Once a reliable refuge from the miseries of the modern world, the pop charts are becoming every bit as grim as real life. 2017 in particular has really seen things take a turn for the maudlin – but why is it happening? Why are we so obsessed with sad sounding songs at the moment?

Whine Of The Times

It’s been a bleak old year, hasn’t it? Politics is in turmoil, the economy is a pile of old shit, and the Grim Reaper is still indiscriminately swinging his scythe around without a care in the world.

It’s been a bleak old year, hasn’t it? Politics is in turmoil, the economy is a pile of old shit, and the Grim Reaper is still indiscriminately swinging his scythe around without a care in the world.

And now even pop music – the one thing that could usually be relied upon to provide a little light relief on this angry, dying planet – has gone and got all sad and depressing on us too.

Perhaps we like to wallow in misery at times of great unrest. Perhaps the music being made simply reflects the mood of the moment. Maybe you think we’re just being a bunch of miserable old gits whinging about what kids these days are listening to, but there’s a little more too it than that. 2017 has seen a very strange shift in our listening habits. Music is getting measurably more miserable – and we’re not entirely sure why.

We might as well have a punt at trying to figure it out though…

Stuck On Repeat

Ever since things started going off the rails back in 2016, it appears the UK has been acting like a recently dumped teenager: locking ourselves in our room and listening to the same songs over and over and over again.

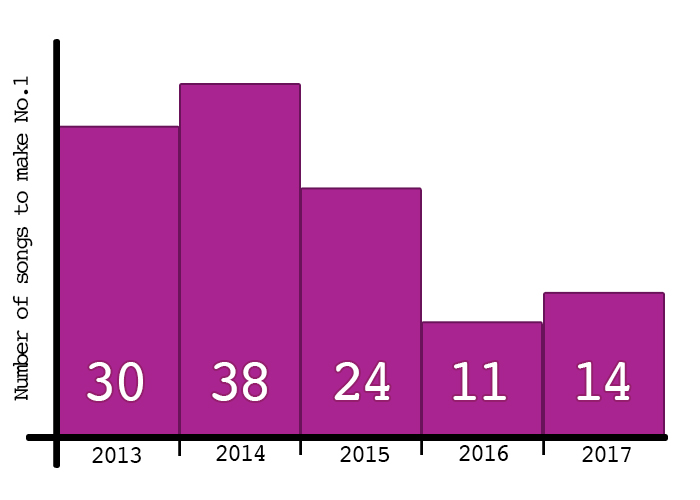

A quick scan down the the charts for the last five years shows that fewer songs have been making it to number one. There were just 14 number ones in 2017; less than half the number there were in 2013.

Part of the reason for this is that, increasingly, hit singles are having Bryan Adams and Wet Wet Wet-style runs at the top.

Drake’s One Dance had 15 consecutive weeks at number one from April to August of 2016. Ed Sheeran’s Shape Of You did 14 weeks from January this year. Despacito racked up 11 weeks over the summer. With so many of these singles camping out in the top spot for such long stretches, the chances for other songs to break through are limited.

The way in which we consume music these days is largely to blame for that. When the charts were dictated by sales and sales alone, any one individual’s influence on that week’s chart was limited. You could buy a song and help to boost its chart position – but unless you had the budget to buy multiple copies over multiple weeks, you only had that one shot.

However, now that streaming figures are included in calculating chart positions, that’s all changed. By continuing to stream their favourite songs week after week, punters are now creating a sort of positive reinforcement cycle that’s quite tricky to break.

Being popular gets you a good place on a Spotify playlist; getting a good place on a Spotify playlist gets you more plays. The more plays you get on Spotify, the better your chart position. The better your chart position, the better your placement on Spotify playlists. The more you get heard, the more popular you become. The more popular you become, the more you get heard.

This is not a particularly groundbreaking observation. People have been talking about this quirk of the new chart calculations for years now. What is interesting about this run of long-standing number ones though is that something else significant seems to have changed since the days of Everything I Do and Love Is All Around.

Specifically: the key that the songs are in.

Setting The Tone

This is something we’ve harped on about for years (particularly in relation to Eurovision) so our apologies if you’re bored of hearing about it, but 2017 has pretty much borne out our theory on minor keys.

To quickly explain what we mean by ‘minor’ and ‘major’ keys:

In general, major keys create music which is considered to be bright, joyful and happy sounding. (A classic example: the wedding march.)

Conversely, music that’s written in a minor key is considered to be mournful, moody and sad sounding. (A classic example: the funeral march.)

Broadly speaking, you can split almost all of Western music into one of those two camps – stuff that’s in a major key, and stuff that’s in a minor key. The major=happy and minor=sad dichotomy is not an absolutely hard and fast one, but it’s a pretty decent rule of thumb.

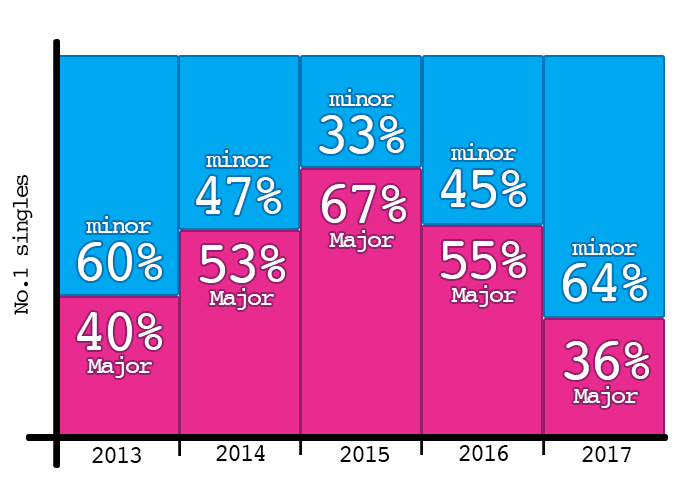

That being so, how have major and minor keys fared at the top of the charts for the last five years?

Nearly two thirds of the songs that have made it to number one this year have been in minor keys – which is the highest concentration we’ve seen for ages.

Post Malone’s Rock Star, Sam Smith’s Too Good At Goodbyes, Havana by Camila Cabello. All in minor keys, all at number one for multiple weeks.

Compare that with the major key hits of the year. Harry Styles’ Sign Of The Times, Clean Bandit’s Symphony, I’m The One by DJ Khaled. All in major keys, only at number one for a single week.

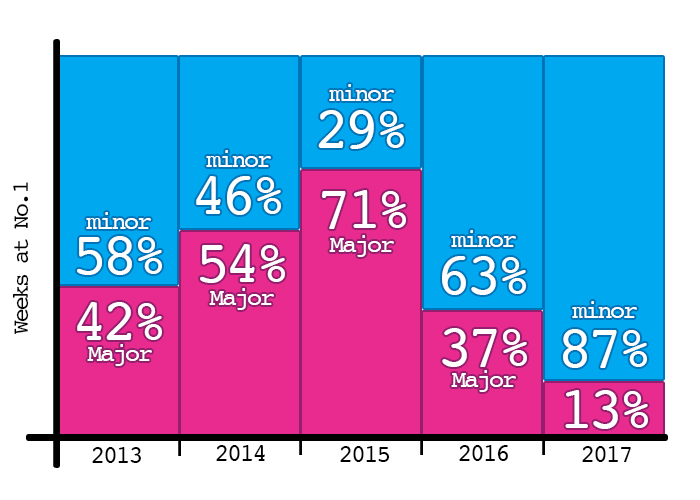

So rather than looking at the number of No.1s that were major/minor, perhaps it makes more sense to look at how the year was split in terms of weeks that had a minor key number one versus weeks that had a major key number one.

If we conservatively presume that Ed Sheeran is going to clinch the Christmas number one with one of his many versions of Perfect (although Eminem’s River is nipping at its heels) then just six weeks of 2017 so far will have had a major key number one – whereas forty-five weeks will have had a minor one.

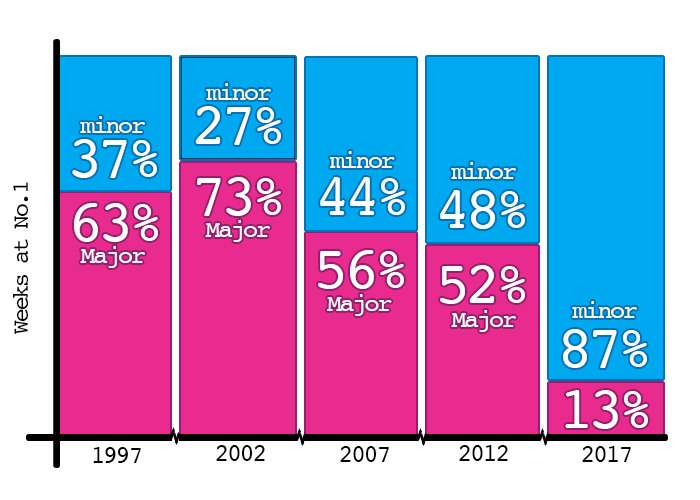

We aren’t just cherry-picking these years either. If you look back over the last twenty years (as we have, at five year intervals) then you see that this is a uniquely miserable set of affairs.

Keys are a very important part of the picture here, but they’re not the only way to make a song sound happy or sad.

Songs like Candle In The Wind or Tears In Heaven are quote-unquote sad songs, but they’re both in major keys (not unlike Harry Styles’ Sign Of The Times). On the other hand, songs like Boogie Wonderland or Don’t Stop Movin’ are big party tracks, but they’re both in minor keys.

There’s more at play than tonality alone. The speed of the song can have just as much of an effect on our mood than the key does. So how has that shaped up over 2017?

Sad Times

Tempo (the technical name for the speed of a song) is measured in beats per minute, or bpm. The higher the bpm, the faster the song. If you imagine a drummer counting in “1… 2… 3… 4…” before a song starts, that’s basically what you’re looking at.

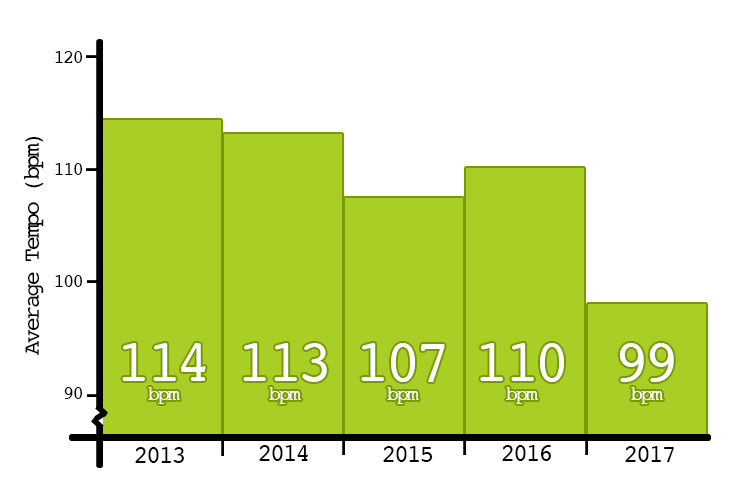

You can usually expect a healthy balance of upbeat bops and slower ballads to top the charts in any given year – but not 2017. For the first time in years, the average bpm of a number one record has slipped below 100bpm.

You know what that means? We’ve officially gone slushy.

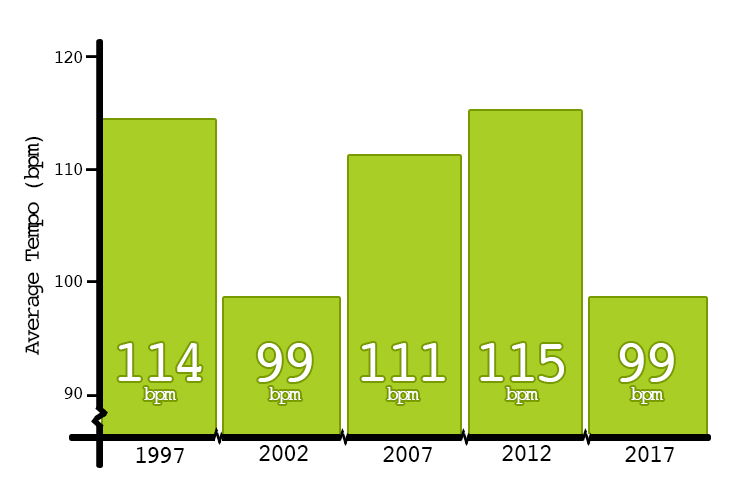

That said, a 99bpm average is not without precedent. Tracing the trend back twenty years, it’s clear that we have reached these schmaltzy lows once before in 2002.

And what sort of songs were littering up the top spot back then?

Ronan Keating’s cover of If Tomorrow Never Comes. Gareth Gates’ cover of Unchained Melody. Atomic Kitten’s cover of The Tide Is High. Blazin’ Squad’s cover of Crossroads.

Have we really not learned our lesson? Is this the world we intend to hand over to the next generation? A culture that refuses to admit it made a mistake in letting Ronan Keating get to number one? Multiple times?

Sadly, it seems not. And what’s more: things might yet be getting worse.

A Slippery Mope

A Slippery Mope

A 2012 study into the changing emotional cues of American popular music since 1950 showed, pretty conclusively, that pop music has been getting sadder and sadder as time presses on.

The researchers, Schellenberg and von Scheve, took 1,000 Top 40 songs from 25 different years across five decades and found that the later a song was recorded, the more likely it was to be in a minor key at a slower tempo.

Why might this be? A historical perspective might offer some clues.

When music was first pressed onto vinyl, the size of the record was fixed. This meant you had a definite limit to the amount of music you could physically fit on it. As early records were played at 78 revolutions per minute, that gave you enough of a groove to fit about three minutes of music on each side.

As such, there really wasn’t much time to mess around. Pop songs had to be over and done with quickly. You had a (literal) pressing deadline.

The easiest way to make sure that your verse-chorus-verse-chorus pop song fit onto a single vinyl side was to make sure that it was snappy. So you pick a high bpm. And as high bpms lent themselves to upbeat, bright and bouncy songs, it made sense to pick a major key too.

And so the three-minute pop song was created. Radio stations built their advertising schedules around them; the public consequently developed a matching attention span – and the mould for pop was set.

As the technology developed and these early constraints were lifted, musicians soon had the luxury of recording much slower, more contemplative songs. In dropping the tempo down a little, they could spread the classic verse-chorus-verse-chorus template out to four minutes. Maybe more. Singles started to get longer.

Now that we live in a digital world, where our musical delivery systems have no real physical constraints to speak of, we are totally free to be as slow and maudlin as miserable as we like. Spotify is just as happy to stream a six minute ballad than it is a three minute banger.

None of which means that we have to be sad in the modern world. Often, we aren’t. We certainly weren’t in 1997, when number one songs were 63% major and 114bpm on average. We didn’t appear to be doing too badly in 2015 either, when number one songs were 71% major and 107bpm.

But ever since Bowie died in early 2016, things have been getting steadily more bleak – both in the world at large, and in the pop charts too.

Could the two be connected?

Possibly, yes.

There has actually been an academic study done into this phenomenon. A paper published in 2009 by Terry F Pettijohn (et al) found that times of social unease, economic hardship and general doom tend to inspire songs that are longer and slower.

Which certainly squares with our current situation. Whether it’s our changing tastes, or simply what we’re being fed by depressed artists, there’s no denying that we’re being served up some pretty blue-sounding stuff at the minute.

But if the global mood is what’s behind that, it means we’re going to have to wait for the wider world to shake itself out of its current slump before the charts start getting any brighter.

So here’s to 2018. We look forward to more wallowing.