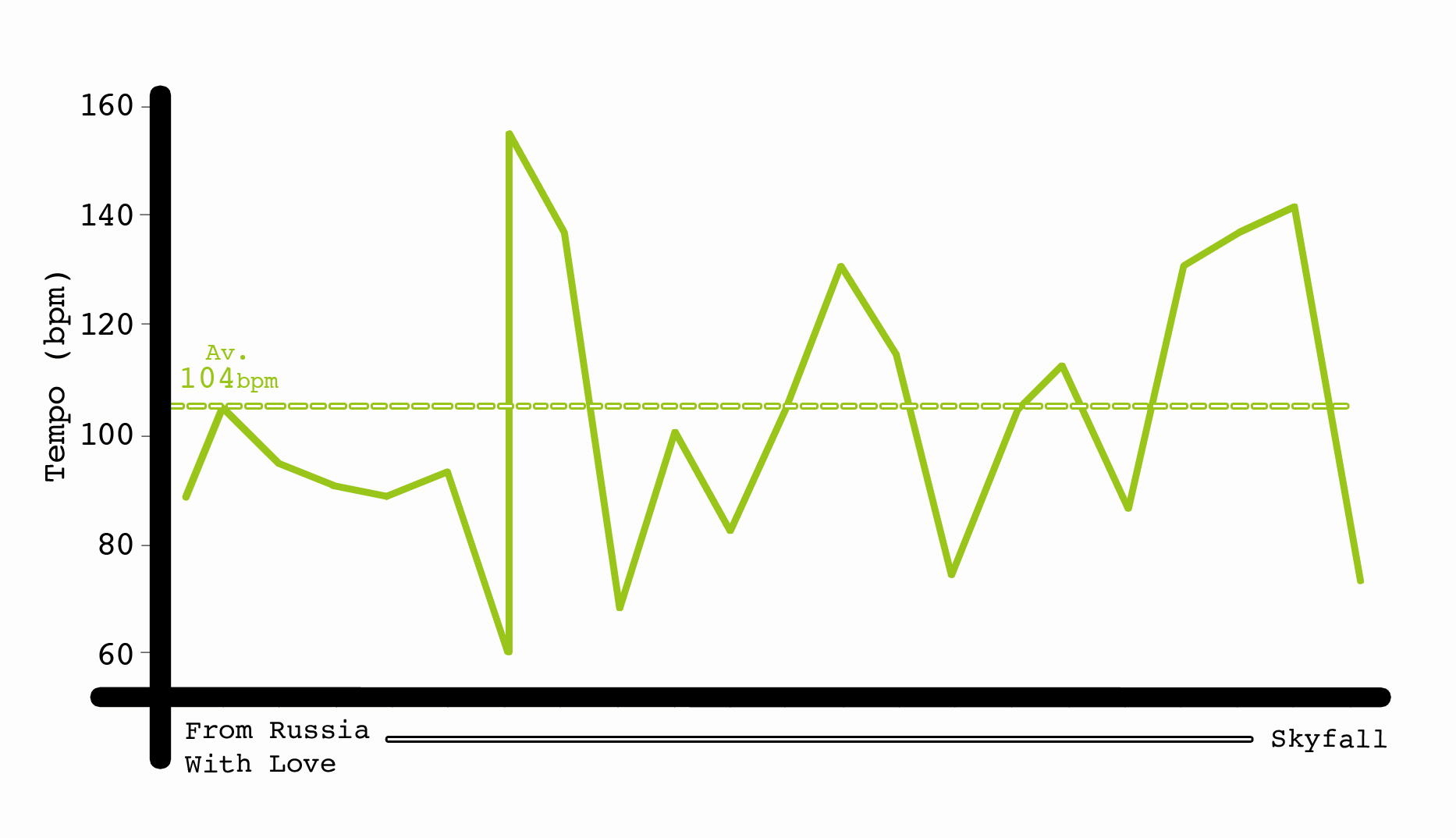

How does that tempo compare to the rest of the canon?

All in all, the average tempo of a Bond song is 104bpm. By strange coincidence that is also the exact same tempo marking of Goldfinger (which is often polled as being the definitive, quintessential Bond theme) – but we are working with a wide range here.

There has always been a mix of speeds throughout the series. You have the slower, tender, more reflective numbers like We Have All The Time In The World, For Your Eyes Only and Moonraker. Then there are the faster, punchy, full throttle numbers like The Man With A Golden Gun, A View To A Kill and Another Way To Die.

Writing’s On The Wall is, without question, the slowest of the lot. That’s true not only of the physical tempo, but the general feel of it too.

It stands to reason that it would be. Sam Smith has the air of a moper. A Facebook sulker. A millennial Morrissey. The sort of nightmare boyfriend who drags you out of parties to complain about the way you’re ignoring him. A solemn, overly-earnest ballad is exactly his forte.

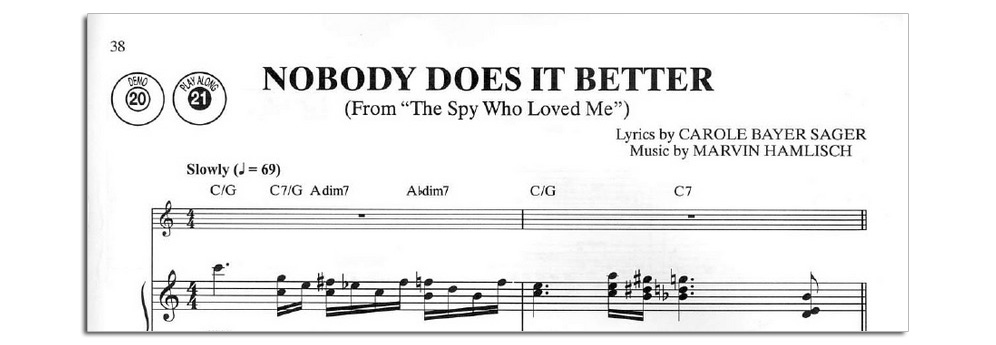

But compare him to Carly Simon. Nobody Does It Better is only actually a few beats per minute quicker than Writing’s On The Wall but Nobody Does it Better doesn’t seem to be anywhere near as slow. Why is that? There’s a few reasons.

Partly it’s the choice of percussion. Carly Simon uses a full drum kit in Nobody Does It Better with the hi-hat marking out an 8-beat rhythm (the cymbal being played twice per beat); whereas Sam Smith’s primary percussion is the piano, which either marks out a 4-beat rhythm (slower, one chord per beat) or, in places, a 2-beat rhythm (slower still, one chord every two beats).

Carly Simon also changes chord twice in each bar – a trick which gives the song the drive of something twice the speed. Sam Smith, on the other hand, relies on a string-heavy orchestra which produces slow, swelling, drawn-out chords – many of which last the full length of the bar. The huge gravity of that sound, combined with the slow count, makes for an incredibly lumbering piece.

However, this is all to Sam’s credit – as it seems to be that fast or slow are the way to go. Hitting the mid-tempo middle ground of 100bpm seems to be pretty deadly for Bond. Two of the non-charters (Moonraker and All Time High) were paced at 101bpm and 105bpm; while none of Goldfinger (104bpm), Thunderball (96bpm) or Diamonds Are Forever (96bpm) broke the Top Twenty.

–

A SLIGHT SIDE NOTE: For a character that trades so heavily in innuendo, there aren’t a great number of a sex jokes hidden inside the soundtracks of James Bond. One of the tracks on the A View To A Kill OST has the title Snow Job, but a slightly more subtle gag? The tempo marking for Nobody Does It Better.

Key

Let’s delve a little deeper into the technical side of things. What keys are most favoured by Bond theme composers?

The three most popular keys for a Bond theme to be recorded in are E, G and B. This is not really a surprise. The notes E, G and B – when played together – make up an E minor chord, and E minor is the key of Monty Norman’s original James Bond Theme (the classic surf rock riff from the gun barrel sequence). It is therefore relatively easy to segue from the James Bond theme into a song recorded in E, G or B – so it makes sense that these keys would appear more frequently than others.

Writing’s On The Wall is written and recorded in F minor. The other two songs to be recorded in F are Nobody Does It Better (which reached No.7) and Garbage’s The World Is Not Enough (which reached No.11).

Not a key that has seen dizzying success previously, but one that shows some consistency (unlike E, G and B, which have all turned out some absolute turkeys).

Key Changes

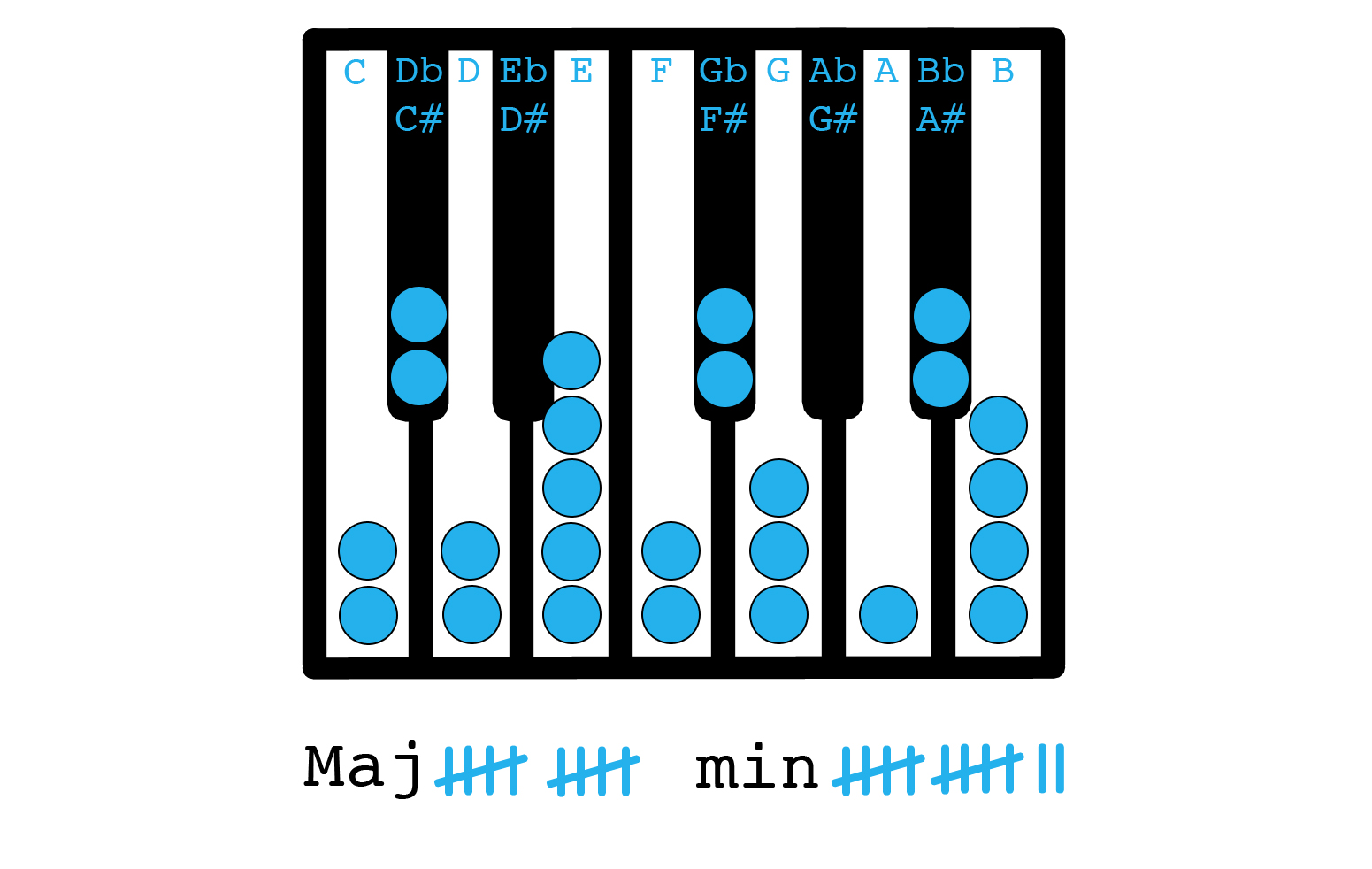

You may have noticed that there were more than 22 dots on that little keyboard graphic above. If so, well spotted. Not much gets past you, eh? Well, those extra dots were added to account for the songs which involve some very significant key changes.

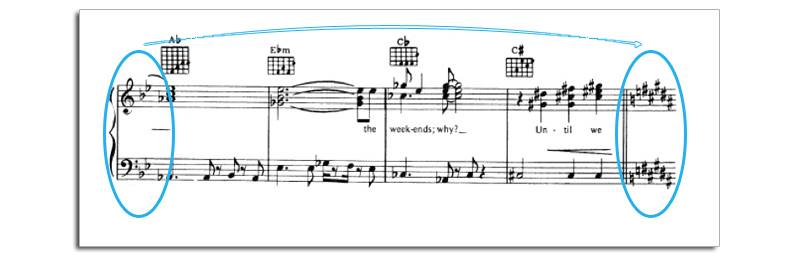

The key change is a slightly complicated topic to discuss with film soundtracks, because soundtrack composers often have a different relationship to key than a pop composer does.

Take songs like Goldfinger or You Only Live Twice – both of which were written by the series’ most celebrated soundtrack composer, John Barry. Both of these songs play fast and loose with their keys, often making unusual and arresting chord changes, or incorporating particular notes that aren’t a usual part of the established key’s scale. While the inclusion of these sorts of notes and chords indicates that the song may technically have changed key, they are only temporary modulations. The music will very quickly finds its way back to the original key. In these instances, such modulations can be written out easily on a score by altering a few notes, on a note-by-note basis.

When it’s out-and-out pop acts writing the theme though, the keys tend to be slightly more fixed. The chord changes they use are more traditional and predictable. The melodies are much less adventurous. If they ever do change key (and a handful of times they do) they tend to change key for a significant length of time. Enough to make it worthwhile changing the score’s key signature.

There are four songs that involve such significant key changes: Live And Let Die, All Time High, A View To A Kill and – the only one to employ the classic Westlife-standing-up-from-their-stool, once-more-with-feeling key change – Licence To Kill.

Generally though, they’re best avoided – as Sam Smith seems to have realised.

Tonality

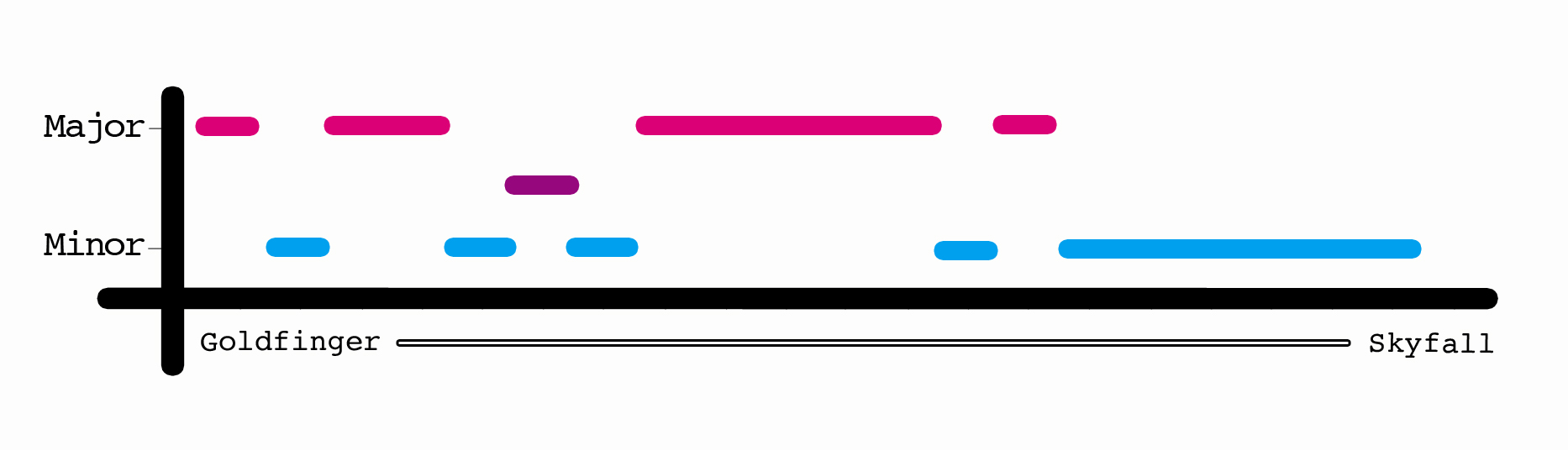

Like much of the rest of modern cinema, the Bond franchise has recently taken a turn for the gritty. But has Daniel Craig’s darker interpretation of Bond been reflected in the composition choices? Are the Bond themes predominantly major or minor?

The prevailing darkness of Bond themes actually appears to have predated Daniel Craig. Minor keys have practically become de rigueur for Bond since the days of Pierce Brosnan – as every theme for the last twenty five years (from Goldeneye to the present day) has been in a minor key. As all of them have been at least a Top Twenty hit, it looks like minor keys are the safest bet and – given Hollywood’s current obsession with making every action movie dystopian, drab and colourless – it looks like this isn’t going to change any time soon.

(FYI: That purple one which straddles major and minor is Live And Let Die. Its sung sections are in major keys, while the main instrumental riff – which makes up about half of the song’s running time – is in the parallel minor key.)

Chords

Never has a musical motif been so closely identified with one single character as it has with James Bond. Sure, you could make a good case for Jaws (the shark; not the henchman) and those low, ominous semitones. Norman Bates and that little stabby sequence from Psycho have become a part of the popular culture too. But with their various compositions over the years, Monty Norman and John Barry have essentially ring-fenced a handful of musical phrases and chords which now – whenever they’re used, in any context – immediately put people in mind of Bond.

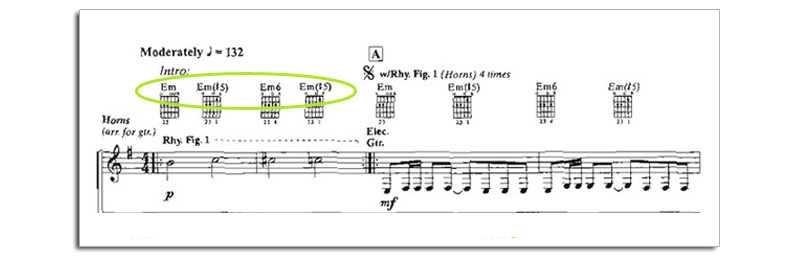

The most recognisable phrase is the rising and falling chord sequence in the James Bond Theme. It’s that shuffling, creeping bit where an E minor chord is followed by an E minor with a sharpened fifth, then up to an E minor sixth, then back down – which gets repeated over and over as the guitar jangles over the top, followed by the punchy brass, or swirling synths.

Not only is this pattern used in all the films’ scores, the same progression crops up in the themes a lot too. The easiest place to spot it is in Goldfinger, under Shirley Bassey as she sings “He loves gooooooold / He loves only gooooooold” – but it makes cameos in Thunderball, Goldeneye, The World Is Not Enough, Skyfall and others too.

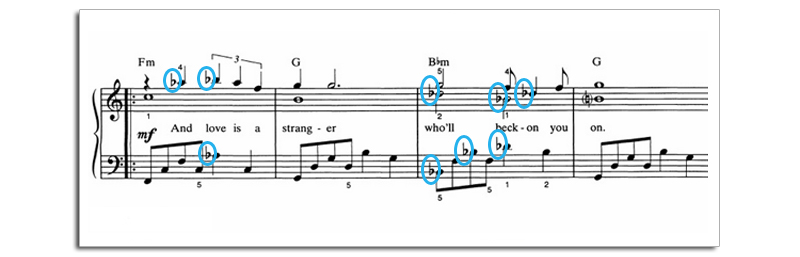

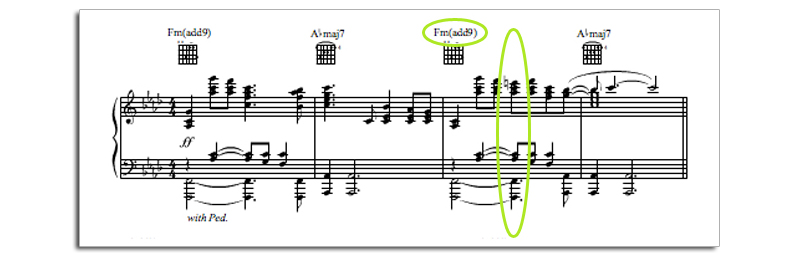

Though Writing’s On The Wall doesn’t use this particular progression, it does use one of the other well-known tricks in the James Bond bag: the infamous spy chord.

The technical name for the chord is the ‘Minor Major Ninth’ – often styled ‘m(M9)’ – and it’s the one that usually punctuates the end of the song, ringing out on a guitar with that slightly spooky, dissonant sound. Sam Smith doesn’t use it excessively (nor exactly, for that matter) but it does make an incredibly brief passing appearance in his introduction.

See that top note in the ringed chord? The one with the ♮next to it? That is an E natural, which is the Major 7th in the key of F. That’s the one which will fleetingly change that Fm(add9) you can see to an Fm(M7) giving it that distinctive Bond flavour.

That tiny little note is pretty much all that separates the song from being the kind of ballad that finishes 18th in the Eurovision, and a successful Bond theme. Strange, isn’t it?

Last Note

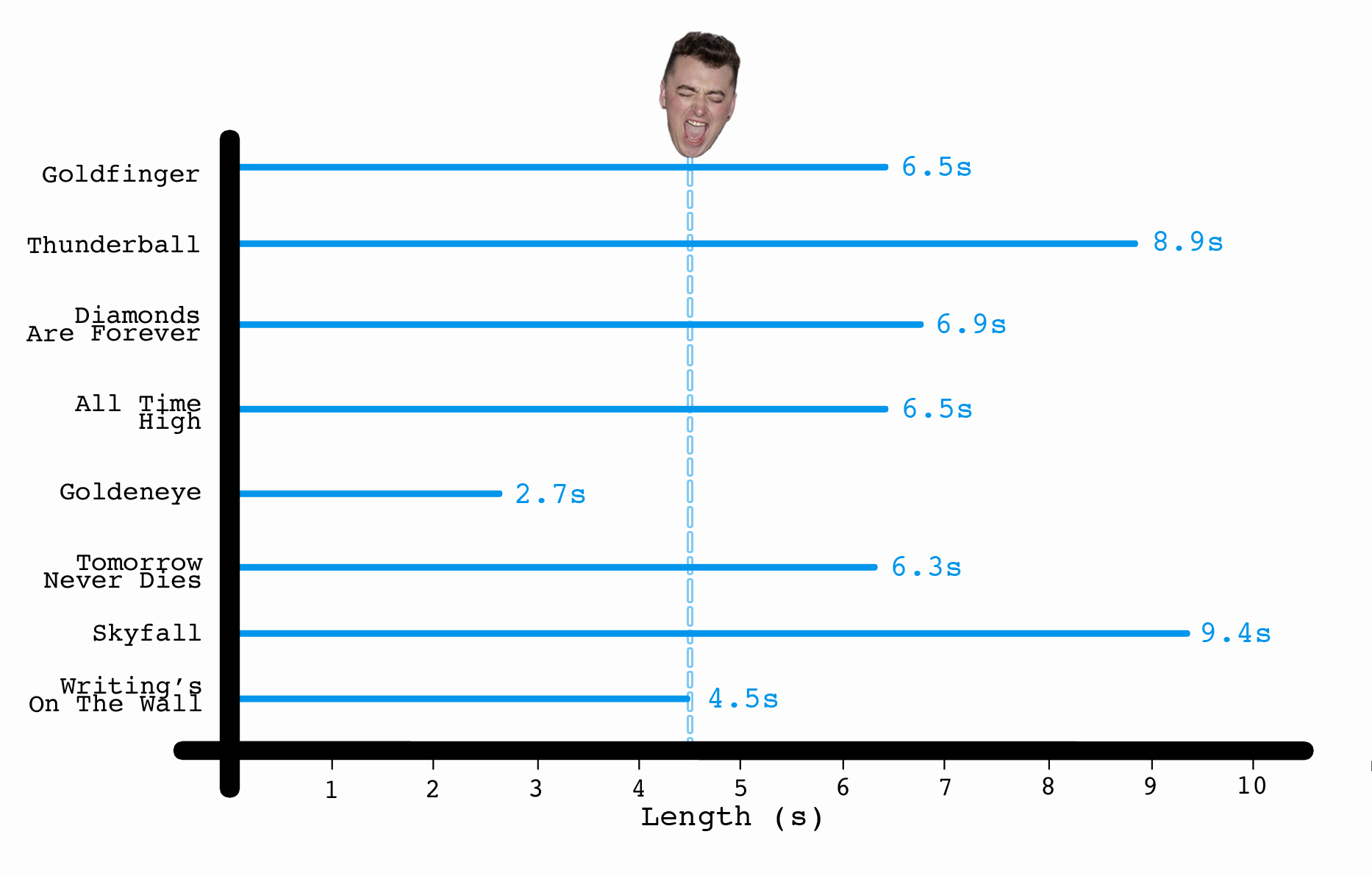

And so we reach the end. The cherry on top. The final note. Shirley Bassey famously had to take off her bra to hit her final note in Goldfinger. Tom Jones claims he passed out when he sang his on Thunderball. Yes, an impressive belted note is a staple of the Bond theme. So how does Sam stack up?

The answer? Not so well. Despite giving it a go and trying to hold out for an impressive note he doesn’t even manage to beat out some of the notes that the often-ridiculed Sheryl Crow managed. (Although, admittedly, she does sound a lot less comfortable doing them.)

However, as much as we might like to think it’s an all-important ingredient, the songs with big belted notes have actually been some of the least commercially successful. Goldfinger, Thunderball and Diamonds Are Forever all failed to make the top twenty; All Time High only reached number 75 in the charts. Adele is the only one who makes a convincing case for long notes to be a good move for a chart-topping Bond theme, and hers only came out a few years ago.

Meaning that Sam Smith was probably right to cut out when he did.

In Conclusion

So how many feet did Sam Smith put wrong? Given the lukewarm critical reception that the song has received we initially thought the answer would be ‘loads’. Having pulled everything apart though, he actually seems to have done everything by the book.

Above 3:30? Check.

Dramatic tempo? Check.

Minor key? Check.

No key change? Check.

Inclusion of a James Bond motif? Check.

Exclusion of the actual James Bond Theme? Check.

It couldn’t have been more precisely engineered to be successful, yet critics been pretty vocal in their distaste for it. It’s everything we want from a Bond theme, and everyone seems to have bought it, yet nobody seems to be happy. But what were the producers to do? We say we want big, bombastic brass and slinky guitars, and powerful vocals, but then we go and make Skyfall – the bleakest, greyest movie of the franchise – the most successful. We’ve practically begged for Bond to become a washed-out, fallible, guilt-racked antihero, then we get all disappointed when they let Sam Smith whinny all over the opening credits?

He might not have given us the Bond theme we want, but he’s given us the Bond theme we deserve.